Ken Segall—best-selling author and ex-Advertising Creative Director for Apple—talks about the power of simplicity, citing numerous examples and case studies across the design and business worlds, and discussing his 12 years working alongside Steve Jobs.

Kevin Finn: The opening line of your book Think Simple sets the entire tone. It states, “Simplicity is one of the most deceptive concepts on Earth”—which is a compelling claim. But it could also be a little concerning for those who are seeking to adopt simplicity. In what way do you see simplicity being such a deeply deceptive concept?

Ken Segall: As a creative person in advertising, I come from a marketing background and I came to appreciate the value of simplicity in some of my earliest days. You know… How do I phrase this? [Laughter] When you have different bosses, different Creative Directors, and sometimes, when you present a really simple idea it gets rejected because it seems too simple or too obvious [laughs]. As a result, you end up getting into these discussions about: “Well, wait a second. That kind of simplicity really strikes home with people.”

But there’s this constant, I suppose, tension between people who don’t quite understand the value of simplicity. You have to fight your way through all those different layers. Especially when you’re working for a company with multiple levels of approval. Everyone’s second‑guessing and trying to make things “better” by adding layers to the idea—because everyone has to have their input.

So the challenge is not just to have the simple idea, but to have it recognised as a simple idea and to be able to keep it pure and simple, from beginning to end. That’s why I inevitably bring the Steve Jobs’ example into my story because—of all the people I’ve ever worked with or for—he was the one person who really understood simplicity and who was always looking for the simple idea. He went to extraordinary lengths to protect the idea, to keep it simple—from beginning to the end.

So the challenge is not just to have the simple idea, but to have it recognised as a simple idea and to be able to keep it pure and simple, from beginning to end.

It strikes me there’s probably an element of fear in people who say: “Oh, that’s too simple.” A feeling that something can be simple, but that it also needs to have a level of complexity within it for it to have some kind of weight or visible value…

Yes! I worked on the Apple advertising with TBWA/Chiat/Day. It was actually my fourth time working with the agency. I’d had many different stints with them over the years. They would do revolutionary work and receive amazing press coverage for it. At the time, I was formulating my personal belief in the power of simplicity and so I would often look at their work and think: “Well, it’s kind of obvious, isn’t it?” With this in mind, I’d Google to see who else had the idea. But I found nobody else ever did have the idea.

There’s something about a simple solution. It can be fantastically creative, and it often makes you think: “Well, certainly somebody did that before.” But then you realise, no-one actually ever did, which is so astonishing and impressive.

TBWA/Chiat/Day achieved that time after time. And it struck me—before I even got involved with Steve Jobs—that’s the way these guys worked. They managed to come up with ideas which strike a chord with you. Ideas that almost seem familiar, and yet they’re still surprising, wonderful and fresh. That’s when I really started to recognise the power of simplicity. It can appear so easy.

So the arguments I used to have about simplicity were because it’s only obvious when you see it done and when you think about it in hindsight. Those kinds of ideas connect with people better.

Of course, Apple had the benefit of producing amazing devices. Yet there was nothing terribly familiar about what they were doing because it was ahead of its time. But, if you look at the principles in the advertising we created, it really was very simple. I felt it reinforced the whole belief Steve Jobs had in applying the power of simplicity in many different ways inside the company.

So the arguments I used to have about simplicity were because it’s only obvious when you see it done and when you think about it in hindsight.

It reminds me of a conversation I once had with Dr. Edward de Bono where he suggested design can be simple and obvious in hindsight but not particularly simple and obvious at inception. It requires one to first wade through complexity in order to arrive at the simplicity. We have to do all the heavy lifting on behalf of others and, in doing so, put them in a position to see the simplicity presented to them…

That’s so true. When you look back and think how simple it is, or how simple it seems to others, it’s a reminder of how much incredible work, debate and anguish went into it. And yet, it often ends with people saying: “Oh, that’s so simple.”

In my book Think Simple I interviewed a few Australian leaders. One of them, Laura Anderson, creates strategies for very complicated companies. And it reflects what you just said. She requests to see all the company’s complexity. That’s how every project starts. She says: “I want it all on the table, just pour it on. We’re going to go through all this complexity and distill it into something simple.” So, you need to start with all that—and she’d create something simple from all that complexity; an actionable strategy that actually guides the behaviours and decisions, which spring forth from the simplicity. That takes a lot of work—and they pay her a lot of money to do it.

You also mention in your book that many companies behave as if simplicity will happen all by itself. This suggests leadership and deliberate action are the foundation stones of simplicity. So why is it so hard for some leaders or businesses to adopt an approach of simplicity?

That’s a very good question. I think it’s because it’s so obvious. That’s why I say people think it’ll take care of itself. Clearly, most people want things to be simple, so there’s a desire to have a simple idea which can then be executed.

But I believe, if you really understand the nature of simplicity, and you work hard to create something wonderfully simple, it takes a lot of effort and it needs attention. For example, with a lot of companies I’ve worked with previously, at the beginning of every project someone would typically stand up, make a pretty strong speech about how they’re going to do it this time, how it’s going to be so much different than last time. And then it ends up being a a pile of crap again because—suddenly—other people get their fingers in it. It’s a case of having to please ‘these guys’ and ‘those guys’; and do the research around the country; and revise it three or four times. Of course, before you know it, it’s not simple anymore. I believe people who don’t truly appreciate the power of simplicity tend to let it go along the way in the form of compromises.

I believe people who don’t truly appreciate the power of simplicity tend to let it go along the way in the form of compromises.

I guess, in many ways, it refers back to the point we discussed earlier about the pitch process where, oftentimes, the pitch process becomes self-selecting. Verbal identity helps that self-selection, in terms of who you might attract. For example, the gym you gave as a case study, they will attract a particular kind of person who is looking for that experience. It is self-selecting.

Absolutely! They know exactly who they want. They don’t want some 20 something that just wants it to be cool and hip. They want somebody who is an elite athlete and they’re obviously clearly positioned that way. It may not work as a mainstream proposition— it probably wouldn’t—but for them that’s absolutely spot on.

It’s a niche market. They know exactly what to do, what they want to do, and I’m sure they have included within their language that it’s not just about the brutality of the experience, but also the benefit, the outcome.

Absolutely. Yeah. You get the full leadership piece that they have on their site about the kind of development and how they grow their people. Everything is pretty extraordinary. You can see the whole package, in terms of this intensity and brutality on one side, but you also see yourself coming out the other end as the best person you expect to be.

You’ve mentioned ‘innovation’ a few times, and in a recent conversation we briefly discussed the issue of innovation and its potential overuse in the context of business expectations. My view is that true innovation is a game changer, and usually only happens over a longer period of time. You argue that the idea of innovation can actually be a language tool, which can be used regularly to specifically leverage or persuade in a client situation. Can you expand on this?

It very much comes down to whether you want to narrowly or broadly define the nature of innovation. It’s not so important to me. I probably use the term as a short-hand because there are lots of different types of innovation. There is business model innovation. There is service innovation, client innovation. There’s all sorts of ways to actually cut that conversation up. For us, the idea that innovation needs to be something big isn’t the case, because innovation can be evolutionary by its nature.

You don’t necessarily come to an end, but we see the exploits and end results of innovation, and usually those innovations are a consequence of months, years, decades of evolution, and work, and thinking. That’s why I probably have a wider view of it. I know when you look back on the history of branding it has evolved, but it has been done through certain individuals and organisations who question the way branding works and find a better way of looking at it, which actually moves things along.

For us, the idea that innovation needs to be something big isn’t the case, because innovation can be evolutionary by its nature.

You touched on something else in your book, where you claim most business strategies are based on cold, hard facts, but that simplicity is based on an understanding of human behaviour. I assume understanding human behaviour relies on data—but also on intuition. And that’s easier said than done, particularly because most business leaders were probably trained in cold, hard facts. So it must also take behavioural change on the part of business leaders to move into this space. If so, how can they adapt?

Many of the people I talked to for the book were already of this belief and persuasion. I sought them out because their companies fit a certain model. Many said they want to see the data, but they don’t want to lose sight of the emotional reactions and some of the things that can’t necessarily be quantified in data.

I’ve always thought Steve Jobs was the great example because it takes boldness to do that. I mean, he was willing to gamble tens of billions of dollars on something that he had no proof of, other than what he felt in his gut. Most companies don’t do that because even the CEO’s are afraid. Their job is on the line. If it doesn’t pan out, then the Board’s probably going to fire them.

So, I imagine most people get into this mode where they need validation. And that validation only comes in the form of things that can be measured—in very cold ways.

That points to a level of confidence. I never met Steve Jobs but from what I’ve gathered—through reading, videos and media—he had an abundance of confidence. Some might have interpreted that as arrogance, but it was confidence nonetheless. Perhaps, in the corporate world, it’s a lot harder for some leaders to have that confidence without the validation.

That’s true. And it was actually what I was leading to. It does translate to confidence. I agree a hundred percent. And you’re right, there’s a fine line between confidence and arrogance. I think a lot of people would look at Steve Jobs and say: “Yeah, he was really arrogant.” But he had a great sense. He trusted his own experience. A lot of business leaders I’ve spoken to think along those lines. For example, they say things like: “I’ve been doing this all my life. I know this business inside out, so why would I need to rely on something like validation, when I know in my gut this is correct? I don’t want to waste my time,” or: “I don’t believe those numbers.” They have the confidence to make decisions and literally risk large sums of money going in a certain direction. But, they don’t it blindly. That’s important to mention. They do look at the numbers. Obviously, they don’t want to make stupid mistakes. But they give themselves a lot of credit.

In contrast there are businesses like Intel—which I like to bash, but I used to work there so I know. The highest level off marketing people would be in meetings—two or three people. Then we’d have the creative team, and the agency people who were, you know, marketing experts. So you’d think with that amount of expertise in the room, they could just say: “This is good and that’s bad,” or: “We like this the best. Let’s go with it.” But they were unable to make those decisions, because nobody wanted to make a mistake. They didn’t have that kind of confidence.

They would pick two ideas—they couldn’t just pick one—and then they’d do research all around the world, in many different countries, to get comments. Then they’d actually produce two entirely separate campaigns, before testing them to make sure they were going to run the right one. It was so much time and so much money. When we worked on Apple I always felt like we were almost winging it. We’d have a debate in the room. We’re smart people. So smart people would agree that this was the right idea. And then we’d go off and produce it. Essentially, we’d short‑circuit a process that normally takes three months in these other companies. We’d do it in three weeks—from presentation of the idea to the finished product.

That suggests it’s more about informed intuition—one that is informed by experience, by data, and by the other people in the room…

Yes! It’s about not being blind to the facts and experiences that others in the room bring.

John McGrath is one of those people who disparages other companies because they would spend so much time researching what was important to the buyers. He said: “I’ve been in this business my whole life. I’ve bought and sold property all my life. I know how I want to be treated. That’s all I need to know. I just want to treat customers with respect, not lure them in by avoiding to give them the prices and suggest they have to come in to the office so we can talk about it.” He said: “I don’t want to be treated that way, so I’m not going to treat my customers that way.” And it seems to have served him fairly well.

In your book, you throw a curveball by suggesting: “There’s no such thing as simplicity, only the perception of simplicity.” Doesn’t that undermine the power and attraction of simplicity if it’s all about perception?

Yes and no. Actually, I would say no, because it’s the basis of my thesis. [Laughter] But my point really is, so many things appear simple to us, but they’re not—for all the reasons we’ve already talked about. There’s so much work and debate; so much revising, and all the stuff. Hopefully, it finally gets in front of someone and they think: “Oh, that was simple.” But it wasn’t simple getting there. Yet you perceive it as simple.

For all the reasons why something might be simple or complicated, it really doesn’t matter. The important thing is the customer’s experience with your product or your service. If they feel like it was simple, then it’s simple. The simplicity is real. So, it’s all about creating that perception, working on that perception.

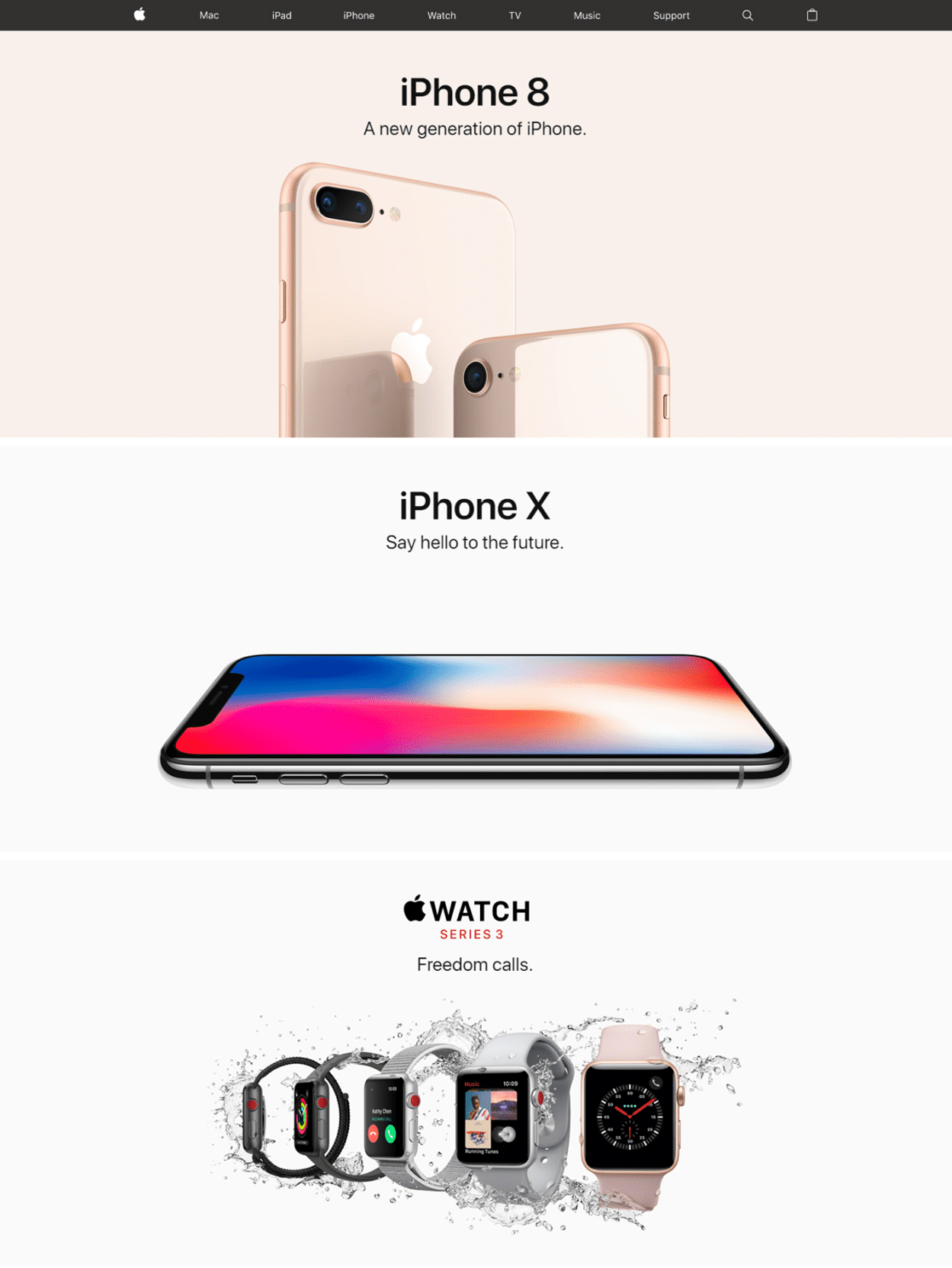

For example, say a company has 40 different products—and they need to have 40 different products because they have many different kinds of customers. You don’t have to design a web page presenting all 40 products at the same time. You can group them in certain ways, like ‘good’, ‘better,’ and ‘best’. It’s about creating the perception that it’s a simple experience, even if—technically speaking—it isn’t.

Again, I use Apple as an example because they only show a couple of models of computers, even though you can configure them to create 10, 20, or 30 different models. But they don’t prepackage all those different models and try to get you to choose one or the other. Someone may think there’s an easier way to approach the problem and present all their products at once. But the likelihood is, most people might think: “I have no idea where to even start with these guys. But Apple just made it so simple for me so I’ll go there.”

So it’s that perception of simplicity, even though the number of models Apple offers compared to the other guys might not be all that different. It just appears to be different.

Using your website analogy, it’s the same with content and how it’s being presented. Through the navigation design, there is an opportunity to offer the perception—or the impression—that it’s easier to navigate. Even though the amount of information on the website hasn’t changed, just how it’s accessed….

Right, right. To your point, it’s my view that if you make that experience feel so simple, then that’s when people might talk to their friends or their colleagues. They might say: “Oh, I had a great experience with this company. You should check them out.”

Whereas if you have to work to get what you need, you’re not prone to talk up that experience. That’s how Apple is always attracting people, because customers talk about their experience. And friends and families get influenced by that.

If you have to work to get what you need, you’re not prone to talk up that experience. That’s how Apple is always attracting people, because customers talk about their experience. And friends and families get influenced by that.

Apple is often seen as the holy grail. They’ve moved from their customers being ambassadors and champions to almost being evangelists. It does come down to the experience—and Apple’s understanding of the customer experience—and then presenting it in simple terms.

Yes! Though, I try to issue disclaimer at various points because I always go back to Apple, and it’s actually an unfair example because they make these beautiful, shiny things and people have these experiences through owning them, holding them. It’s very different from a company who might, for example, make small engine parts. It’s difficult to fall in love with that company in the same way you might with Apple. But you could fall in love with the experience of dealing with that company.

I’ve spoken with telecommunications companies and TV cable companies, those sorts of businesses. They understand their customers are never going to love them like Apple customers love Apple. But they can create an experience with them that is above what they produce and more about the customer service and experience.

Apple creates love. Everyone can create love, to a degree, but for some companies it can be difficult. For some, the nature of some companies simply means: it is what it is. Still, like I say, the experience—that feeling of the company—can be simple versus complicated.

That reminds me of a conversation I once had with Blair Enns—a Canadian consultant in the creative space. He shared a story where a client once said: “We want to be the Apple of our sector, or the iPhone of our sector.” And they say it with great enthusiasm. He let it hang for a few minutes and then replied, saying: “OK. But are you brave enough?” This goes back to the confidence issue because I think a lot of people, when they talk about Apple, they’re only looking at the results, not the work or the process that Apple went through in order to get to the end result. I guess that’s also why you need to include your disclaimer about Apple because it’s unique. Regardless, I think people tend to base their judgments on what Apple ‘has’ achieved, not ‘how’ they achieved it—which is the hard work. And that’s where courage and confidence is required.

Yeah. [laughs] It’s funny because, in my advertising consulting life—either through my own experiences or people I know who tell me—clients have said: “We want to do something like what Apple would do.” Because, again, there is a perception that it looks simple, so people think it is. And this feeds the perception that Apple achieved it overnight. But it was over 20 years—doing it over and over and over again, building loyalty among people who appreciate a company that makes wonderful things simple.

I assume most organisations and businesses understand the importance of simplicity when it comes to products, systems, and processes. However, you also talk at length in your book about the importance of simplicity with regards branding, including simplifying internal communications around mission, and values—those sorts of things. Most organisations might not make a connection between simplicity and branding so why do you see simplicity—in these particular areas—being so important for organisations to embrace?

Well, I just think that if you have those clear missions and clear values—and again, it reflects many of the conversations I’ve had for the book—I was hearing the same things over and over again. It’s about guiding a company to avoid standing over people’s shoulders telling them they’re doing it right or wrong. If staff understand the values of the company, or they understand there’s a clear mission, then when they’re creating products or making decisions in marketing, or whatever, they’re all consistent. They’re all moving in the same direction.

If staff understand the values of the company, or they understand there’s a clear mission, then when they’re creating products or making decisions in marketing, or whatever, they’re all consistent. They’re all moving in the same direction.

In fact, I recently spoke to a friend of mine, who I had lost touch with for a while. He was telling me why he’s no longer with the company he worked for. He had philosophical differences with the company because it’s from a world where you just keep people churning out new product ideas. The problem was they couldn’t really focus on anything, which made it hard to invest money in any one thing. The company was just doing way too many things and, ultimately, he just had to leave because of this different view around simplicity versus complexity.

So, I think if you have that appreciation through the power of simplicity it prevents you from doing these types of things. It helps ensure you avoid inconsistency with your Mission and your Values—and it lets people do their job because they know how to do their job without other people telling them how to do their job. But, ideally, everybody’s on the same wavelength.

The CEO of The Container Store Kip Tindell is a good example. It’s a very big national US retail chain. He said they have a set of values, which they indoctrinate their people with, so that everyone knows how they’re expected to behave—what end result they want to achieve. And then they don’t say anything more to them. It’s up to the individual to creatively execute. They can work any way they want to work, as long as they don’t go against the values. So it empowers them to be creative in their jobs and it makes them feel like they’re doing their thing, but they work for this bigger company. And, this company is quite amazing. I believe that over a period of 25 years they’ve never had a down year. It’s incredible.

I guess it’s because it has become cultural through simplicity. That said, I believe organisational culture can’t be—or shouldn’t be—designed or manufactured. It can be facilitated and nurtured, of course, but it must grow and evolve organically. So, are you suggesting that, through simplicity, the vision and mission can become cultural, rather than just statements of intent?

That’s how I put it in the book, where all these things combined create the culture. There are cultures of complexity and this can drive people away. There are quite a few examples where people I spoke to attributed their success to having a strong culture, or in the case of Ted Chung in South Korea [CEO of Hyundai Card], he faced a total mess when he arrived, where the company was projected to lose two billion dollars in the first year.

But they turned it around. What he did to the culture was amazing. In fact, I met him because I was doing a presentation in Seoul. While I was there, someone suggested visiting the business. I met him and got a tour of the company. By the time he was done, I wanted to work there!

[Laughs]

I thought: “This is the coolest place!” The architecture, the design of the lobby, the vending machines, the designer furniture—all this stuff. He told me he wanted to change the culture of the company. He knew it was all about how credit cards represent a lifestyle and they all needed to embrace that thinking. So it became all about about design. Of course, I was thinking: “How could a credit card company be about design?” But it was! And it permeated the workplace. It completely changed the way people thought, the way they design their cards and the type of events that they would sponsor. It became all about lifestyle. They did a complete turnaround. He was my big culture story in the book.

And then there is Telstra, which has had some horror culture stories. I talked to Telstra Executive Robert Nason at the end of his third year. He said they’d made a lot of headway, considering all the things that are typical of a big company. And a lot of it’s in the culture.

An example he offered was around presentations. He enforced a rule where there had to be one slide for every minute of a presentation. Meaning if you’re giving a 45‑minute presentation there needs to be 45 slides—and it needs to stay on topic. Previously, if you did that, people might look at you like some kind of a renegade, thinking: “You don’t belong here.”

So, it feeds on itself if your culture is one of simplicity—and I use Apple again as an example. I was in plenty of meetings without Steve Jobs where people were preparing their presentations. They’d help each other by saying: “You’ve got six things on that slide. That’s probably a bit more confusing than it should be. Can you get it down to two?” And they would.

People were always looking to help one another to do something that was more consistent with the culture. Culture has a lot more than simplicity but having this as a central philosophy is stronger—as opposed to a culture where processes are more important than anything else and where people must follow the process above all other things.

Culture has a lot more than simplicity but having this as a central philosophy is stronger—as opposed to a culture where processes are more important than anything else and where people must follow the process above all other things.

In terms of advertising, that drives people crazy because at Apple, creativity was important. If we had a new idea on the [production] set, that was the most fun part of working with Steve. He’d approve one commercial, and we’d show up with 10. We’d always do the one we’d set out to do and oftentimes he went with the original one. But other times, he’d get excited about something that we hadn’t even thought of before he visited the set.

In contrast, at Intel or Dell—or one of those types of companies—you’ve already sold the idea to 30 different stores around the world. And if you don’t end up with the exact thing they approved, they’re never going be happy.

At Apple it was a culture of creativity, where the best idea should be produced, even if that meant revamping the schedules. With other cultures—where it’s all about processes—creativity is seen as a lesser value.

It strikes me it’s a deliberate choice that people make, possibly because in some organisations it’s easier to hide within complex layers, where it’s easier to shirk accountability and avoid responsibility. Is this a byproduct of a bureaucratic organisational structure, or do you think that retaining complexity might be more intentional for those reasons—to sort of cover your tail?

It’s hard to say. But pretty much every organisation starts small, in some way—and then it grows. So somewhere along the line it changes. And when it gets bigger, it develops processes. It brings in smart people to ‘run the company like a big business’ and can lose sight, as a result.

Steve [Jobs] was able to straddle this. He built Apple as the world’s largest startup. He didn’t want to lose those values. It’s that cultural thing again. Your job, your company, it’s all about the culture—and within that processes can be created but the values show up.

In marketing, there are those who have embraced the whole ‘honesty’ thing—which they obviously should. But then there are many companies that are tempted to think: “Let’s just use a little hyperbole here.” This can be really misleading.

I think your whole professional life is about finding that place to work, where you really feel like you’re in tune with the values of the company.

By the way, you talked about how hard it is to do something simple. It just reminded me of the quote: “If I had more time I would have written a shorter letter.” It’s attributed to a number of people, but the premise stands. It really is hard to do something simpler. It takes time and a lot more effort to reduce things…

I think your whole professional life is about finding that place to work, where you really feel like you’re in tune with the values of the company.

In your book, you touch on the issue of “faster, better, cheaper”. General consensus is that only two of these are possible at any one time. However, you propose it’s possible to achieve all three—but only if organisations tackle simplicity properly. How can simplicity achieve “faster, better, cheaper” without compromising quality?

The key is having really great people. And that was always a priority for Steve. He said many times that his most important job was hiring brilliant people. So, you’ve got really talented people; you give them responsibility; and you don’t threaten to bring in 10 more people when they failed to do their job. But that’s not about doing all the late nights, losing holidays with your family. It’s about getting a smaller group of people who can work quicker together. When Steve rejected our work we’d simply come back a few days later with new work. It wasn’t about getting six more teams involved if the work was rejected because we’d just have to sort through it all.

Sadly, the indications now are—in the absence of Steve—Apple is kind of…

Faltering?

Gravitating more towards the big‑company way of doing things where they have 10 different teams working on every project, with lists of events, meetings and things you need to be in. We didn’t have that. We didn’t have an official creative brief. Steve would give us the details on the product. We come back with ideas and then often use those ideas as fodder for discussion, which a lot of creative people hate—and they often refused to work in that way. But I actually found it to be fun because Steve couldn’t really understand how it would end up on TV unless he could see it. He didn’t want to have creative brief meetings. He just wanted to talk about work.

So, without all the different layers it happens faster. I often tell people about my experiences with Dell, IBM, Intel, BMW, how we would spend far more time creating a campaign than we did on Apple. We would spend less money because we wouldn’t be doing all the research and have too many people involved. And if you look at the work that came out as a result, it was much better than the work we did with the other companies. It speaks for itself when you have that simplicity of thought.

There are so many ways that simplicity leads to a better product. There are so many obvious examples with Apple and I’ve never understood why other companies try to copy the products but they don’t try to copy the the company—how it works. They don’t try to understand how Apple can do it time after time.

I guess some things just don’t really sink in. A good example is the iMac. By the way, this isn’t about creating just a style, but when the iMac was released Steve literally said: “In about two or three months from now, you’re gonna see a lot of these one‑unit things out there: all-in-one, easy Internet, the whole bit.” That seemed obvious to us—but it didn’t really happen.

I remember a meeting with him some time after the iMac launched and he said: “I personally don’t get it. We’ve showed them the playbook. And it’s become the best‑selling computer in the market. Yet people aren’t copying it.” Not that it worried him…

[Laughs] One way of translating this—and it’s mentioned in your book—simplicity was Steve’s greatest business weapon. That’s a really interesting way of synthesizing all the things we think about with Apple: design, attention to detail, craft, consumer awareness, customer experience, etc. You’ve boiled it all down to ‘simplicity as a business weapon’. So how did you see that having been translated practically?

For starters, clearly there are many reasons why Apple is successful. And I’ve seen this applied in so many different places: it’s in the organisation of the company, the advertising, the design of the Apple Stores. And there are so many different processes that they haven’t put in place. It was always in Steve’s head.

Especially when you look at things like the iPhone, or the iPod where Apple entered markets that were dominated by established companies. The music player market was looking for leadership because it was so splintered. There were a ton of them out there. So simplicity was his weapon because he used it competitively. And when all of these people laughed at the idea of Apple stepping into the phone market, a sector they knew nothing about and which was dominated by these giant companies—the fact he would even have the nerve, to have that confidence, and to think he could compete. And he basically took it over. It changed the whole course of how that the category developed from that point on. It really just shows the power of simplicity as a weapon, that he could offer something amazing to customers that’s really easy to use.

In fact, I worked on the original iPhone advertising development and in the initial briefings I remember the first meeting we had with the product manager. He said: “We all use BlackBerries here.” That was the accepted thing to use in business for email, etc. He went on to say: “But we don’t use around 80 percent of the features in a BlackBerry because we have no idea how to.”

So, the idea of the iPhone was that you wouldn’t even need an instruction manual. It would just be so obvious how to use it. The idea was you would simply use the features because they’re right in your face. You don’t need a manual for it.

I think it’s hard to deny that it’s one of the most powerful competitive weapons because, if you give the customers a choice of a difficult way or a simpler way, human nature will go with the simpler way.

I guess simplicity comes along in stages. You look back at things that we thought were simple years ago, but which were actually terribly complicated. We all grow up together and become more sophisticated. But I think it’s hard to deny that it’s one of the most powerful competitive weapons because, if you give the customers a choice of a difficult way or a simpler way, human nature will go with the simpler way. So, if you can make that clear to people, to communicate you’re offering simplicity—and in the case of Apple, where there’s a lust factor for a cool‑looking thing, because the design is so beautiful—it’s hard to lose.

It’s actually amazing to me how Apple hit so many things at once. It got people to open their eyes because, remember, the company was previously a failure. When Steve came back, it was near bankruptcy. It’s an amazing story. With all the various movies and everything that has been produced about Apple and Steve, it’s a shame they never really captured that aspect of it. It was always about his temper, and all that kind of stuff.

The cult of Steve Jobs?

The business story is quite fascinating, from getting fired by your own company, and starting Pixar and all the things that made Steve what he was, what he became and then how we applied that to Apple when he had the chance to return. It’s an amazing story. I just really haven’t ever read it anywhere.

You included a number of Australian organisations—quite favourably—in your book, including Westpac Bank, Bank of Melbourne, and McGrath Real Estate, among others. Why do Australian organisations stand out to you? And how do you think they rate in terms of the adoption of simplicity?

I think almost all of the leaders had that confidence we talked about earlier. They just hit all the things I believe in—because I saw those characteristics work with Apple. They all have a common theme. They needed to create a brand and identify what the company is going to stand for. They talked about simplifying their storyline—and every single thing they did had to fall under that theme, right down to the way they designed their offices; how they interacted with the community or customers; the way they set up their phone support lines.

It seems obvious, but these things didn’t exist until they did! Someone had to come along and say: “This is what we need to do”—to crack the whip, so to speak, and to make sure everybody was in line with that singular idea, to understand that it’s going to gain value for them because everybody would line up behind that arrowhead.

Earlier you mentioned businesses usually start out simple and then, as they grow, they get more complicated. So, is scaling simplicity the greatest challenge? How do you fend off complexity creeping back in?

Yes. I talk about this frequently. There are big companies who try to simplify. There are small companies that are simple and need to defend against the forces of complexity as they grow. Interestingly, if you have a successful small company you don’t always think it was successful because it was simple. So you allow things to happen to it because you think it’s all about scaling. You think, as you scale, you need to do all these complex things. But then, you look back one day and realize just how complicated things have become.

How do you fend off the forces of complexity? It’s about ensuring the processes don’t become more important than the ideas—and being somewhat ruthless in enforcing the simple things that are defining your company.

How do you fend off the forces of complexity? It’s about ensuring the processes don’t become more important than the ideas—and being somewhat ruthless in enforcing the simple things that are defining your company.

Sometimes, as the Mission Statement gets more complicated, the values get less clear. And before you know it—as things grow—there is a decision made to bring someone in to handle things. They start applying big company values to your company. As a result, people become less passionate about the work, because suddenly they now have to operate under all these different burdensome guidelines.

One of my favourite cases is a Czech Republic soft drink company called Kofola. As they got bigger, the founder brought people in from big companies to help. But staff started getting very dissatisfied with their jobs because it wasn’t fun anymore. There was a creative group there and they had a messy workplace. The new regime cleaned it all up, made it ‘modern’. But it just felt like all the fun had been sapped out of it. That’s an extreme example because it’s so visible. But culturally, they were really a bunch of hippies making cool drinks, and when suddenly it was like a job, and you were just a part of a company, everything became sterile. They didn’t feel like they could even dress as ‘loosely’ as they had before. This dramatically changed the happiness level of the employees. The owner realised he needed staff to enjoy their work. So he got rid of those other people and decided to make the place messy again—the way it used to be. And things started taking off again. And they all felt much better about it.

So, the lesson is: it’s just as hard to scale culture as it is to scale simplicity?

Yes, because, as they get big most companies introduce processes so things are much more controlled—because failure seems to have such a huge price. There is a sense that: “We can’t possibly fail.”

When I was at Intel I couldn’t understand why they thought they’d go out of business if they ran a bad ad. At Apple, we ran some bad ads, you know? There are some things we developed that I would never show anyone. We thought it was good at the time. It didn’t work so we yanked it off the air and we did something else. It’s not like the company had to close down over it. You can still shoot for the starts—and failure is part of it. There’s no freedom in a culture where failure is unacceptable.

Of course, Steve Jobs would get mad at us when we did a bad ad. But he didn’t fire us. So somewhere in the back of my mind at the time I remember appreciating that we tried something new, because we believed in doing something different. We talked Apple into doing things sometimes and Steve would say: “I wish you guys didn’t talk me into that.” In those instances, he often just said: “You can do better!”

You can still shoot for the starts—and failure is part of it. There’s no freedom in a culture where failure is unacceptable.

Shifting gears a little, something that struck me in your book was your suggestion that: “since the dawn of advertising, agencies have built reputations on their ability to create outstanding brands because, the brand is arguably a company’s most valuable property.” I agree that a brand is arguably a company’s most valuable asset, but I have to challenge you on agencies building this. Don’t businesses build their brands—day in, and day out? Advertising agencies promote the product and service. And that’s important. But they’re not involved in everyday business—day-to-day. It’s the business which does it and therefore it’s the business that builds the brand. Would you agree?

First of all: how dare you question me! [Laughing] But seriously, I do think that maybe I’ve been fortunate to have worked with brands that actually value their agency’s input. Some more than others, of course. But I think we always considered ourselves as the steward of the brand because our advertising was the most visible thing they did. But, obviously, the brand is more than just the advertising. It’s PR and all the things that the company does and which add up to what the brand is.

But I think the agencies have a lot to say about that, and in the case of Apple maybe it was an unusual case because Steve Jobs loved marketing so much. He loved and understood the power of the brand. Many of our conversations were about that kind of stuff, whereas other other companies might not treat their agency that way.

We saw ourselves as being important and knew the advertising we put out really was going to shape the brand so it had to be consistent with the values, the level of creativity—all of that. A good advertising/marketing person needs to be extremely aware of what they’re doing to the brand work because you are a major contributor to what the brand is.

There’s a lot of movement in the creative industries, from technology to consumer behaviour, etc. Are you optimistic about the future of advertising? Where do you see the future of advertising moving towards?

It’s funny you should mention that because I watch a lot of TV at the moment, primarily to see the ads but I’m so amazed that we have this man [Donald Trump] as president.

I agree! Don’t get me started…

Well, sometimes I watch the news for hours every day. I can’t take my eyes off of it. And to think that it could all end in a nuclear war, it’s not even funny.

It’s horrifyingly addictive.

Yeah. He’s an idiot, but it’s fascinating. Anyway, as I’m watching I begin to wonder what the demographic is for CNN, because I’d hate to be in it—it’s largely pharmaceutical advertising.

It seems you have to be over 60 to watch and appreciate the ads. But sometimes I just lament the state of advertising. Perhaps it’s something people have done for decades. The Super Bowl is always a good example. I think people legitimately lament that the advertising was more entertaining 20 years ago than it is today. Now, it’s not even a surprise because half the time the companies do sneak previews a week before the Super Bowl—trying to get in before the other guys. It’s not even a surprise anymore. That’s all bad.

But it validates what I’ve believed for a while—there really aren’t great talents in the world any more—those really great agencies and individuals. How often do you see something that you wish you did? It’s not that often anymore. Ads are mostly a lot of ‘filler’.

But, once in a while, there’s something that just makes you say: “Wow! That was amazing.” But it only happens once every year or so. And that’s so few. Because of that, my mind always wonders what the discussion with the client was like. I wonder if it’s really what the creative people wanted to produce? Were they talked into it? I’d love to know the backstory.

Of course, advertising is so different today because of ‘digital’—which at first was so offensive to creative people and the agencies. They though of it as ‘busy work’. But now, you can do some of the coolest things because you’re not on network television and that frees you up to create different things. Some spend millions of dollars on videos, with budgets comparable to what you might spend on a traditional commercial. But it seems like that they’re just the only way to get a great idea out these days.

However, advertising is still about what it has always been about— the great idea. It’s everything. Once you have the idea you have more ways to get it out into the world today than you had previously. In the old days, it was print and television, that was basically it. ‘Outdoor’ [including billboards and poster campaigns, etc]. But now that there’s so many other ways and people are dreaming up new ways all the time.

But it’s a double‑edged sword, because it leads to advertising pollution. There’s stuff people are trying to advertise in so many places that it makes you start resenting advertising—more than you might have before! I wish there were more ethical advertisers around, who would treat advertising properly. Otherwise, it’s like throwing trash on the highway. We need more respect for our world and not dirty it up with things that are just annoying.

Earlier, you mentioned Hyundai Card, and Ted Chung, the Vice Chairman. You state that he believes: “The age of advertising is over, the age of expression is here. And when it comes to expression, design is one of the most important elements.” In your opinion, how does design, in practical terms, factor in the future of most businesses or organization’s success now and in the future?

I think design has become hugely important in the same way that it became important at Hyundai Card. And it’s beyond just product design. It’s the design of a company—it’s everything! There’s great value in designing beautifully, whether it’s a thing that can be aesthetically pleasing, or a company that just runs so well. People like being part of a company when it’s beautifully designed. So, I think design has far deeper meaning today than it did 10 or 20 years ago.

Design has far deeper meaning today than it did 10 or 20 years ago.

And civilization has collectively become more sophisticated. When you look at things that worked 10 or 20 years ago, they seem so unsophisticated now. But at the time, they were very sophisticated. As a civilization, we tend to appreciate things that we didn’t appreciate in previous years. I think design is now one of those things.

I’m trying avoid saying: “It’s all because of Apple” but I think Apple was a huge contributor to people being more aware of design-led companies; being more aware of the value of design. Apple have made products that are beautifully designed, where customers actually start demanding that level of design from other companies. So more companies have started responding to that demand. And now we have a lot of really beautifully designed products in the world. I believe more companies are now conscious of the value of design in many different ways, including the structure of the company itself.

Previously, design was seen as a luxury—something to have as an extra. Whereas today, for many companies it has to shifted to an important baseline. It’s become central to how value gets added to a business, and how success can be achieved. It’s not seen a luxury anymore…

I think if you have hopes and dreams of excelling and being the best in your category, if you’re not concerned with design, you’re not gonna make it.

If you have hopes and dreams of excelling and being the best in your category, if you’re not concerned with design, you’re not gonna make it.

I’ll finish on this question—and it might be a little bit left-of-field. In many instances, technology has proven its potential to be a great catalyst for simplicity. Apple is a great example of that. It’s also a fact that AI (Artificial Intelligence) and machine learning is going to obliterate many professional and industry sectors. However, there’s an argument that creativity and design won’t be affected as much—because of the human factor in creativity. But AI can already design a logo to an acceptable level, and it’s likely to improve upon this. Designing a logo could be seen as a small achievement right now, but that could just be the tipping point. In your opinion, how do you think technology is going to impact design and creativity in the future?

That’s a good question. It’s funny because all my life I’ve been a sci‑fi [science fiction] fan. Those are just my favourite kinds of movies. Now that this stuff is actually becoming reality—and you hear people like Stephen Hawking or Elon Musk saying we’re all going to die because of AI—you think could it really turn into Terminator, where the machines enslave us. In terms of creativity—I could be very wrong about this—but I believe advertising will always need to have a good idea and I find it hard to believe that machines can actually create. It could be my famous last words because, if a machine could literally think like a person ultimately I’d be wrong about my prediction. But it’s just hard for me to imagine AI being able to do what a really creative human being can do—at least in the near future.

AI will do an awful lot of things but the heavy lifting—the interesting big ideas—will have to come from a human being who understands the way human beings work and what people respond to. Steve Jobs had that ability. Whatever your thoughts about his temper and his brutal nature at times, he really understood people. I’m not convinced AI will understand people in my lifetime. Who knows what happens in the far future.

AI will do an awful lot of things but the heavy lifting—the interesting big ideas—will have to come from a human being who understands the way human beings work and what people respond to.

It’s possible that AI and machine learning has been embraced for efficiency—as opposed to creativity. And AI and machine learning can provide that type of reliable efficiency, even around the edges of creativity—and that’s valuable to a degree. But is it likely to replicate creativity?

I was a musician before I got into advertising. Sometimes you hear that AI has written a song. When you listen to it, it’s not terrible—particularly due to the way music is made today, which is so much easier. But when you go to a concert, for example a pianist who’s been studying their whole life, and you watch that person play. It’s just, wow!

But it’s also quite worrying sometimes when you wonder whether that ability will be lost. I’ve given up the highest quality of music for the convenience of MP3s, and I’ve given up super high‑quality photography because it’s just easier to take a picture on my phone—even though that level is getting very high now.

But there is a part of me that worries whether the simple and faster way to make music might mean that in the future fewer people will study it for 20 years, to master an instrument (or something) because they think it’s not worth the effort. I assume there will always the purists. But I do think there is value in learning and practicing the piano or the guitar. So, sadly, there are areas where machine learning is going to start encroaching.

Still, I find it hard to believe that a passionate human being can’t always win in the end when it comes to writing music. It’s about really understanding what people are going to respond to, as opposed to learning some series of rules and applying them like a formula.

So, yeah. I’m still strong for the humans!

Image credits

Ken Segall portrait photography by Doug Schneider

Apple—Australian Homepage, March 2018

Kofola photo sources on Reddit [no photography credit provided]