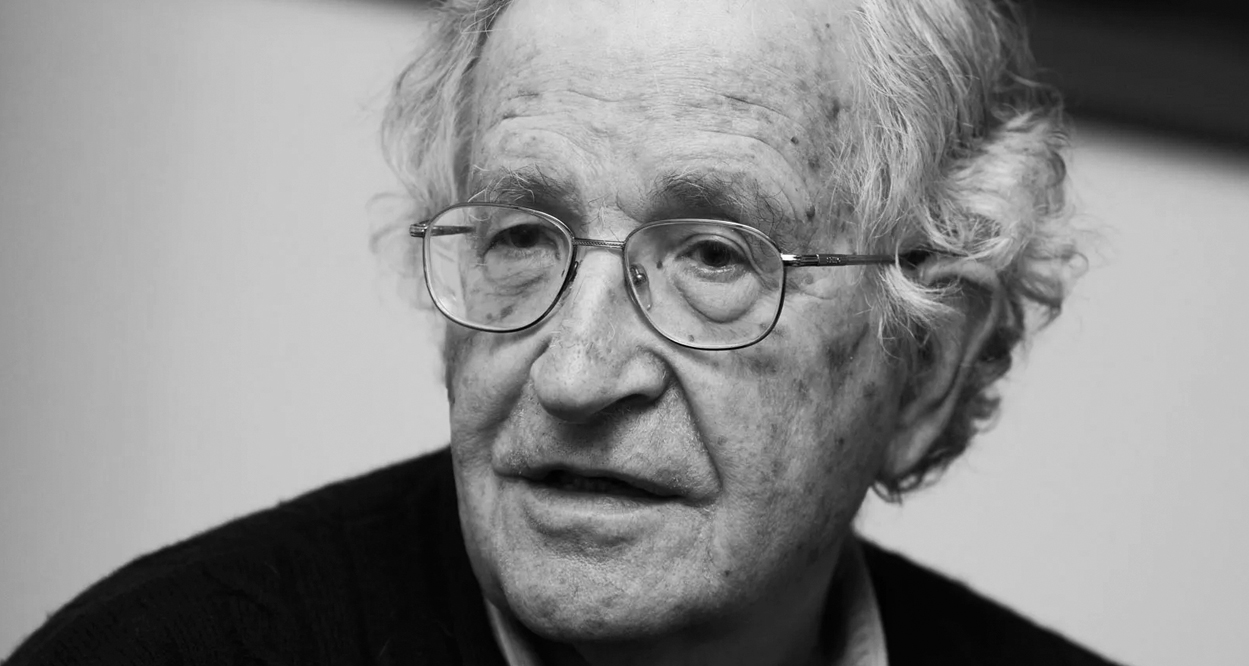

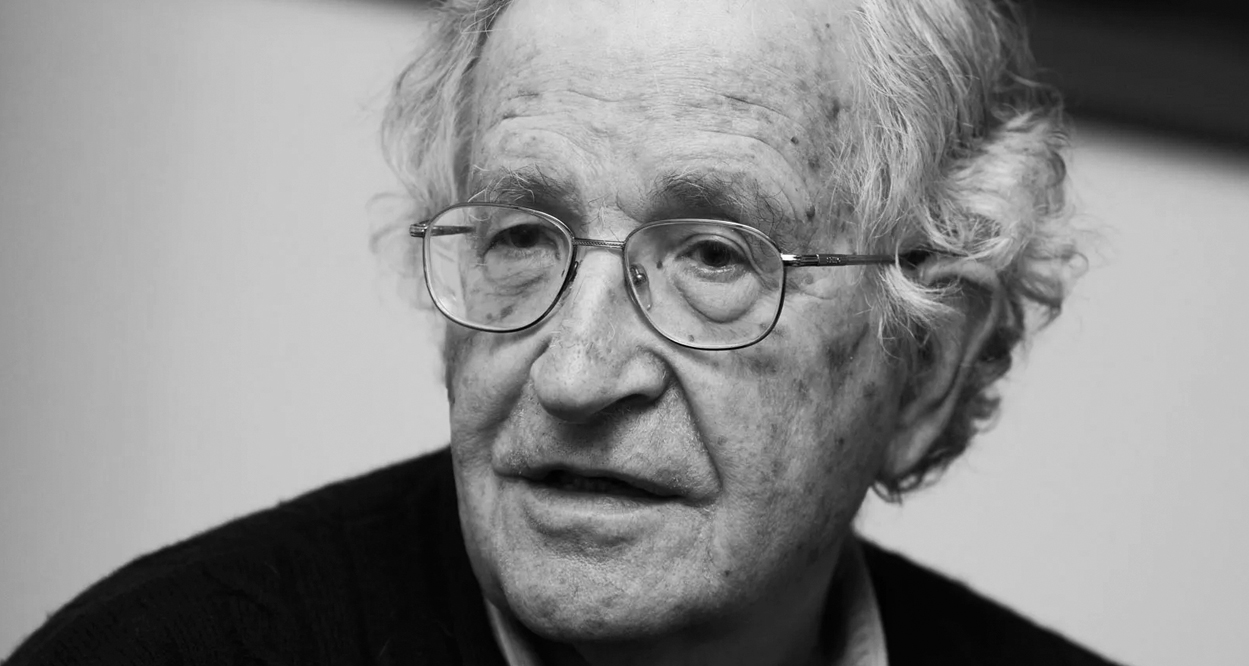

Noam Chomsky—American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. He is sometimes referred to as ‘the father of modern linguistics’ and is also a major figure in analytic philosophy, and one of the founders of the field of cognitive science. Here, he talks about the changing nature of media, journalism, politics and censorship. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #4 which focused on the theme ‘Propaganda’.

Note: This interview took place in 2007 and refers to specifics from that time.

Kevin Finn: There is a saying: ‘A little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing’.

Noam Chomsky: Would you agree with this statement? A little bit of knowledge is, almost by definition, omitting certain facets of information, which are very likely entirely relevant. A little bit of knowledge can give a very distorted picture. One of the reasons propaganda is so distorting is that it focuses on a little bit of knowledge, which may be true, but it is removed from the bigger picture and this changes the story entirely.

Historically, there have been particularly visual reactions to this. For example, graphic design has a history in political poster art—Eastern Europe, Cuba, the American Civil Rights Movement, The Vietnam War, CND, etc. This is not so prevalent today. Where do you see the visual arts political commentary currently?

The visual arts? Well, they are very prevalent today. A big part of the youth culture is gaining an understanding of the world from music, visual arts, graphics, comedy, and so on. It’s true you don’t have the remarkable virile character of the poster art of those particular periods, or at least, not that I am aware of. But it’s taking other forms.

What other forms do you see are more prevalent?

Oh, just watching my grandchildren; music, for example, which has political content—I don’t grasp it, but they do. Or film. Most films these days have a similar influence.

With this political content, do you feel that propaganda has an inherently political agenda?

No. It depends on how broadly you interpret ‘political’. People who have some message or doctrine, they’re all typically prepared to use the most attractive ways in the control of thought to make it work for them.

People who have some message or doctrine, they’re all typically prepared to use the most attractive ways in the control of thought to make it work for them.

You mentioned film and music. Do you subscribe to Marshall McLuhan’s phrase ‘the medium is the message’?

I understand what he is saying. There is some truth to it, but I don’t think it’s a good idea to accept that it applies to everything. There is no doubt the medium in which some messages are conveyed may of course have a major effect in fulfilling them forcefully and dramatically. For example, I have seen documentaries and films that have been incredibly moving, as with music of course.

In light of heightened media coverage of conflicts and international upheavals, has the media replaced ‘reporting’ with ‘entertainment’ for the sake of ratings?

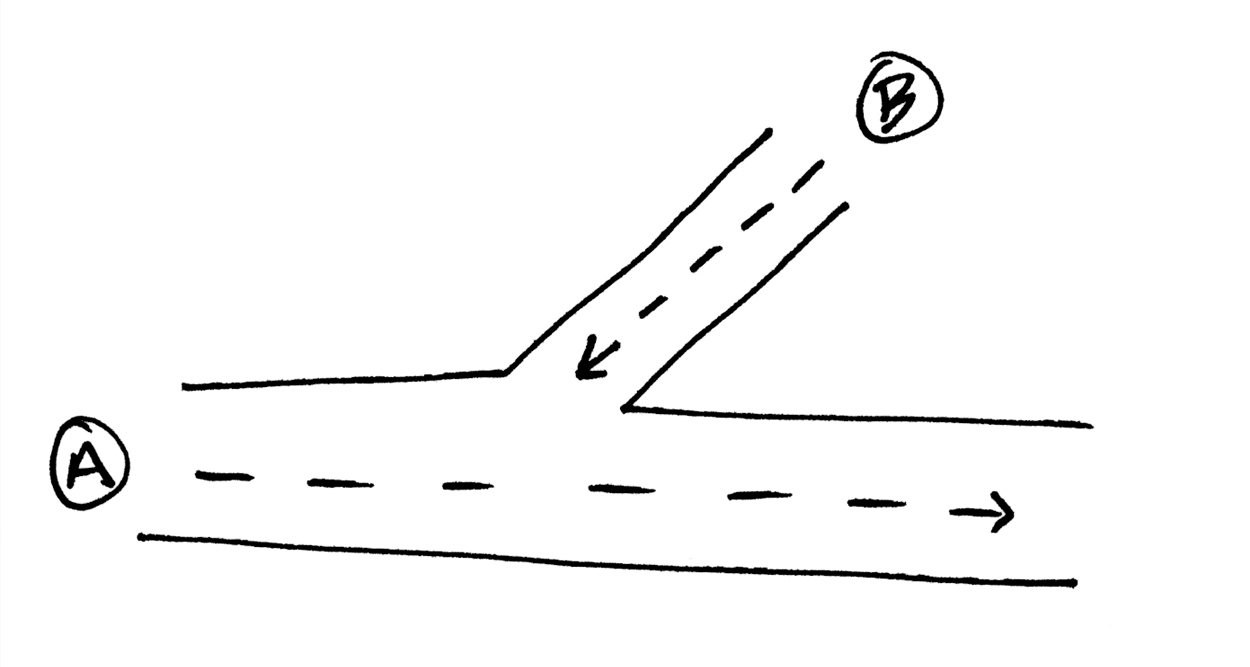

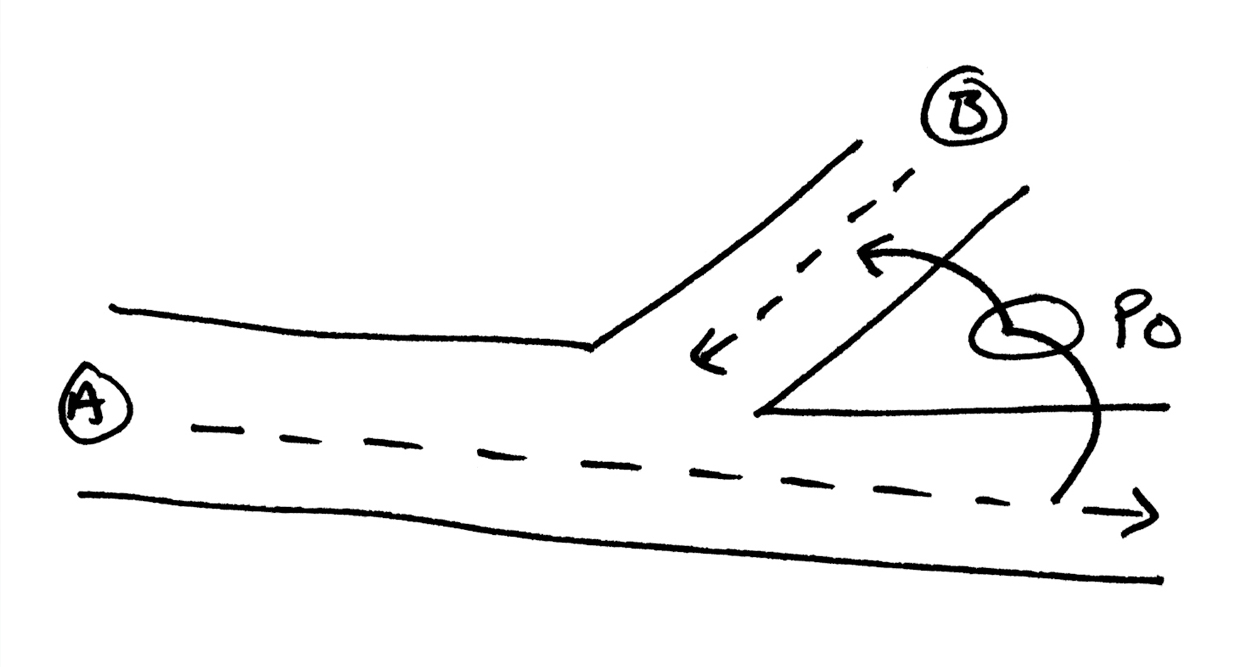

I’m not so sure there has been increased media coverage. In many ways it’s the opposite. For example, embedded journalists do not report directly. Their reporting is indirect. In contrast, journalists who are out in the field and who are not embedded within military units get a good picture of what is happening, but they are outside of controlling it. That is the reason for the recent practice of insisting on embedding reporters. And generally this practice is not just used by The Pentagon. It is also used by the major corporate media, which often will not purchase material from non-embedded reporters.

The craft of journalism is a very honourable one and there are people who do it brilliantly and courageously. But it is also very easy to become embedded (to borrow the word) into a system of doctrines and perspectives, which very much narrows and distorts the picture of what is being presented. And there is a lot of that.

How can we counter this?

The way to counter that is by compensating for those clear and obvious distorting perspectives by looking for other sources, by reading between the lines, by comparing today’s news with yesterdays.

There are even some simple tricks. For example, if you read an article about a current contemporary issue, say in The New York Times, or any one of the world’s major newspapers, you see the front-page story, with a big headline, and this follows on in a continuation page. I have learned over the years a useful practice, which is to start reading the article from the end. That is, pick the last few paragraphs on a continuation page and read them.

What you find very often (I don’t know if this is done consciously by journalists) is the material there is very significant and is marginalised to a degree because it is hidden at the end where people are unlikely to see it, except for the really dedicated. What is in the first paragraph, which is basically for the headline writers and the editors, tends to veer more towards the accepted party line. Of course, it’s not like an algorithm. It doesn’t work mechanically, but it is one of many devices people can use (and there are many) to decode the material that is being presented and to penetrate the reality.

In some respect, it’s not unlike the sciences. Mother Nature doesn’t tell you, ‘This is the important information’. You have to find it; you have to pull it out of masses of irrelevancies. The difference in reading the media or the journals, etc, is that Mother Nature doesn’t have an agenda. It’s not trying to persuade you.

The way to counter that is by compensating for those clear and obvious distorting perspectives by looking for other sources, by reading between the lines, by comparing today’s news with yesterdays.

Of course, that would rely on education, general knowledge and a will to actually seek out that information.

One has to be careful about that, too. In fact, George Orwell made an interesting comment about it that should be better known. Everybody has read Animal Farm [1945]. But very few people have read the introduction to Animal Farm. The reason is it wasn’t published. It was discovered later in Orwell’s unpublished papers.

The introduction is interesting. It’s not his greatest essay, but it is interesting. It’s about what he calls ‘literary censorship’ in England. In his introduction he states the book is about the hideous controls enforced by a totalitarian state. But in free England, it’s not very different. He says in England it is possible to suppress unwelcome thoughts without the use of force. And he has a few remarks on how it’s done. They are brief, but basically correct.

He says one reason for this is that wealthy men own the press and they have every reason not to want certain thoughts to be expressed. And the other reason is a good education. Go to the good schools (you have your Oxford and Cambridge), and you simply have instilled within you an understanding that there are certain things that wouldn’t do to say—or, for that matter, to think. And you have it internalised. That’s one of the effects of a ‘good’ education.

It’s my view, and I have occasionally written about this, that if you take the opinions of Americans, which is a very well studied society, on a wide variety of issues, they are considerably more civilised and constructive than the policies of the political class and, for the most part, the intellectual class. I think the reason is that they are just less indoctrinated.

Do you see entertainment playing a role as a tool of propaganda?

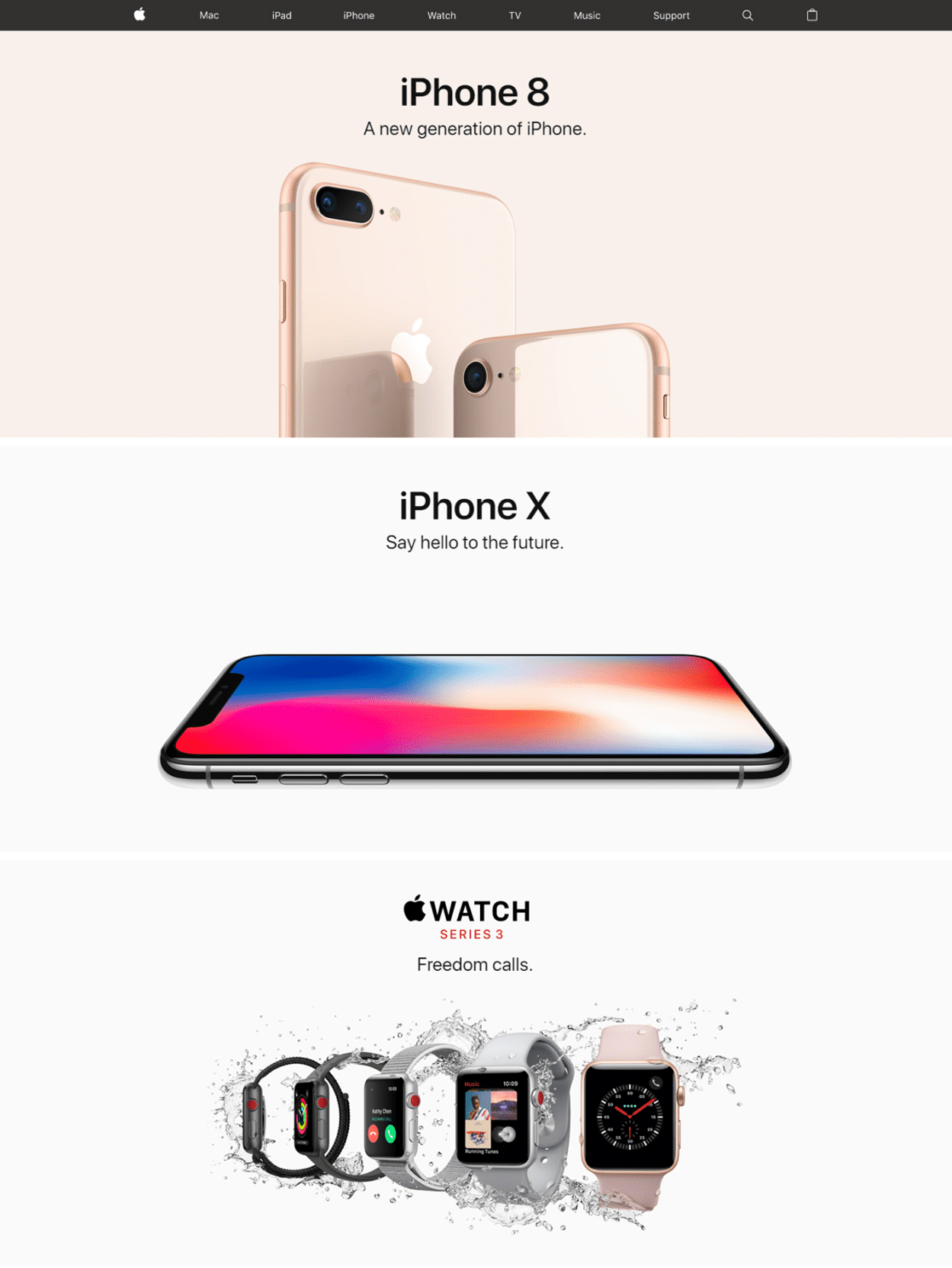

It has an enormous role. Look at a television ad: if we lived in a market society and there were advertisements on television, they’d resemble what you study in economics courses, which tell you a market is based on informed consumers making rational choices. So the ads would give you necessary information about the product. But when you look at an ad on television, say a lifestyle drug, is it trying to turn you into an informed consumer making rational choices? No.

Businesses are spending hundreds of millions of dollars a year to create uninformed consumers who make irrational choices by entertainment, by delusion. The lifestyle drug doesn’t say, ‘Here are my characteristics’. It has a model or a football player or somebody saying, ‘Ask your doctor whether it’s good for you. It’s great for me’. This is followed with a presentation of a marvellous scene showing how great it is. It just happens to be entertainment but it is primarily intended to be delusion. It’s oppression and an undermining of markets.

It’s the same method public relations companies employ to sell [political] candidates. They don’t want you to know the candidate’s stance on issues. They want you to be deluded by imagery of their qualities and their personalities, and so on. And pretty much the same measures used to undermine markets are used to undermine democracy. And that’s through a kind of entertainment.

Businesses are spending hundreds of millions of dollars a year to create uninformed consumers who make irrational choices by entertainment, by delusion.

Is it fair to say whatever ‘delusion’ advertising might offer that it is, in fact, a form of education of the masses—on a large scale—somewhat akin to the indoctrination of the political and intellectual classes Orwell discusses?

If you change ‘education’ to ‘miseducation’, that’s more or less true. There is a certain similarity of intent and of process.

Earlier you mentioned advertising and its tendency toward using elements of propaganda. Do you think, in the present ‘cult of the consumer’, graphic design and advertising are behaving irresponsibly?

In more honest days it was called propaganda. If you take the book written by one of the founders of the American public relations industry back in the 1920s, Edward Bernays, he wrote a particular book, kind of like a handbook—and it was just called Propaganda. During the Second World War, the term propaganda took on a negative connotation. It became associated with the Nazis and the Russians, and so on. So the term fell out of use in English-speaking countries. In fact, it is still in use in some other languages. But in the English-speaking countries, the term propaganda was restricted to the propaganda carried out by enemies. In contrast, what we do is called something better, like ‘information’.

In some countries it gets pretty funny. Take Israel. Hebrew used to have a word for ‘propaganda’. Now it’s used in reference to the propaganda of others. And it has been replaced in Hebrew by a word that translates as ‘explanation’. That’s Israeli propaganda.

The usage carries the presupposition that ‘since everything we do is obviously right, we don’t have to convince people. We just have to explain it to them’. Well that’s a good technique of propaganda and we [America] use a similar one.

Another phrase might be ‘manufacturing consent’.

Well, ‘manufacturing consent’ is a phrase that I’ve used but I borrowed it. I borrowed it from the leading public intellectual of the 20th century, a most noted and honoured figure in the media, the liberal progressive, Walter Lippman. His argument, back in about 1920, was that there was, what he called, a new art in democracy—namely ‘manufacturing consent’ to decisions made by the leaders.

He had a theory that the public is irrational, they are hysterical outsiders, a bewildered herd. For their own benefit, we, the wise, serious, responsible men, must manufacture consent to what we know is in their best interest. It would be too dangerous to let them make their own choices.

It’s like speaking to a three year-old. You wouldn’t want a child to run into the street so you grab their arm and pull them back. As responsible intellectuals, like Walter Lippman, we have a task of ensuring that the dangerous and irrational outsiders—the public—don’t enter into public affairs.

Edward Bernays said pretty much the same thing in his book. He called it ‘engineering consent’. He said the intelligent minority, namely us, must engineer the consent from these stupid and ignorant masses—the public—for their own good, of course.

And this is not right wing. These are the liberals on the liberal left. And it’s an old view of the liberal left. Notice that it is very similar to Lenin. There is a striking similarity between Lenin’s doctrine and progressive liberal democratic doctrine. I think that is one of the reasons why people flip so easily between one position and another. It is basically the same doctrine: ‘we’ know the right way and they are too ignorant or stupid to understand it so therefore ‘we’ have to drive them in the right direction, by force if necessary. And if we can’t achieve this by force, we will do so by propaganda, by engineering consent, by entertainment, and so on. But the principle is very much the same and it runs right to the present.

It is basically the same doctrine: ‘we’ know the right way and they are too ignorant or stupid to understand it so therefore ‘we’ have to drive them in the right direction, by force if necessary. And if we can’t achieve this by force, we will do so by propaganda, by engineering consent, by entertainment, and so on.

As you have mentioned in one of your books [Imperial Ambitions (2006)], there is a direct relationship between propaganda and privilege. How does this manifest itself?

One relation is (you can see the history develop very clearly) as countries became more democratic, through popular struggle—and remember it was a struggle, it was never a gift—as more and more rights were won by the public, for example the rights for women to vote, the rights of unions and so on, the power to coerce was reduced. And as the power to coerce was reduced, educated sectors, like those we quoted, recognised that it would be necessary to turn to another means of control. We can’t control them with a club anymore so we have to control them with propaganda because we are more privileged, more right. And that was explicit.

Another effect, which I think is more demonstrable but more subtle, is what Orwell was talking about. That is, the more privileged and educated you are the more likely you are to be subject to indoctrination.

Sometimes the elite are extremely frank about this. For example, after the 1960s, which was a very civilising and democratising era, that’s why they call it the ‘Time of Troubles’, things changed dramatically. This period immediately raised the level of civilisation in countries, and not just here [America]. And that was terrifying for the elites.

In fact, it was called a ‘crisis of democracy’. There was so much democracy they had to do something about it. I’m now just keeping to the liberal internationalist sectors, not the reactionaries. Now, their position was explicitly that we have to move the mass of the population back to apathy and obedience. And in particular, we have to ensure that the (and I’m virtually quoting now) ‘institutions responsible for the indoctrination of the young’ do their job properly to prevent any further ideas like these from developing. Carry out your task of ‘indoctrination of the young’. That’s their phrase—on the Liberal side.

What about propaganda’s relationship with religion?

Well, it varies with different countries. I mean, there is a fundamentalist wave spreading all over the world: Hindu fundamentalism, Islamic fundamentalism, Jewish fundamentalism, Christian fundamentalism. It’s just about everywhere you look. And it certainly is being stimulated by propaganda. I don’t know if you follow this [in Australia], but take the mega-churches of the United States. The United States has always been off the spectrum in relation to religious extremism. This goes back to the early colonies and there are regular periods of great revival. [America] has always been deeply committed to religious fundamentalism—very different from most other industrial societies. I don’t think you’ll find any other country where half the population believes the world was created, maybe 10,000 years ago exactly the way it is now. You might have to go off and find a remote tribe in New Guinea or somewhere like that to find something similar. But it’s about half the population of the United States.

And this has now become organised, explicitly, via major propaganda efforts by public relations firms. One of the recent developments, which is quite dramatic, are these mega-churches. They are huge institutions where thousands of people are brought together and whipped into emotional fanaticism and religious zeal with what are called ‘charismatic preachers’ in some huge church in the middle of a region surrounded by satellite churches, all linked together by top-notch technology.

Watching these things, I have to tell you, it reminds me of childhood experiences, which I was too little to understand but I could sort of get the picture. I remember as a child, back in the 1930s listening on the radio to the Nuremberg rallies. I didn’t understand the words, but I caught the mood. It was scary.

Is there such a thing as good propaganda?

It’s almost a contradiction in terms. It depends on our values. If we regard it as ‘good’ for people to be free to make up their own minds, to have adequate resources and access to information, to think creatively and freely in their interaction with others—if that is our ideal, the enlightenment ideal, by definition propaganda is not good for us because propaganda is designed to undermine all of that.

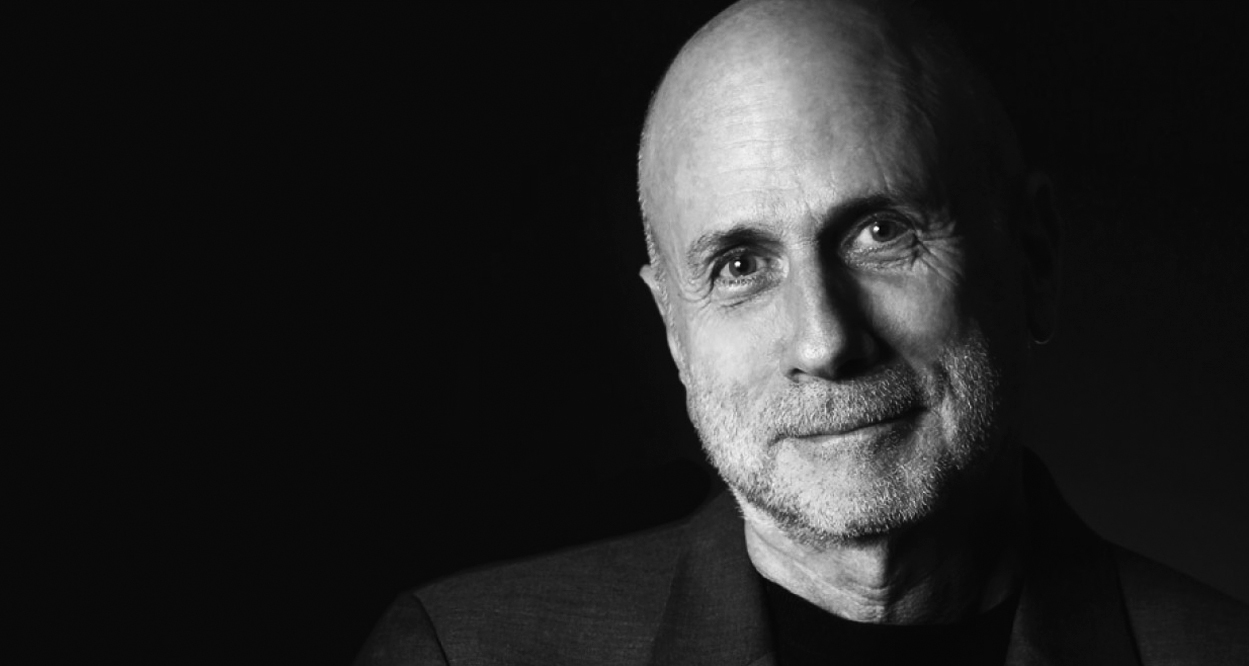

Image Credit:

Noam Chomsky portrait sourced on Britannica website