Ben Johnston—co-founder of venture studio Jopsephmark—discusses the compelling relationship between creativity, innovation, business, risk-taking and exploring the unknown; revealing as many opportunities as it does challenges. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #8, which focused on the theme ‘Change’.

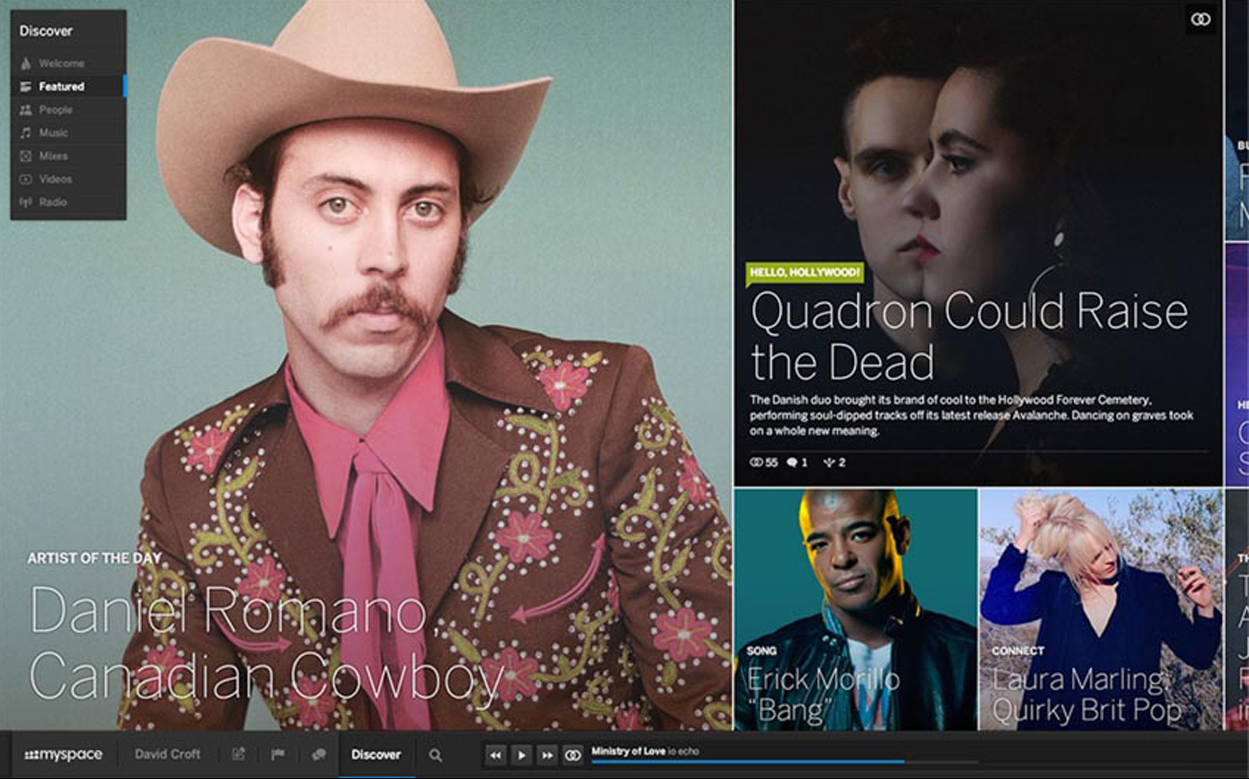

Kevin Finn: Many design businesses and entrepreneurs would kill or die for a taste of some of Josephmark’s (JM) success—from Twitter acquiring your We Are Hunted music platform; to fending off four large international design studios to win the MySpace rebrand by using an unconventional response to the tender; to partnering with Red Bull and various other brands to launch a string of successful initiatives; through to working with South America’s richest entrepreneur, among many others. At the same time, you’ve maintained a relatively small team. What challenges has this brought in retaining a sense of control around the size of the team, while also grappling with the need to scale the business?

Ben Johnston: [Laughing] So, Josephmark is 12 years [circa 2018] old and it’s had an organic upbringing and growth. I founded JM after dropping out of university. I didn’t have a business background, but I had fairly solid creative background, which was intertwined with my Mum being a science teacher. This exposed me to science and mathematics.

I mention that particular part of the story because it relates to my creative journey, and JM’s journey. I wasn’t a design nerd at university but I was surrounded by creativity, so I started a design agency. There was no expectation but I think through its growth we’ve always been driven by a curiosity to just do amazing work, find amazing people. It might sound semi-clichéd to say this, but that approach—that mentality—is very much the DNA of the business.

I guess that has lead us on a journey, which has been quite fortunate, considering the people we’ve been able to work with and being in a relatively small city [Brisbane] in sunny Australia, while being able to establish an international presence.

That background probably explains why it’s been an unconventional journey, if you compare it with what we might understand to be the traditional studio.

Yes, very much so. I refer to it as being like an optimistic naivety, which has resulted in us not knowing the boundaries at any given point in time. As we’ve matured we’ve tried to deliberately maintain that approach. Whether or not that means looking at a design problem through—what is deemed to be—an international design agency, we are very clear about avoiding saying: “OK, we just fit into that particular box.”

On the team front, we have small teams, which we’ve grown like a family operation. So there’s the curiosity—and the talent that comes with the design problems we seek. But then it’s also just about working with good people. We’ve currently got 35 people across the three main [geographic] locations. Of course, that brings its own challenges, because it’s a relatively small team and we try to keep a tight culture across the seas.

But you also need to maintain capacity to respond to the project needs, because a lot of the projects you’re involved with are quite complex…

Yeah. It’s complex on a couple of different levels: one level of complexity might be put in a bucket we could call technical complexity. Another might be design complexity, categorised as a ‘hard challenge’ or problem to solve, all the way through to many of the domains we find ourselves in, where we have no clear brief in terms of what the endpoint might be. That’s the complexity of engagement—working with a partner and having to build trust, literally venturing into the unknown together to arrive at an outcome. That’s speculative complexity.

Given how JM started as a design practice, which is largely focused on digital, it’s always had an entrepreneurial streak. From the outset you very quickly developed a tight business ecosystem across multiple sectors generating various revenue streams. But my impression is this was driven more from—as you said earlier—personal interest, personal curiosity in those particular areas, as opposed to just business pursuits. However, in recent years JM has focused on a series of deliberate and significant venture-based initiatives, which have resulted in some considerable achievements. What instigated this deliberate change of approach?

You’re right. Over the span of JM as a design agency we’ve undertaken over 25 other significant initiatives. Some of those have gone on to be fully formed creative agencies in their own right. Some have built their own lives. Others are digital products, which have been acquired by significant entities.

In the design field, the traditional approach is getting the full brief and then understanding that context to better solve the problem. But our curiosity means that we’ve started looking at the patterns around what initially attracted us to that particular problem or area. We then dissect where the idea came from. In fact, we often get asked: “Where do you get your ideas from?” It’s been an interesting journey—creating a process, understanding it, the landscapes, the context and the pattern recognition that leads to the idea, which then becomes the venture. [Laughing]

Is it more a case of creating a process around the intuition that gets you to the outcome?

Effectively, yes. On one hand, it’s research, but in this digital age it’s really about understanding how to read the patterns and then assessing how to draw parallels in those patterns which underpin new initiatives. We use some of that experience with clients and partners on entirely new initiatives, but which require a mind-set without boundaries or an endpoint. We may not even end up with an idea when we stop, but it’s just an area that we want to continue focusing on and, out of that, something is usually born.

That venture-based approach takes considerable courage, resources, and funding. But do you see this approach as a future model for design practices to adopt generally, whether they are large or small?

It definitely does take courage. [Laughs] But that’s in our DNA, so it’s never really been a question. I think we were always going to end up in this place. I can’t compare JM with other practices, because we don’t come from that formal, traditional design business point of view. But given our 12 year history, I can definitely say that we are more excited than ever about what we do.

I feel we’re really blessed to have been able to start our own ventures, and the work, and all of that, because these experiences with the team and the scenarios that have brought us to this place have been amazing and has created our culture. That radiates out—or transfers—into everything we do within design.

Of course, it’s widely recognized that complete segments of design have been commodified. It’s interesting to look at the fact that AI [Artificial Intelligence] can now design a logo to… an ‘acceptable’ level. [Laughs] But like all things—where we’ve come from, our past, and where were going as designers; the future—it’s not just about looking at the world. It’s about how we look at the world. It’s about breaking outside the context, or the constraints we think limit our craft, and whether that relates to opportunities or problems which exist in the world.

So, I think courage is really in the mentality of creating a sustainable business model around that. And as I referred to before, for us it’s about building trust—in ourselves, to give us the confidence to explore the unknown, but also to take someone on a journey where you may not have a map. But you can at least say: “Hey, we’ve got a piece of paper and a pen and we know how to draw a map. So let’s start walking and let’s plot the way.”

It draws to mind a story I once heard, but which I’m not certain of the details. After successfully re‑launching MySpace I believe you were invited into a meeting with some high level executives in L.A. who asked you to do something similar for them. However, in what must have been a surprise to the executives, you confidently declined their offer and instead invited them to collaboratively explore the future of television with JM—to see what it might look like in 10 years. I understand the executives were from CNBC…

Actually, it was a group called Specific Media, which was acquired by Time.

Right! So, when navigating the future, in the way you just outlined, we’re always juggling between risk and reward. How do you reassure your clients and your partners about the benefits of this kind of exploration, and how do you manage expectations? It’s not enough to say: “Trust us!”. So, how do you build that trust?

We did end up doing quite a significant piece of work around the exploration of future TV, so it actually did come to fruition in a round about way.

Did they decline at first and then…?

Well, there was the usual hustle and bustle but we did end up doing that exploration. Some of those executives had been on the MySpace journey with us, so that helped. I guess we might refer to the experience as a translation from the whiteboard in executive rooms—the theoretical and conceptual ideas—into a tangible product, or a tangible vision of the future, which then lead them to what they actually built.

So, to answer part of the question, the work we did underpins the operating system for a lot of smart TVs, like Sony and LG. What was fascinating for us was the realisation that design is actually quite deep in product strategy.

By looking at what’s happening with the future of content, we then asked how does a TV and a TV brand live in a new world where a whole new generation doesn’t see it as a TV, but a screen?

By looking at what’s happening with the future of content, we then asked how does a TV and a TV brand live in a new world where a whole new generation doesn’t see it as a TV, but a screen?

It’s an access point?

It’s an access point! But what’s interesting is, it’s actually the second screen.

[Both laughing]

And there is so much behind all of that. But it also has to consider how content is produced, what we deem as credible entertainment content, from high budget Hollywood feature films through to a YouTube cut video. How does all that interweave into a single narrative experience, and how does that then translate into an interface—an actual tangible design? So lots of fun work. [Laughs] I guess, that’s where we thrive.

So, to the issue of trust; we have experience in this space and we don’t underestimate or overlook the fact we’ve obviously created a brand, or a reputation through JM, which attracts people who are looking to go on an exploration into the unknown.

But, the process we take internally—both in our consulting practice and our venture practice—is quite a scientific process. The nature of birthing a new venture into the world is an optimistic, creative endeavor. You need to have that approach to actually make anything. It’s the very essence of it. But, it’s about a scientific critique and we use a lot of language that is more common in an actual science lab than perhaps in a design studio.

For example, we create hypothesis and then our process is about testing. It’s about optimization and we’re always trying to disprove our hypothesis the whole time. That gives us the confidence, whether it’s in a venture or consultancy, to know we are on a pathway. And at the same time, we’re bringing something new to life, [laughs] something new into the world.

The business world clearly has to develop a whole new set of skills to adapt to this approach. They obviously understand the need for it, but it’s not standard practice for them. That’s one side of the challenge. The other side of the challenge is designers also need new skills. So what do designers need to learn in order to operate in this space? What did you learn over this period of time?

[Sighs] That’s a good question. I was initially going to answer that question with a fundamental observation, especially for new designers: The conversation is still around print verses digital. [Laughs] But that’s not where it’s at. It’s about the actual process of observation and problem‑solving, which is inherent in designers, just like creativity.

The conversation is still around print verses digital. [Laughs] But that’s not where it’s at. It’s about the actual process of observation and problem‑solving, which is inherent in designers, just like creativity.

Still, it can take a while to adjust. For example, if we’re on-boarding a new graduate, they’re extremely excited: “I’ve just got my first full‑time job at a design agency!” Their expectation is they’re going to just produce a beautiful piece of aesthetic. But then we throw them into a hardcore diagnostic meeting talking about business models [laughs] or future mapping. It’s a whole different world, and you can visibly see their discomfort, because it’s unknown. That discomfort remains for about six months until they start to understand it. They realise they do have capacity to work this way. They realise that they might not have the experience, but that they do have the ability to learn rapidly and understand.

That’s interesting because I still think we’re training designers for craft, where inherently they have a specific way of thinking. And it’s that which is required in this space.

Yes, yes. That’s a very articulate way to summarize what I just said. [Laughs] That’s it exactly! But don’t get me wrong: Fundamentally, I think it’s still good to be skilled at your craft but it’s about broader observation and an application of design or design thinking. These fundamental skills come from design.

It doesn’t matter whether your title is designer or CEO, and that’s the beauty of it. Generally, everybody I’ve met is a true designer because once you’re exposed to it, it’s addictive. Your craft might be how you communicate it, but the breadth in which you approach the challenge and where you can go in the creative realm? Well, there’s an addiction. [laughs]

If we consider most of the big tech companies that we’re all familiar with, many of their founders have been designers, or have a significant connection to designers and design. The acceptance of Design Thinking has also elevated the designer to the most exclusive and powerful boardrooms around the world. Would‑be investors clamour for their attention looking for the next big thing. It has significantly changed the potential role of a designer. While that’s fantastic, and it’s addictive, is there a down side to it? Is there a down side to the role of a designer operating in that space?

That’s an interesting question. [Pause] There’s an instant answer to this, because it’s fairly close to us at the moment, and it relates to how it can make you look at the world with a certain awareness and a different perspective. We recently lost a beautiful human—a local—to suicide because of a heightened awareness. She was a designer working in the humanitarian fields. I can only imagine she got to a certain point where it was too much.

That’s a pretty heavy response to put to your question, but as designers our eyes are opened pretty wide to certain things that are happening around the world. It’s possible you’re no longer getting the satisfaction from what might have previously given you satisfaction as a designer. Instead, you’re seeking to solve bigger problems. And when those problems feel like they’re outside your ability to solve or to create positive change, then that can sometimes feel formidable

But there is beauty to it, as well. Unlike someone who has that awareness but doesn’t have those fundamental design skills, designers have a built-in ability to look at that problem and try to instantly think of creative solutions.

Of course, it’s a fairly large claim to say design will save the world, but at a certain point it’s a mixture of awareness and an ability to apply a creative solution to a problem. That is the starting point to change.

Of course, it’s a fairly large claim to say design will save the world, but at a certain point it’s a mixture of awareness and an ability to apply a creative solution to a problem. That is the starting point to change.

There is yet another side to this. In the high‑level space we’re talking about, there’s an additional persona in the mix—the investor. Designers and creative people tend not to be used to working with an investor, nor are we used to talking at that business level. So a down side might be, for example, where an investor can take advantage of a designer because they’re far more aware of the commercial potential…

That’s a good point. Of course, it’s similar for other experts in these types of fields, whether it’s a scientist or a designer, etc. But designers create communication and narrative. A lot of the time it’s our fundamental craft. But, the ability to communicate things that come naturally to us, like those particular instincts, and being able to take someone on a journey, especially someone with an analytical business mind, that’s a challenge. More often than not, there’s a disconnect and it takes a healthy narrative to bridge this.

Essentially, being a designer, or someone within the creative fields, means wearing your heart on your sleeve. And that just makes us—by default—more vulnerable human beings. It means we’re susceptible to being taken advantage of, if someone is intentionally leveraging those aspects, if they have that inclination.

On the positive side, the beauty is that you can build awareness, over time [laughs]. And once you have that awareness and that confidence, by having those conversations you hold a magic‑like secret sauce, a potion that can’t be [laughs]…

Commodified?

Yeah, commodified! As a result, you instantly hold a kind of power in that relationship—and it drives an analytical mind bonkers. [Laughs]

At a deeper level, business leaders are aware they need to understand design’s value. They can sense it but are perhaps unsure what it means or how to adopt it in a practical, tangible way. Are you seeing a shift with business leaders—or even investors—who are either understanding design better or are more trustworthy of a designer by saying: “Just do what you do”?

Yes, but I say that with a caveat. There’s a certain perspective within the people we are working with because of a connection that has been made through a whole bunch of contexts around that interaction…

But what about on the way to getting to that position?

On the way—absolutely! It’s been well documented, especially in the tech scene, where there was an intensity in the early stages—around the early 2000s—it was all about engineers. At a certain point, with the commodification of engineering, it became increasingly more important to have end-customer and end-user empathy. Designers inherently have this and it prompted a move towards designers leading products and building things that were more successful at the end of the day.

We’re now in this really interesting world where it’s becoming a blend of the creative technologist—engineers who understand their craft and can empathize in a way that relates to a design mind, working together to solve an outcome.

We’re now in this really interesting world where it’s becoming a blend of the creative technologist—engineers who understand their craft and can empathize in a way that relates to a design mind, working together to solve an outcome. The solutions of the future, especially in this realm, will be the blending of those two minds and two crafts. And it’s a beautiful thing to watch—sitting together, building something and creating something, bouncing across realms.

In equal measure?

In equal measure, with equal respect and with an outcome that’s greater than those paths is… It gives me goose bumps just talking about it… [Laughs]

You’ve mentioned a few times in this conversation that you are in a very fortuitous position, where JM has created a specific profile, one that attracts a certain kind of client who is looking for that inspiration. But for the most part, my understanding is JM doesn’t promote itself in the traditional sense…

[Laughs]

Yet, you attract these significant projects, clients and partnerships. So how do you achieve that?

Putting aside the obvious ‘word‑of‑mouth’, which is common among most businesses, I guess it’s been our deliberate [laughs] curiosity, which has led us to building ventures and educating ourselves in particular domains. This has given us specific experience with the opportunity to develop outputs that haven’t been constrained by a brief. Because of this, we’ve been identified with clear domain knowledge or leadership in a particular area, resulting in people reaching out, using that as a benchmark. And this probably also goes back to a previous question around trust.

A lot of the work we’ve developed is online. So, when we can point to examples that have been, um…

Successful?

Yes, successful. That inherently builds a trust and shows that we understand business. It shows we understand the objective of a successful business model combined with the success of a designed output or product.

So, along with referrals, those self-initiated project outcomes provide specific exposure, which might be more potent than a traditional business development campaign. Is that an accurate assessment?

I think it would be very hard to run a traditional campaign to find the clients we’re looking for. It’s definitely been the work which, when it’s out in the world, has been able to relate to particular people, to talk to them, and then it’s come full circle back to us.

We moved into the [United] States over half a decade ago on the back of venture work we were doing. We started working with some of the most amazing brands, but we weren’t competing for RFPs [Request For Proposal] or anything. We were invited on projects with very open briefs—along the lines of: “Hey, we wanna do something in this space. Let’s go and build something together.” It was just incredible.

It brings to mind a scenario of a few years ago, where you were involved in a panel discussion around how designers and business owners are working together. One particular comment that you made stood out. When asked who JM’s competitors are, you said: “None. We have no competitors.”

It was a compelling answer—and it was said in a very matter of fact way, without arrogance or ego. Even the facilitator, Ray Labone—who is very familiar with JM—was initially slightly taken aback. Given what you just said, is this still how you see JM? And if so, can you expand further on that position? Do you even remember that comment?

[Laughs] Yes. Yes, I do. [Sighs] I still stand by that comment, as far as how JM operates in the world, where it’s a blend of briefs. Traditional briefs do still come our way but the majority of what we are doing is exploring and looking at these opportunities, these problem domains. There’s a lot of opportunity—and a lot of problem domains in the world.

We look at the full societal spectrum, right across to potentially highly commercial endeavours. So, because we’re not reliant on trying to win work from a competitor we’re forming new pathways. In doing so we look at the influences of competitors operating in those spaces, which becomes part of our assessment process. If the field is too hot, or if there’s too much dominance, we’ve got the ability to change. [Laughs]

To simplify this: is it correct to say the traditional approach is to compete for the present, whereas JM offers an exploration of the future? And competing for the future doesn’t even enter the competitor scenario, because we don’t know what that future looks like yet.

That’s a good way to simplify it.

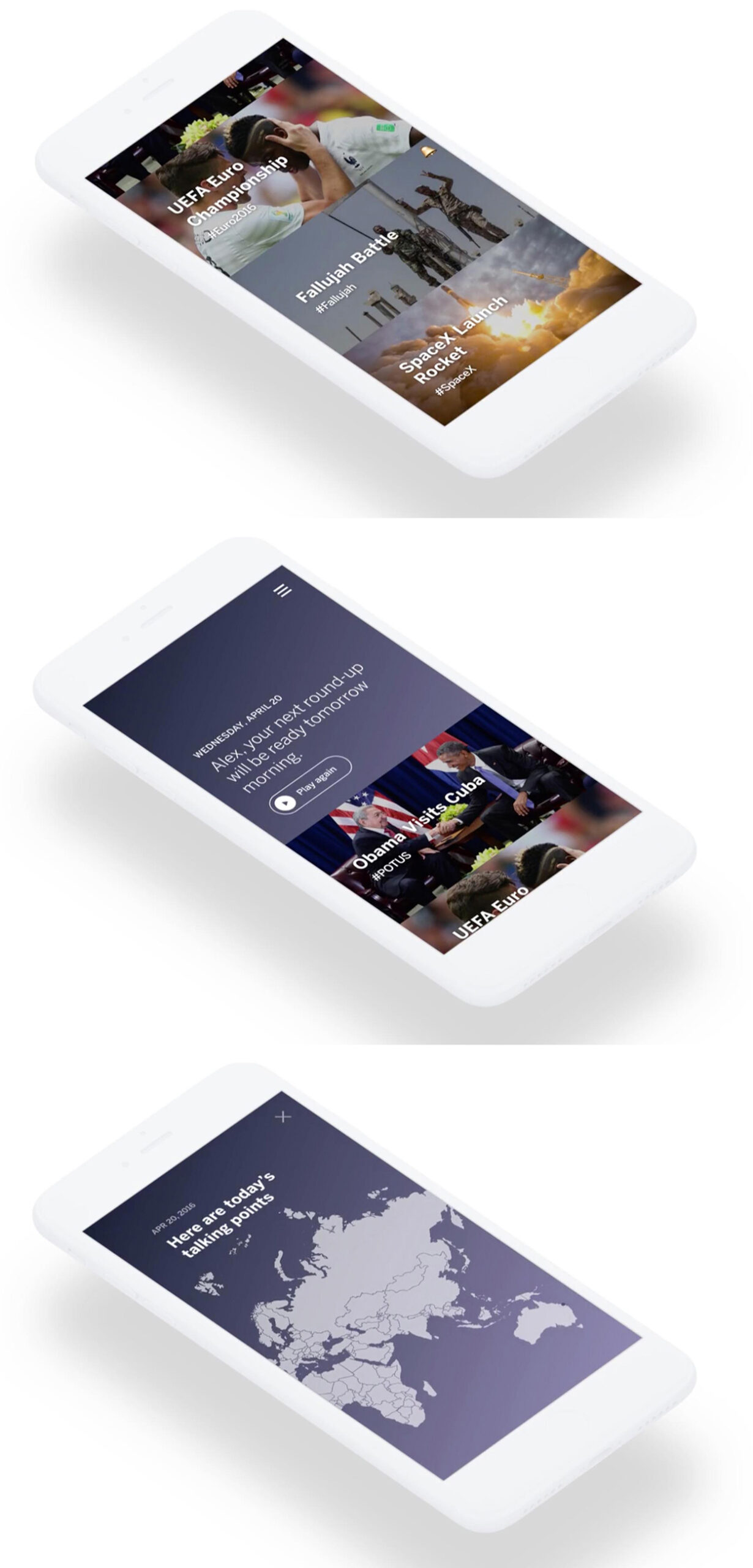

Hash is one of JM’s recent initiatives, an aggregated news app, which has been incredibly well received by consumers, critics, and media alike. So much so, I recall one media comment suggesting that Hash is what Twitter needs to be, or what Twitter is trying to be.

Yes.

So what’s involved in developing a venture like this? We’ve talked about exploring the future, but in tangible terms, what’s involved in this exploration, and how has Hash impacted the business.

Part of our process is looking into the future—anticipating the future. We look at different areas of opportunity, which could either be far-reaching or quite specific. Hash was born out of a combination of both—a will and a desire to explore what the future of media and news looks like in an ever‑connected world, with an increasingly collected and united consciousness. We considered what type of situation or platform could provide a non‑biased centralized news source to the world’s conversation. Combining this with our history with Twitter we also understood that Twitter is an immensely wealthy source of information and conversation.

Hash was born out of a combination of both—a will and a desire to explore what the future of media and news looks like in an ever‑connected world, with an increasingly collected and united consciousness.

It’s quite a sophisticated system, but simple in its interface so that the average person can fully comprehend and participate in the conversations happening on Twitter. It’s really a combination of those two insights, like bringing together a much more user‑friendly interface with all of the major news topics being shared on Twitter, which represents a non‑biased conversation—the global conversation.

But we then looked beyond the Twitter-sphere, aggregating and sourcing content of conversations from around the world through different sources. The result was Hash. And it’s been globally recognized, and has had a great response.

It’s an interesting position that we find ourselves in, because we’ve had a taste of what we feel the future of news could look like. And that’s a much larger mandate than just Twitter. We’re also asking ourselves: “Do we want to continue?” And of course, we do. So we’re continuing on that mission—which is being a piece in the puzzle of what will be the future of news.

It’s interesting: Twitter is relatively simple—[at the time of this interview] limited to 140 characters. And they’ve now embraced video. But, they didn’t make the leap—matching their current platform with their new business strategy of wanting to become a news media player, or at least leveraging the news more. Of course it’s easier with hindsight, but if we consider Hash, it’s, sort of the next logical step. But they hadn’t joined those dots. Do you have any insight as to why that might be the case?

We do, and it’s probably a combination of the fact Twitter has exploded to a certain size, as well as the inherent issues which come with a larger organization. I can only assume there are ongoing pressures in the organization and with shareholders, which can result in sometimes overlooking the simple things.

But what’s beautiful for us is that it’s provided an opportunity for us to really go deep in this space. So, the conversations that happen in the Twitter-sphere, especially around real‑time events, is just second to none. It’s never existed before and doesn’t exist on any other platform to the same width and breadth. And yet, it’s extremely hard to participate in that conversation, unless you’re an advanced Twitter user.

So, Hash is trying to create that accessibility, that participation. But, we’re also exploring how narratives and stories are being generated and going on around the world, from breaking news, to evolving stories, to longer narratives, and then to local or hyper‑local. We’re looking at how to bridge that in a national and global way. It’s a further exploration of a non‑biased news source, but opening up the system to capture the full spectrum of someone’s news requirements. And that gets into extremely interesting spaces, blending the role of the journalist with the emerging role of the citizen journalist, right through to the ability for machines to write news content.

That gets into extremely interesting spaces, blending the role of the journalist with the emerging role of the citizen journalist, right through to the ability for machines to write news content.

So, Hash Version 3.0, [ released in 2017], is very much focused on the intersection of those three facets. We find ourselves not only grappling with questions about what the future of news and the future of media might be. It’s also about those social questions, about how, ultimately, building systems that are automating a large degree of news content is going to influence and affect the role of the journalist and whether it’s inevitably going to be part of that future puzzle. Either way, this means the current role of a journalist is going to change.

Of course, journalism is not necessarily going to end but it’s definitely going to evolve in this new world. So we have a lot of conversations internally about things like this and the social responsibility we have as designers, building these new platforms, which are going to impact the livelihoods of individuals and people’s work life in profound ways—and not necessarily always positively…

Of course we now have a new phenomenon—the rise of fake news. This is becoming a real issue because the general news consumer isn’t going very far into deciphering what is fake and what is real. For many, ‘news’ content is taken at surface value and it can be quite taxing to try and dig a little deeper to try and decipher if it’s fake or not. So where does Hash sit in this sphere?

That’s an extremely good point to raise. The effects of algorithmic social bubbles and social networks, especially in terms of the recent US presidential campaign, is now a well documented issue, particularly around the kinds of discussions that were going on with key leadership in the social networks because they could see what was happening.

But I think it was the right call for them to make—to not necessarily interfere with the algorithms and seek to create vices that were more aligned with their own views. However, what’s happened since the outcome of the US election is that those platforms, particularly Facebook, have changed and modified their algorithms to identify and deprioritise ‘fake news’ sites. And that’s the same sort of approach and dialog that we’re having around Hash.

If you imagine the algorithm is an aggregation algorithm so, on the first level it treats everybody the same. That’s how you create a non‑bias around a news issue. But the beauty of algorithms is they run by a set of rules so we can start to influence those rules, or look at additional information around these news sources and understand whether it’s a news source with a level of credibility or a news source that’s got a certain bias, due to the influences on that news source. So, that means we can prioritize certain news. But it’s a slippery slope, which raises all sorts of questions around biases.

It strikes me that it’s going to be very hard in the future to operate with absolute neutrality in this space.

It will! However, the beauty of ‘the future’ is there’s more and more ways of attaching metadata, especially to virtual assets, and everything leaves some sort of data trail that can be measured, monitored and compared and then put into very complex patterns. So, there’s a level of transparency which can be gained from that.

It’s more a design decision around how that is portrayed. I think that’s where the question will ultimately lie because, for example, Facebook will have so much information around the influences on an individual news article—before it even hits your feed. That’s why we get these social bubbles occurring on those types of social networks. And, they can ultimately tell you whether that piece of news is fake or not.

Is it their role to do that? Well, that’s another question.

[Laughs] Shifting gears slightly, the importance of operating in the digital space—or having a digital first strategy—has been universally accepted for a long time now, almost at the expense of everything else. Yet, more recently, we’re seeing a combination of online and offline approaches from relatively small projects, up to larger, more complex initiatives like the launch of Amazon Go and, to a degree, Uber. Clearly, it seems at the moment that an ‘either/or’ approach is being challenged. So, aside from the Internet Of Things, what’s your prediction for an integrated digital and physical future?

We’re at the start of new digital evolutions, one of them being the rapid infiltration of artificial intelligence, whether that’s artificial like IOI [Input/Output interfaces] connected devices or whether IOI will become a baseline to the virtual world.

And then there’s the more pointed prediction around the disappearance of the screen as we know it. So, we’re still in this transition and it’s going to be interesting looking back in 10 years’ time. Today’s headsets might feel like how we look at a Nokia 3210 now. [Laughs] But these highly immersive blended realities are starting to forge the way and once the hardware evolves to the point where, for example, phones become just pieces of glass and then evolve into a situation where we don’t necessarily use a fixed device—where everything becomes an interface—then that’s what we’ve got to look forward to over the next decade. And it just presents a whole new gamut of interesting usability situations and scenarios. For designers, it’s like finding a whole new colour palette in the colour spectrum.

[Laughter] It’s just going to be really interesting. And this will ultimately have an affect on business models, heralding disruption across the board.

You mentioned “disruption”, which brings me to my next question. We hear the terms innovation and disruption everywhere. It’s become default business jargon. So much so, there’s a perception that businesses are innovating every other week, which doesn’t actually happen. As a result, these words are becoming rather meaningless. What’s your definition of innovation or disruption?

It’s an interesting question. Based on the first part of your point, around how a lot of these terms are increasingly and rapidly being adopted, there’s a proliferation of activity—and then they’re discarded. [Laughs] That recently happened to Pebble [smartwatch]. Terms like design thinking and, as you said, disruption and innovation, it doesn’t feel like they have long life cycles. But the core meaning behind all of these ‘buzzwords’ rings very true.

Terms like design thinking and, as you said, disruption and innovation, it doesn’t feel like they have long life cycles. But the core meaning behind all of these ‘buzzwords’ rings very true.

I find myself witnessing others talking about these concepts and almost being conscious not to use that clichéd language [laughter], because it’s thrown around so much—like it can be bought and picked up with your cornflakes in the morning. Yet, we’re seeing more innovation than ever, although it’s still very contained; it’s still not affecting the riches of our society, or our corporate structures, or our government systems in the way that it fully could. But I think there is an opportunity in that. However, there is also a word of caution because the language has almost become a constraint, as though it’s more conceptual and theoretical than actual or tangible.

We use the terminology quite freely and confidently because it’s based on actions. The language has to be followed up with execution and outcomes, and this helps us in talking about these types of concepts with a level of credibility.

Conversations I’ve been having in this space—challenging how people use the words innovation or disruption—there seems to be two sides to the debate.

On the one hand, which is where I generally land, it’s seen that innovation is a game changer. It’s a pioneering direction towards a new or alternative future, something that challenges everything currently in a category or a market, something that shows there’s another way to do it, a better way to do it, or a more efficient way to do it.

The other side of the debate—relating to the word innovation, in particular—is the argument that innovation can happen on smaller scales within a business or an organization; that it can happen continually in an iterative way as a means to keep improving on something.

Dan Roosegaarde—one of our contributors to Open Manifesto#8—suggests that: “Making something less bad isn’t innovating.” He takes the view that innovation really must be a game changer. Where are you finding the conversation in the circles you’re operating in?

That’s an interesting question. I see innovation as both sides of the debate you’ve described. Game‑changing innovation comes from experienced domain language and a creative mind that has the freedom, space, and confidence to assess a particular ecosystem in a specific landscape. This provides a level of assurance or confidence about suggesting a new concept or idea applied to a pre‑existing format.

To achieve this—to execute on those big ideas—is about balancing that vision (and we were referring to mapping earlier), yet trying to find the hidden valley in order to know where the vision’s going. It’s a step‑by‑step process.

An example of a familiar large innovative, disruptive company in the last decade is Uber. It’s generally accepted that they’re a fairly innovative company. But the steps to get there required a whole bunch of smaller innovations and an understanding of a customer journey before they could build trust in a whole new system and business model. So, it’s neither one or the other. They are two levels of innovation together.

But in our world, the credibility comes with execution, especially, when you’re going into the unknown. It requires a format, a mindset and a nimble culture. It’s all in the approach and the mindset. Everybody needs to be comfortable and confident, because everyone involved is continually taking these small steps into the unknown. To me that’s innovation. And the only way that you confidently do that this is if you’ve got a clear vision, which then eventually becomes the big innovation.

It’s all in the approach and the mindset. Everybody needs to be comfortable and confident, because everyone involved is continually taking these small steps into the unknown. To me that’s innovation.

It strikes me that, if you create a culture of innovative thinking, a way to adopt small‑step improvements, this may eventually lead to an innovation as an output, but at a later stage—as an aggregate of this small‑step iterative thinking. The trap I’m seeing, though, is that organizations and businesses tend to think innovation must be the output, that it must be the end thing, and that it can happen almost overnight or next week. Whereas, what it requires—as you say—is this aggregated approach to thinking at different stages towards a singular objective. And then, over time, perhaps you will disrupt or innovate. Is that a good assessment of your view?

Yes, that’s a good summary. And it relates to something you mentioned before. We associate innovation with making something better—that it’s a progression, it’s an evolution, and that ultimately, innovation occurs when the right foundations are in place for it to occur, whether that’s in a culture or in the mind-set of an individual.

These foundations require a level of understanding and context—so it’s not blind or accidental innovation. It also needs confidence and freedom. So I think that the framework for innovation starts with these foundations. The rest is the play space. [Laughs]

Of course, design is at the heart of this innovation and disruption movement. We see design and designers championing this space and being active within it on a daily basis. But design is also open to the same influences. So, how do you see the future of design being disrupted?

[Laughs] Designers are perfectly situated to be comfortable in this space—and to be confident in it—because of our mindset and because we’ve been trained. So, the disruption for design will occur in our fundamental crafts. That’s where we’ll see it emerge, that’s where it will be most apparent.

The disruption for design will occur in our fundamental crafts. That’s where we’ll see it emerge, that’s where it will be most apparent.

The best conditions for design innovation come with certain constraints so I think it’ll be important to have an open mind and to be able to just accept that we will have more constraints in core aspects of design as a craft. But that provides opportunity at the other end, to continue evolving within spaces that have more constraints, but potentially have more opportunity. As a discipline, and at the core of what we’re trained to do and how we look at the world, designers are in a very good position to be among the most prominent ringleaders of how we’ll see—and how we’ll realise—the future.

Going back to an earlier comment you made about the craft of design we talked generally, about how design education is still largely focused on craft. Yet a major disruption that our discipline will face is coming from AI [artificial intelligence] and automation. As you mentioned, logos can get designed by AI right now at an ‘acceptable’ level. But that’s only going to get better. So, do you see the AI space and automation being a big disrupter for design in its current form?

I think it’s going to disrupt through the commodification of some of those elements of design. As a result, designers will become the facilitators and articulators of craft. There’s a process and there’s a pattern, and as you get more experience, designers are able to see more of that pattern and this ultimately influences you in a lot of ways in how you design an app—or whatever form it takes.

Fundamentally, AI and machines aren’t creative. They work within boundaries. They are very good seeing and deciphering patterns. If that output has enough constraints, or the result has got enough constraints applied to it, then a machine can do that, or will be able to facilitate that process. It will be interesting to see how that affects things.

What I think is beautiful about it, though, is a blending of a couple of the questions we’ve been talking about. In an ever increasing digital world, as humans we start to respect and appreciate the physical world more, and elements of tradition and good design within the physical realm become more valuable. That’s only going to become stronger.

A simplistic example would be, as graphic designers we’ve started seeing the resurgence of letterpress; and musicians are seeing the resurgence of vinyl. All of this is a culmination of the path we’ve been on, in terms of innovation and a fascination with digital and high‑tech. And then, 10‑20 years later, while on that pathway we’re beginning to say: “Whoa, hey.” [Laughs]

We’re saying: “Yes, I want that. It brings me efficiency and access and a level of beauty.” But it’s a lack of the tangible, or just the lack of depth derived from technologically driven processes or experiences and what these evoke, which is drawing us back to an appreciation of the traditional and the tactile.

It’s a lack of the tangible, or just the lack of depth derived from technologically driven processes or experiences and what these evoke, which is drawing us back to an appreciation of the traditional and the tactile.

I think you’re right. It’s not an ‘either/or’ situation any more. Some of the future challenges and opportunities I see for designers is that we need to be far more articulate and clear about our value versus our output. Machine Learning and AI are going to automate some things, and there is a value to that. But there is another deeper level of value that a designer can offer. And it’s on us to be able to express that to clients, to businesses, to society.

Absolutely! And it’s easy to be a bit doom and gloom about it all, but we see it as an opportunity. It’s not a short‑term opportunity, in the sense of designing an automated process to disrupt a particular market. It’s more about the opportunity which this technological evolution brings to widen your toolkit [laughs], to be able to expand and experience what you’re ultimately facilitating. So it’s definitely going to be interesting.

But I think you’re right. It will be a lot to do with how we look at these aspects as designers. If we consider the last decade, where we’ve seen a sharp rise in globalization, commodification of certain aspects of graphic design through outsourcing sites, and all of that. Well you’re right. It’s all output‑driven and for a large segment of the population that’s their level of understanding. That’s going to satisfy a particular need.

But you can see, and again it’s been widely documented, the potential fear that obviously surrounds these kinds of evolutions. Designers simply need to approach it by saying: “That’s just another constraint.” Because it’s not going to stop. It’s about understanding your value, and the values you mentioned within the process that is ‘design’—and then evolving what we do.

I want to pick up on something you said a moment ago, about the tactile and tangible versus the digital and technical. JM are largely focused in the digital space, but you and your wife Jessica Huddart (JM CEO) have also embarked on a farming initiative. Can you expand on your motivations for exploring farming and food production?

Absolutely. We all spend a lot of time in a virtual realm. For example, I can be in this studio on an evening, and through a smartphone and a food delivery service, I am two clicks away from having a well‑cooked meal on my table within 20 minutes. That sort of efficiency, and that type of experience, means even though I may have some appreciation around the output in terms of that taste of food [laughs], we were finding ourselves becoming more and more disconnected with the narrative and the appreciation around the process to get that meal on the plate.

So, Falls Farm was really our curiosity, our will to seek out and—in a lot of ways—ground ourselves. We have been fortunate enough to be able purchase a small pixel on this planet, in a very fertile location on the Sunshine Coast; to start educating ourselves and explore food production. Ultimately, it was this curiosity, a desire to understand the level of inputs, energy, and time it takes grow a carrot. So, when you eat that carrot, we can understand all the narrative and that appreciation is bundled up in that experience.

Now it’s a fully‑fledged organic seasonal vegetable farm, a small crops farm. It supplies a bunch of restaurants throughout southeast Queensland. But there’s been a lot of additional learning from that whole process, too, creating closed loop systems with restaurants, and then all the education we’ve been observing through the process.

Ultimately, the wish is to not just have this for ourselves, but to really be able to use it as an educational base to influence people’s understanding and perception around food, and an accessibility to good quality food. It’s been an extremely exciting and satisfying journey so far. It has done amazing things for our work life, as well, just in the sense that I grew up in the country and love the wide‑open spaces, the fresh air and the lack of ambient noise. It’s just so cleansing. Your thinking is broader and goes wandering into a whole realm of new places. I guess we were starting to feel a little bit confined in how we were living over the last 10 years or so.

This whole conversation has essentially been about exploring the future. A vital pillar of the future will definitely be food production. So while all the things we just discussed are very personal, very down‑to‑earth, very tactile and non‑digital, it’s still consistent with your personal philosophy and that of JM—exploring the future. So, is the farm another aspect of this? Is it subconscious, or is it deliberately conscious?

[Laughs] There is definitely an evolving vision there. And we understood that a little when we started. But we do see these two worlds will ultimately collide at some point in the future. We’ve been talking about automation and machine‑learning and it’s interesting to begin seeing how that can affect farming. It’s AgriTech on a large scale. Technology is infiltrating large‑scale farming practices in many different ways.

I think the solution for global food requirements—and it comes back to the innovation question—is going to involve some pretty radical rethinking around the systems that we’ve all been using.

I think the solution for global food requirements—and it comes back to the innovation question—is going to involve some pretty radical rethinking around the systems that we’ve all been using.

Obviously, this will also involve the transportation issue. But it’s also the systems, and there are some really cool prototypes coming out. A recent one is called FarmBot.

You may have seen it but, basically it’s a robotic arm you can have in your home garden or veggie plot, and it can test the soil to monitor nutrients and moisture. But it can also plant the actual seeds for you, monitor the growth of the plants, and understand how much sunlight that particular garden is getting. But it won’t pick the veggies for you, [laughs]…

Not yet! [Laughing]

It will grow the whole thing for you! The interesting part is, the companies have made the plans open source, so you can actually print and build this device at home. I think that’s just such an amazing example of where we are potentially going with this level of intelligence, which can be built into a really simple consumer robot, ultimately resulting in a tangible carrot [laughs]. And grown in your own backyard!

It’s pretty amazing. To wrap up, what does the future of JM look like? What changes do you anticipate, if any?

We’re moving more and more into the venture lab model, even though it’s been our approach for about five years now.

We currently do this with clients and also within our own venture portfolio. We’re just continuing to build expertise and fostering a culture of innovation within a process to allow us to continue investigating new horizons as we see them appearing.

Ultimately, we’re driven by this sort of curiosity. But as a business, we’re creating those foundations, which allow us to work in interesting areas where we can have a positive impact.

Of course, there’s also the potential commercial impact, which we can also see. But it’s much larger than that for us. Working in a client-supplier relationship will have its own sort of gripes and interesting stories about how those relationships ultimately unfold. The beauty is when you find the perfect client where you get to embark on a journey and explore outputs you can create.

So, we’re moving more and more into this area where there is less requirement around that sort of client definition—or lack of definition [laughs] to present the opportunity. Increasingly, it’s about being able to wander in the wild and pick interesting people and interesting things to explore together.

This might sound glib—and I don’t want it to sound like a promotional comment for JM—but, it strikes me that what underpins all of this, what’s behind the portfolio and the investment initiatives, is a genuine sense that you’re literally investing in the future.

Yeah. That’s exactly it. And it’s very current; it’s a very topical conversation, especially at the moment given the year that has just been [2016]. The global upsets, whether political, or terrorism, or just general unrest; I think as we’re seeing this through the lens of rapidly increasing technology we’ve already portrayed certain visions of our future in Sci‑Fi movies, for example, which suggest a negative impact the human species. But it’s in our collective consciousness.

It’s bigger than an agency; it’s bigger than a client; it’s bigger than a venture. It is about exploring the future—the future of the planet. That’s a pretty cool place to wake up to in the morning—and to be able to spend our time there.

At the risk of sounding clichéd, in all of those movies there are pockets of individuals or groups of people with a certain awareness, who sits outside the system—where they can observe. They’re often referred to as rebels, or the rebellion front, or a sort of semi-outcast group. I’m not saying that’s what we’re driving to be. But we firmly believe that design has a role in saving the future, as clichéd as that might sound. Perhaps a better way to think of it is design has a role in making the future better.

To ensure that impact designers do need to change the paradigm a little bit, in terms of how we work and how we spend our time, how we create sustainability—in both the commercial aspects as much as in wellbeing. But it’s exciting. There’s nothing else we want to be doing [laughs], no other path we ultimately see ourselves pursuing.

It’s bigger than an agency; it’s bigger than a client; it’s bigger than a venture. It is about exploring the future—the future of the planet. That’s a pretty cool place to wake up to in the morning—and to be able to spend our time there.

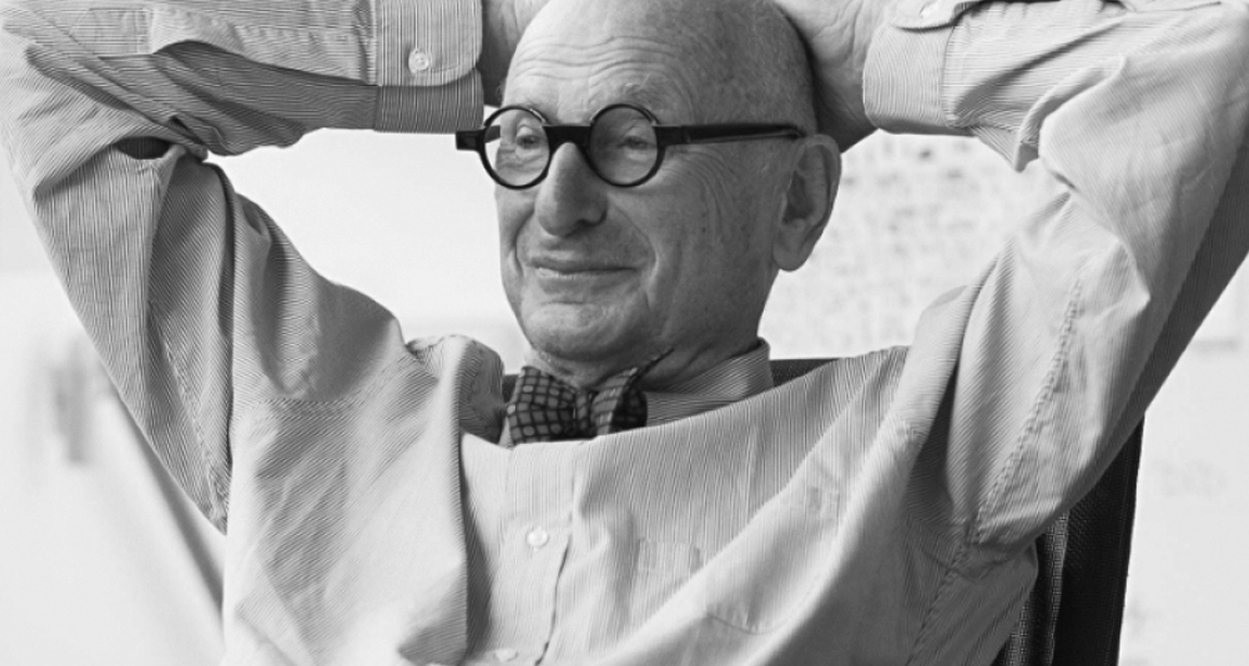

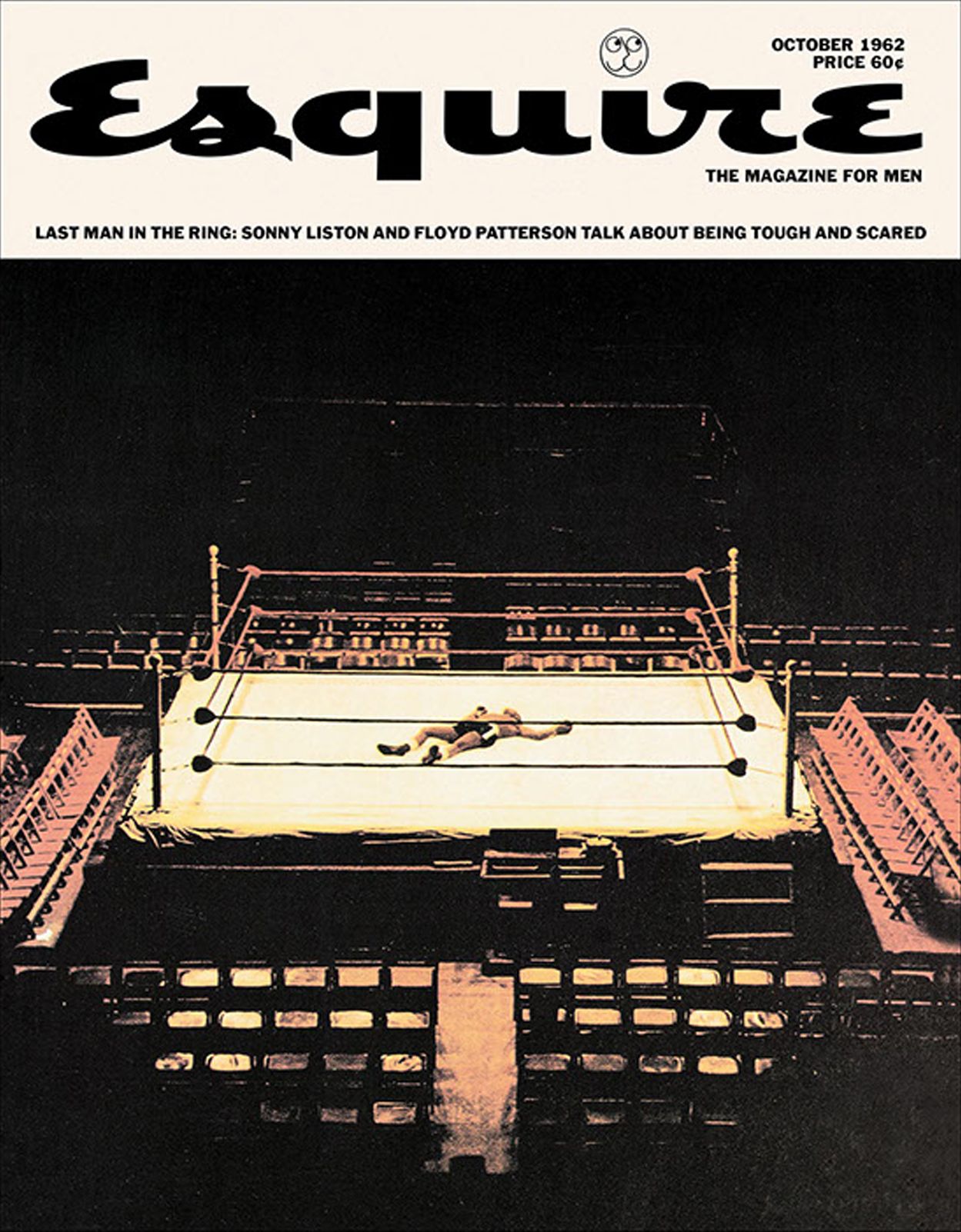

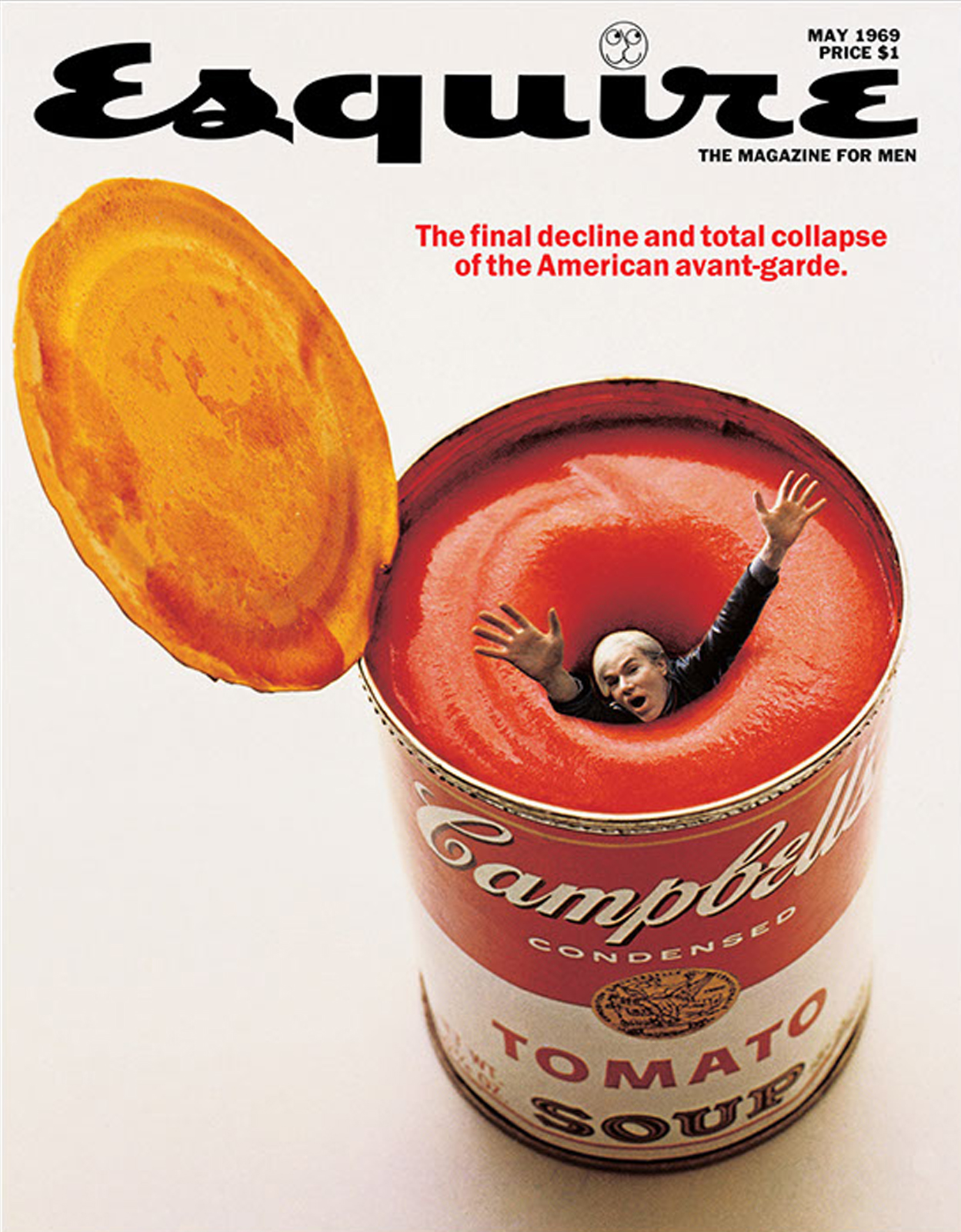

Image Credits:

Ben Johnston portrait provided by Ben Johnston

MySpace sourced from Josephmark website

Hash images sourced from Josephmark website

Falls Farm sourced from Falls Farm website