Legendary Art Director/Designer George Lois talks about his politics, discusses his unique relationship with Esquire editor Harold Hayes, reveals how Paul Rand influenced Bill Bernbach and debunks the Mad Men TV series. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #6, which focused on the theme ‘Myth’. (Sadly, George passed away in 2022, aged 91.)

Note: This interview took place in 2011 and refers to specifics from that time.

Kevin Finn: I’d like to start with a recent topic. Last week, millions of people around the world welcomed the death of a symbol—Osama Bin Laden. However, amid all the celebrations there’s been a debate around whether capturing Bin Laden, rather than killing him, would have provided the opportunity to demystify and weaken his influence. In your opinion, has killing Bin Laden inadvertently strengthened the symbol and created an Islamist-style Che Guevara equivalent?

George Lois: Well, first I should say a little bit about what I’ve always believed in. I’m anti‑war from day one. I’m a left‑winger. People in America are afraid to admit they’re liberals. I’m not afraid to admit I’m a left‑winger and I don’t give a shit what anybody thinks.

I was forced to fight in the Korean War and I understood first hand the stupidity of the war. That was one of the first of our stupid wars. Actually, we were defending a racist, a fascist premier of South Korea. I mean, people still think the Korean War might have been a good war. As for Vietnam, I think it was kind of a war/genocide.

I went to Korea on a troop ship with 5,000 guys. We went to Yokohama port, Japan, before we continued on to Korea. There were 5,000 guys leaning over the edge of the boat looking down at the people on the port. They were a completely different culture. There were a lot of women dock workers. They were all walking in clogs, etc. And 4,900 of the 5,000 guys were yelling, “Yay, yay, socha hachi. Hey, hey, gooks,” and they were doing slant‑eyes, etc. I realized—though I’ve always understood—that I was living in a racist society.

In fact, when I just turned 20 I took basic training in Camp Gordon [now called Fort Eisenhower], Augusta, Georgia, in the middle of the Jim Crow Deep South. Colored drinking fountains, white drinking fountains… racism all over. So I understood racism back then, and I understood wars that we were involved in were stupid, including the Iraq War.

But, if you ask me about Obama and whether we should have done what we did, you bet your ass. I changed from being a guy against war and violence to a guy that said, “Kill that motherfucker.” I mean, he came down here and he did what he did to America. I don’t believe we did anything wrong. I think Obama did everything exactly right. I’m with the Navy Seals. I fought alongside the Navy Seals when I was in Korea.

So, as to whether America did the right thing, and whether Obama did the right thing, I’m with him 1,000 percent. Am I with him about his decision a year and a half ago to increase the war in Afghanistan? I thought he was absolutely wrong. I’m still furious at him. But I’m still with him because I think he’s 1,000 percent, 2,000 percent better than anybody else we could have had. I think we got the right President at the right time. But I’m still furious that we’re not the hell out of Afghanistan.

But your specific question was about Osama Bin Laden. He should rot in motherfucking hell. I have a very personal hatred of him above and beyond of what he did because my best friend was a football player, a great buddy of mine by the name of Dick Lynch. His 28‑year‑old son was in the first building at 9/11… which killed him. His father and I went down to ground zero the next day and we were allowed to go all the way through because he was a football player. He was from Irish heritage. He played with Notre Dame.

All the cops and all the firemen were Irish and they all know him and they let us go all the way down right into ground zero. We had to look through barrels of arms and legs that they’d found just to try to identify him. If I could have, I would have gone to Afghanistan as a Lone Wolf, found Bin Laden and killed him myself. I would have slit his throat. I ain’t got no problems with killing Osama, if that’s the question.

Obama said it was justice, and I say it’s justice and revenge. I mean I’m a macho son-of-a-bitch. And at the same time I’m very much against wars because I think it puts young men and women in harm’s way. It’s not the direction our country needs to go in. For many years, our male, conservative sons-of-bitches, Republican goddamn leaders have taken us there. But Obama getting Osama Bin Laden was just masterful, and I love the President for doing it.

It’s interesting, Bin Laden, and Al Qaeda, and groups like that have really understood how ‘sensational terrorism’ can use news media as a powerful promotional tool. It’s probably not too dissimilar to the Vietnam War, which was the first televised war, where the American establishment was trying to tell the country “we’re winning the war, here it is televised, we’re doing so well.” They were using television as a sensational tool, which ultimately backfired…

Oh sure, they were using it. I mean it’s amazing that they were showing plenty of goddamned combat on American television… You know, you would think the opposite. I mean, George W. Bush—that son-of-a-bitch— wouldn’t allow any photographs of American coffins returning to America. I fought in a war where we lost over 30,000 men, as many men in three years as Vietnam lost in six years. The Korean War was twice as vicious as Vietnam, but nobody really understands that. I think I was the only guy in the army that knew it was a bullshit war.

So, I’m a big‑mouthed Lefty. I mean, if you look at my Esquire covers… You can smell my politics.

I’m a big‑mouthed Lefty. I mean, if you look at my Esquire covers… You can smell my politics.

Yes, your political and social views are seemingly inseparable in much of your work, particularly of that era— the ‘60s and ‘70s. Was that something you fought to include, or was it the culture of the time, which welcomed that kind of approach?

No, I lost a lot of business by showing who I am. I really lost a lot, even later than that, in ‘75 when I got Muhammad Ali to join me and start raising hell about Rubin Hurricane Carter, who was absolutely screwed and had already been in jail for 15 years or so for supposedly killing three white people.

I got dozens of celebrities to back us, and I was raising hell with getting Rupert Hurricane Carter out of jail. He was being depicted as this crazed “nigger.” I lost two big accounts because of it. One client called me in and said, “Stop working for the nigger.” I said, “Well, I’m not gonna stop working for him because the guy’s innocent.” He said, “Lois, I just told you—if you don’t stop working for the nigger, you’re fired.” I said, “Well, I guess I’m fired—so go fuck yourself.”

One client called me in and said, “Stop working for the nigger.” I said, “Well, I’m not gonna stop working for him because the guy’s innocent.” He said, “Lois, I just told you—if you don’t stop working for the nigger, you’re fired.” I said, “Well, I guess I’m fired—so go fuck yourself.”

So I lost the client, who at that time was my biggest account. It was a six million dollar account and I walked out. I went back and told everybody in the agency. You know, when you tell people that you lost a big account, everybody’s scared shitless that they might get fired. Right? I remember I called everybody in, and there was like 60 people. I told them the story: “I told the guy to go fuck himself so the account is gone.” But, you know, 60 people gave me a standing ovation. How’s that for good people? People who understood what I was about; somehow I picked the kind of people that I wanted to work with, you know? People who cared about doing good things, about helping the poor people and helping the disadvantaged, and doing things like finding the racial injustice— all of the good stuff that I learned from my father, to tell you the truth.

So I was controversial from that point of view, but it was funny the way I lost accounts but not my reputation… I’ve got a reputation of being some kind of legend. They call me genius all the time. I did revolutionary, breakthrough advertising and editorial work. So I get unbelievable respect and good fame, and well-deserved fame by the good people of America. So I never really had a problem with how I feel about the war and how I feel about the government, etc. I guess somehow I’ve been lucky. Maybe it’s going to hit me sooner or later.

[Laughs] For me, it says more about integrity and principles than anything else and you made this visible through many of the Esquire covers. As for Esquire, there wasn’t a magazine like it before you got involved, and there hasn’t been anything like it since. Why do you think that’s the case?

Well, there were good magazine covers before. I think a lot of the good ones were—I’d swear they were—[American painter and illustrator] Norman Rockwell covers. But they were all about how wonderful American life is, and how homely and beautiful everything is. As he got older, he did some really good paintings, magazine covers of young black kids going to school with the cops watching them. But as far as just terrific covers, Norman did covers that America would watch—and get excited about.

And maybe there were some Life magazine covers along the way, due to their great photojournalism. But every once in a while they did a photograph that just got knocked back… When I did the covers for Harold [Hayes]… Actually, you know, before that, I hadn’t done a cover in my life. I don’t know if you ever read about how it happened…

Tell us…

Harold asked me to go out for lunch with him. I didn’t know what he wanted. Basically, he said he’d been reading about me— this “hotshot art director.” It was the first time an ad agency had an art director’s name on the door. At the time, we were the second creative agency in the world, after Doyle Dane Bernbach, so he was reading about Papert Koenig Lois—George Lois, and blah, blah, blah. Something made him call me up, because I was an art director and a designer. At lunch, he simply asked me if I could help him figure out how to do better covers. I said, “Well, how do you do them now?” He went through this litany of how he, and the other people in the art department, and the writers were all involved. He explained there were eight or nine or ten people involved in the decision every month, because they knew what was going to be in the issue. Between them, they decided what story should be made into a cover; what story deserved a cover.

He went on to explain that they all then went away to think about it and then came back in a couple of days with an idea or two. They’d pick three, or four, or five that they liked, and cut them. In the middle of it, I said, “Woah! Woah! Group fucking grope!”

He said, “What?” He was a Southerner, you know, and I was a little worried about it when I first met him because every Southerner I knew was a goddamn racist. But he turned out to be a trombone‑playing, ex‑Marine liberal.

And a maverick…

Which is an oxymoron.

[Laughs] Yeah.

[Laughs] In any case, he said, “What are you talking about?” I said, “Well, you can’t do great work with six or seven people working on something. Great work is done by one or two people, together.” He looked at me like I was crazy. Everybody in America—and everybody in the world—talks about “teamwork!” And I’m sitting there saying, “Teamwork? Bullshit!”

Everybody in America—and everybody in the world—talks about “teamwork!” And I’m sitting there saying, “Teamwork? Bullshit!”

“So, what are you talking about?” he asked. I said, “You obviously don’t have anybody there who knows how to do great covers because, otherwise, they’d come in with something and they’d show it to you and you’d fall down.” So I said, “Go outside [of the magazine] and get somebody.” He said, “I…you…I…you can’t… You mean, a designer?” I said, “Yeah.” He replied, “Well, how could they possibly understand my magazine?” I said, “What are you talking about? I’m an advertising guy. I read people. One day they come to me talking about their account. And if I get the account, within two or three days, I know more about their business than they do.” I told him I understand what they’re saying and I understand what they’re doing, and I understand how to make them famous.

I told him, any great advertising person or designer can look at the issue and figure out something that knocks you out and sells the magazine. And he said, “Well, who could do that?” So I started to give him names. Finally, after I gave him three or four names, he says, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa.” And with a Southern accent, “Hey, George, you’ve got to do me a favor, old pal.” I said, “Yeah?”… “You’ve got to do me just one goddamn cover because I don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.”

And that’s when I said, “OK. I’ll do you a cover. I owe you one cover. Tell me what’s in the issue.” He said, “Well, I got to go back and get…” I said, “No, no! Just tell me. Tell me right off the bat, right off your head, right now. Tell me what’s in the issue.” He said, “Yeah, but I need a cover in three or four days.” I said, “Yeah. OK. Just tell me. Tell me!”

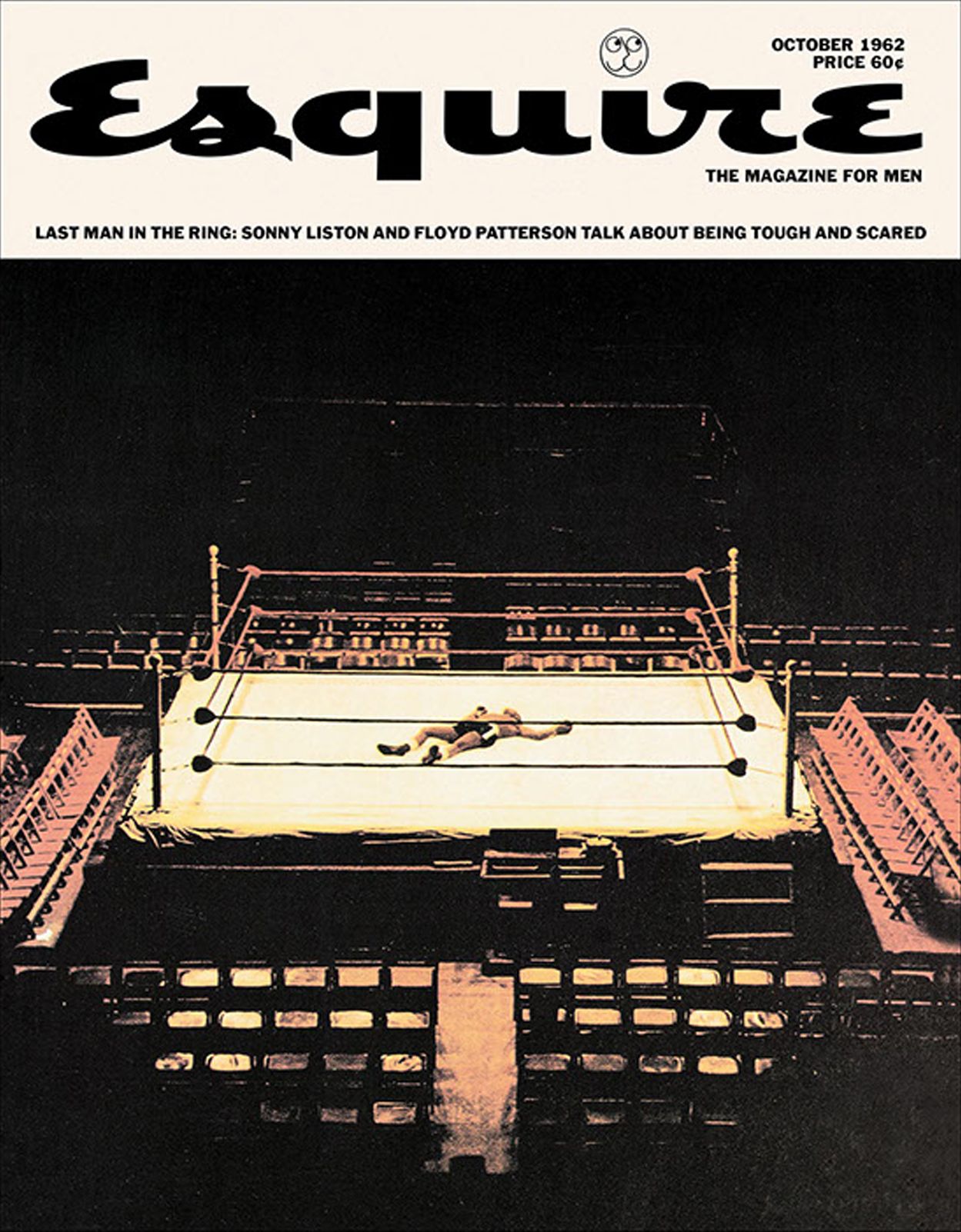

So he told me. I didn’t even take notes. One of the things he mentioned was that there was going to be a spread on Floyd Patterson, who was the world’s boxing champion at the time… He was fighting [Sonny] Liston, who was a nine to one underdog. I said, “OK. I’ll bring you a cover. I’ll send you a cover next week.” He said, “Next week. Really? What do you mean, a sketch?” I said, “No, a finished cover.” He thought I was crazy.

Anyway, when he told me he was doing something on Patterson and Liston, I immediately knew what the cover should be. Because I’m a fight fan, and I knew Floyd Patterson, and I watched him train. I knew that Liston would beat the living shit out of him. I just knew it. Even though Liston was the underdog.

I immediately called Harold Krieger, my photographer, “Get me a guy who’s built like Patterson.” We shot at St. Nicholas Arena, which is a fight arena up there. I think it was a Sunday. I got the pictures on a Monday morning, comped the cover and sent it over Monday afternoon, I think. Or maybe it was Tuesday morning, I forget.

About an hour later, Harold called and he said, “George.” I said, “Yeah?” He said, “I never saw a cover like this in my life.” I said, “No shit.”

And then he said, “But you’re calling the [result of the] fight.” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “But suppose you’re wrong.” I said, “Harold, I’m not wrong. I’m 100 percent sure. But look at it this way. You’ve got a 50/50 chance. If I’m right and the cover comes out—and I know I’m right—you’re Joe Genius, and everybody in America is going to say, “Whoa. Read Esquire magazine.” What a ballsy thing! And if it’s wrong—you’re fucked! You’re probably fucked, anyway.”

You know what he said to me? “You’re crazy.” And you know what I said back? “Harold, no, no, no. I’m not crazy. You’re crazy, because you’re going to run it.”

If I’m right and the cover comes out—and I know I’m right—you’re Joe Genius, and everybody in America is going to say, “Whoa. Read Esquire magazine.” What a ballsy thing! And if it’s wrong—you’re fucked! You’re probably fucked, anyway.”

[Laughs] And he did.

And he did. And now, let me tell you, I found this out many years later—six years later. Someone put together a book about all this, researched the memos and everything. When Harold showed my cover to the other people at Esquire, a couple people said, “Wow, it sure is different.” But almost all of them said, “But if he’s wrong about the fight, we’re dead.”

One of the Esquire founders, Arnold Gingrich, said no way, you can’t run this. Harold had just become the editor after a three‑way fight between him and two other editors. So he was pretty much on his own when he came to see me about covers. And, even though he had just gotten the job, he said to Gingrich, “If you don’t run this cover I’m quitting.” I didn’t know about this—and he didn’t tell me about it. Harold was a man’s man. He was the editor; he made the decision…

Anyway, Gingrich “let him do it” and when the issue came out—a week before the fight—it was bombed, because of all these sports records. All the sports writers—everybody—bombed it, saying how wrong it was, that it was ridiculous, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. In fact, in that issue there’s a publisher’s page by Gingrich, which says, “You see that cover? We didn’t do it. A designer by the name of George Lois did it. We think he’s wrong.”

You’re kidding!

I swear to God. Absolutely. I tell you, if you can find an original issue you would piss in your pants when you read it!

In any case, the night of the fight Liston just massacred Patterson in the first round. The next morning there were 100 articles all over TV, etc., etc. about how Esquire had called the fight. As for Esquire? I think they tripled their newsstand sales.

And I also found out, only four or five years ago, that Esquire were a couple of weeks, maybe a month, from going bankrupt. A few years ago Vanity Fair did a big story about me and the Esquire covers. They got together all the living guys, all of the editors, the writers, etc, for a photograph. I met many of them for the first time at that photo shoot because I never went to Esquire magazine. I always worked from my agency…

So you just did the covers and sent them over?

Yeah. I never went over there. I think a lot of people believe I was the art director of the magazine. I was never the art director. I just did their covers. And I did the covers my way.

But, when I met all these guys at the photo shoot, they were all telling me, one after the other—Peter Bogdanovich, Gay Talese and Nora Ephron—how they didn’t expect to get a paycheck that month. That’s how serious things were for Esquire. I didn’t know anything about it. Harold never told me any of this stuff. But almost immediately after I started doing the covers, their circulation went from 400,000 to almost two million.

You see, Harold understood it could take a long time, and a lot of hard work and risk, for people to understand how good a magazine is, and that the fastest way was to do something that knocked people on their ass. He had that kind of instinct, and it paid off for him.

I mean, to this day people say, “Gee, George you had some guts to do those covers.” But I say, I didn’t have any guts to do them. I did them because I wanted to do them. It was Harold Hayes who had guts… I mean, he had the biggest balls in the world. And I was saying this even before I knew all the back story about him threatening to quit if they didn’t run that first cover…

That’s part of the rarity I’m talking about with regards to magazines today.

Well, when you ask why can’t it happen today, it’s because there are no Harold Hayes. But I’m not saying there aren’t great editors. I think David Remnick of The New Yorker was a great editor, Graydon Carter [of Vanity Fair] is a great editor. But there ain’t nobody yet that’s had guts like Harold; it’s beyond guts. Anybody who wanted me to do covers would know right off the bat what the ground rules are, I would do the fucking covers my way. But nobody’s going to buy that today, not in this chicken-shit world. The only guy who brought it was Harold Hayes because he was just special; he was an incredible guy who understood, who had the instincts and the understanding… He understood: if you’re working with talent, you let the talent do it!

But there ain’t nobody yet that’s had guts like Harold; it’s beyond guts. Anybody who wanted me to do covers would know right off the bat what the ground rules are, I would do the fucking covers my way. But nobody’s going to buy that today, not in this chicken-shit world.

Remember my first lunch with Harold when I talked about the “fucking group grope?” I said to Harold, “Do you sit down with Gay Talese or Norman Mailer and have discussions—and a group grope—about how an article should be written?” He said he didn’t. “So then why the fuck would you do it on a magazine cover?” He looked at me like I was crazy, but when I proved to him that I could understand what the magazine was all about, he understood.

By the way, when I did those covers every month, I’d meet Harold first. We’d have lunch every month at the Four Seasons, which was a great restaurant. He gave me a rundown of what was good in the issue. He and I would decide what the cover would focus on, without any regard to what he thought was the most important article in the magazine.

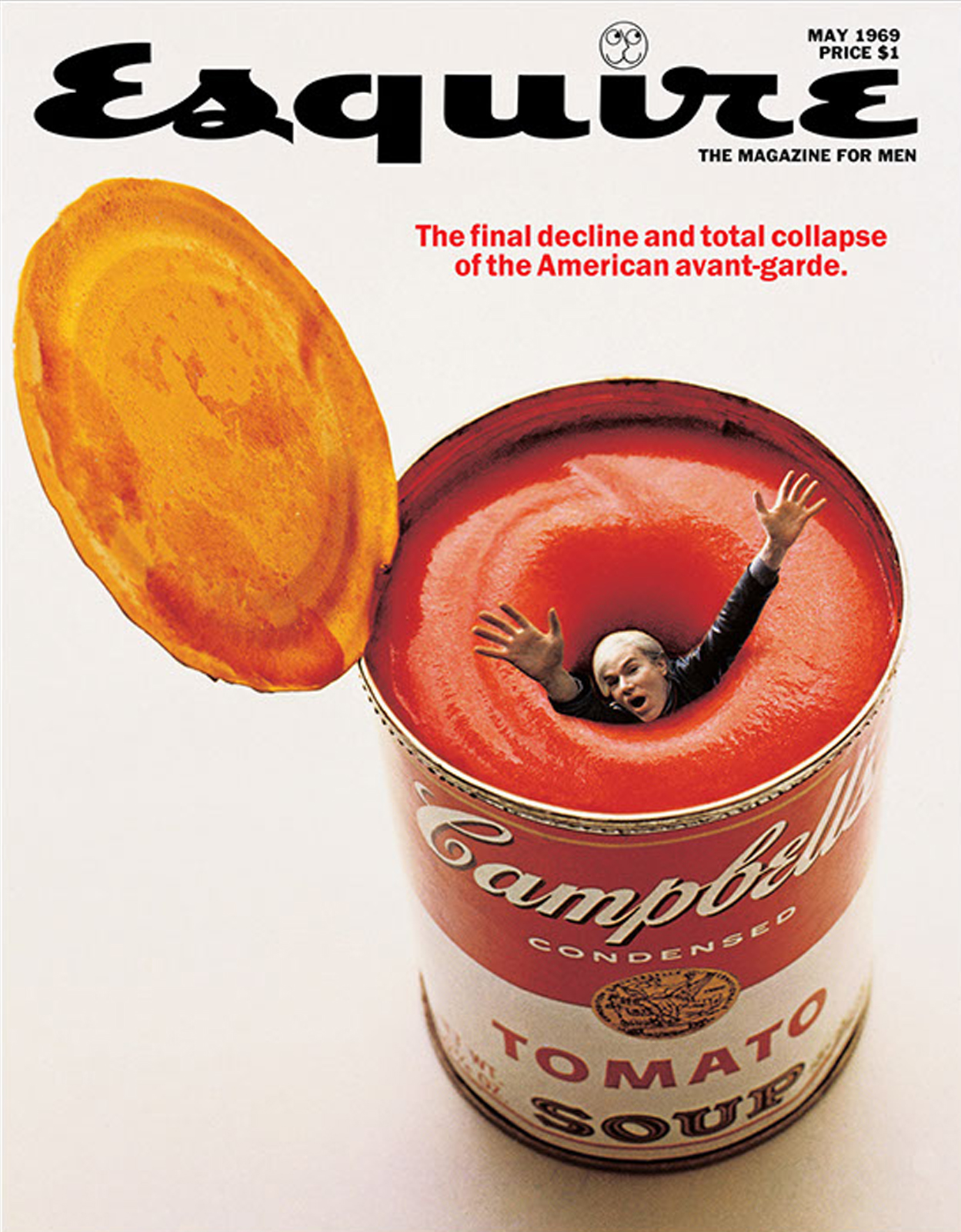

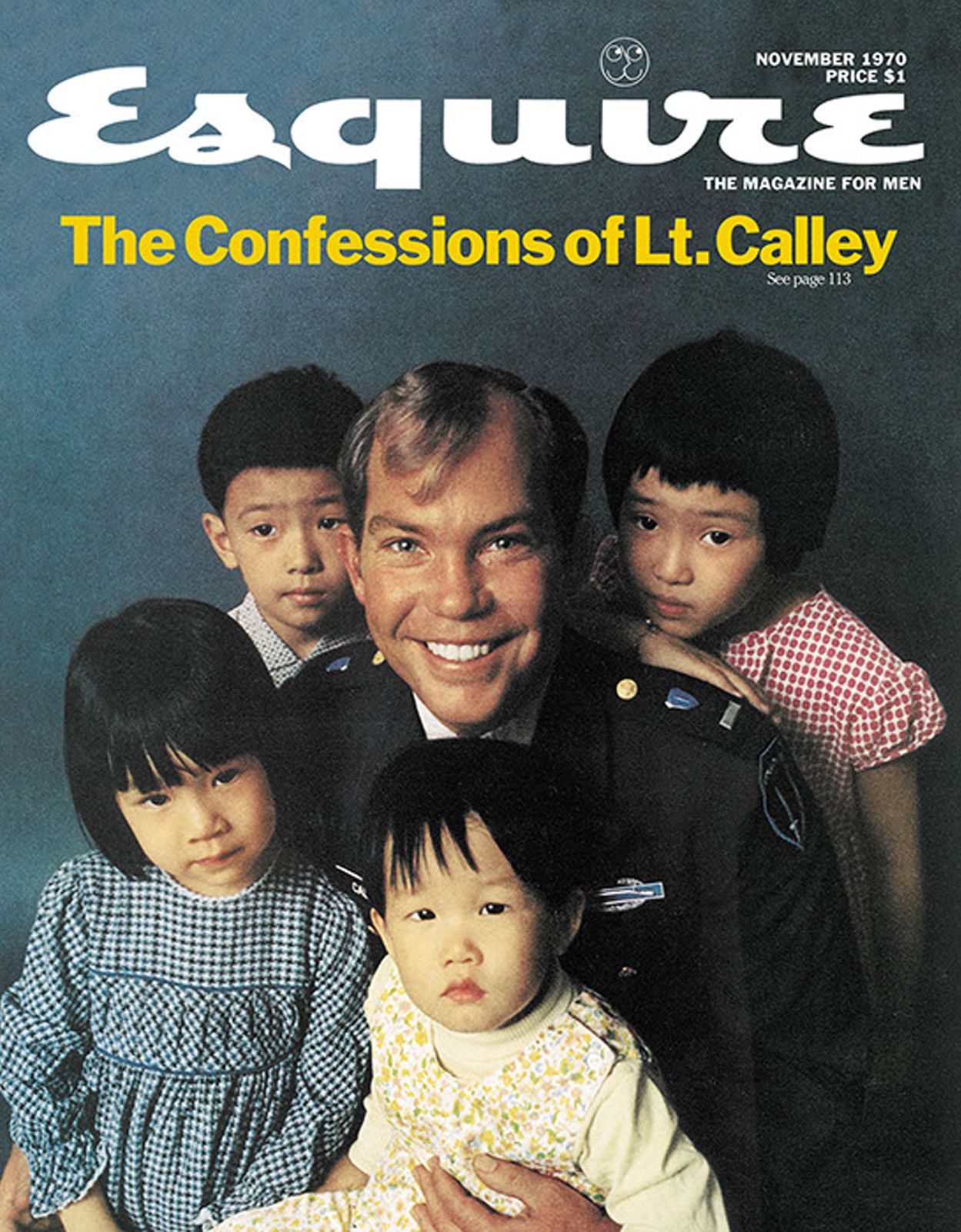

Once, there was a big story on what was going on with the avant-garde art movement and I’d said I had to do a cover about that. So I got Andy [Warhol] drowning in a can of tomato soup. Once there was a story about the lieutenant who was responsible for the My Lai Massacre—killing 500 civilians: kids and women—I knew I had to do a cover on that.

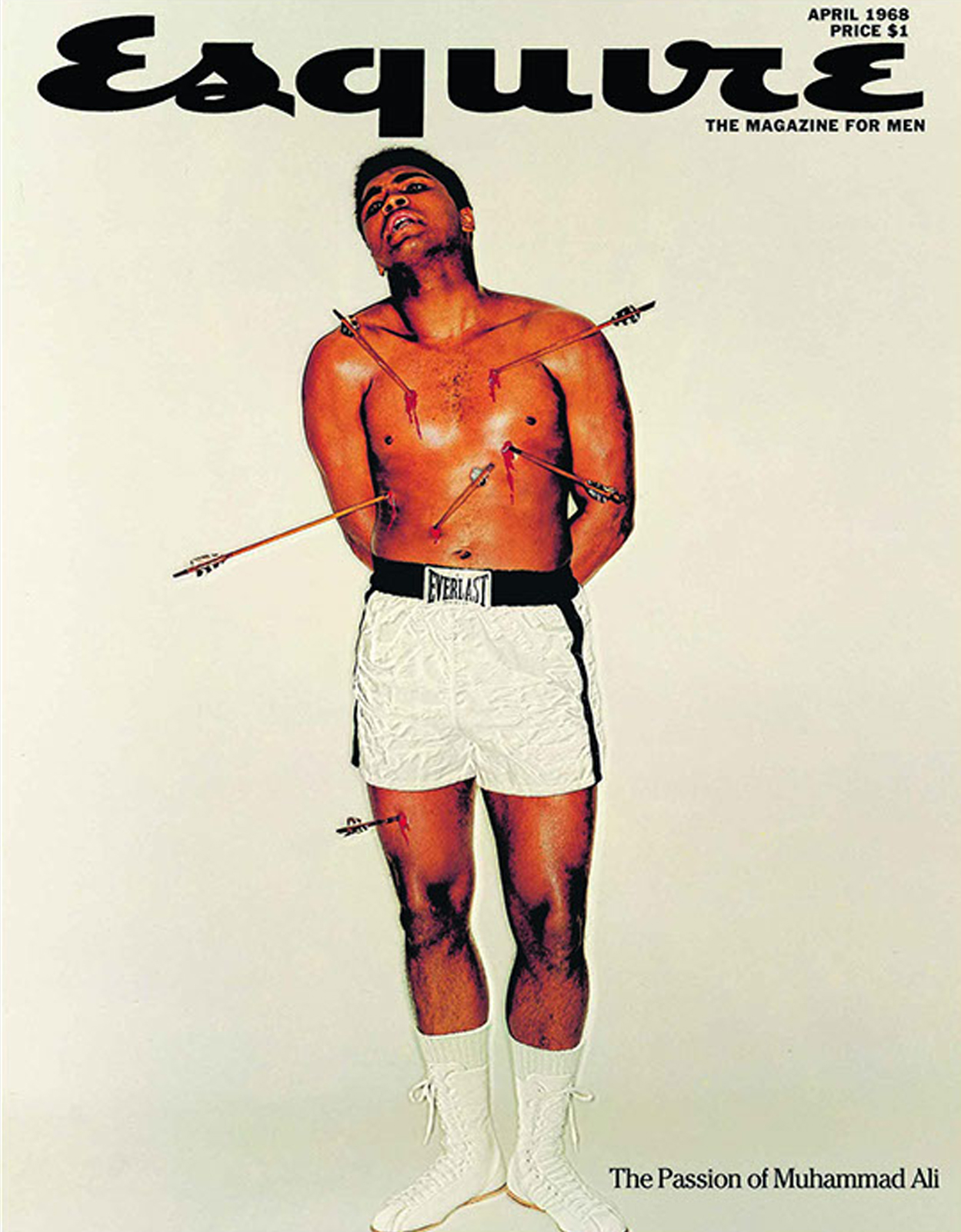

After I did three or four covers, we really trusted each other. I called him up and said, “Look, I want to do a cover, are you with me? I want Muhammad Ali, I think he’s a great man. You with me?” He said, “Yeah, I am. I think he’s a great man, too.” I said, “Everybody in America hates him. The blacks hate him because he changed his religion from Christianity. The whites hate him because he’s the big bad black kid… Everybody maybe hates him because he won’t fight for America. They say he’s a traitor. I think he’s great. I want to do a cover… I’m going to do a cover of him, showing him as St. Sebastian.”

I then said, “Now Harold, we’re going to get into big trouble when we run it. You might lose a lot of advertising.” “Yeah!” he said. [Laughter] Just that one word—“Yeah!” That’s how great he was. Because he understood when you do a really, truly great cover you can lose advertising. But he didn’t give a shit, because he knew he’d get the advertising back—two‑fold, or three‑fold—in a couple of months. He knew that a great cover would excite everybody in America. The really intelligent readers in America would just say, “What a great magazine.”

When I met you and heard you speak in Dublin, it was very clear to me that you’re a great persuader. You’ve been able to persuade Andy Warhol, Muhammad Ali, Richard Nixon, Mick Jagger, William Calley, and lots of people, to do things that you needed them to do…

Yeah. Well, there’s no doubt I am a persuader. The point is, I know how to “sell.” But it ain’t bullshit.

There’s no doubt I am a persuader. The point is, I know how to “sell.” But it ain’t bullshit.

Exactly.

I’m telling them what I really think. What I know in my guts, what I know in my heart. Anybody I talk to, they may not even really understand what I’m talking about but they look me in the eye as if to say, “This kid, this guy really knows. The guy really believes this.” As I got older, as I had more and more success, it got to the point where people would say, “Boy, this guy really believes in this thing—and look at his track record.”

So I got a lot of people to say “yes” who didn’t quite understand what I was doing, even though I explained the shit out of things. Campaign, after campaign, after campaign; I got away with doing it my way, and my way would make these guys multimillionaires… would make some of them billionaires.

And to this day I’m still working day and night. I’m working on some great projects. I get the big idea, I sell it, I show it, and I don’t think I’ve had an argument with a client in the last 10 years. They just look at me and say, “Yeah!” I say, “Yeah? Do you understand what I’m doing?” Sometimes I make them tell me what I’m doing. Sometimes—nine out of ten times—they explain it, and then some. So, for a creative person, the fight is to find great clients. And I’ve been lucky. Have you ever seen that documentary film, Art & Copy?

No, I haven’t seen it, yet.

It’s amazing. I was part of the film and I got people from all over the world calling me wanting me to do advertising, after they’ve seen it. I guess there were some moments in it where I was pretty passionate.

But a guy calls me up and says, “Just saw the film.” I said, “Yeah?” He said, “I’ve invented some eyeglasses for people who wear different close-up glasses and far-away glasses, like a lot of people over 40 years old do. I’ve invented prescription glasses with a lens that magnetically connects to a frame that I designed—a very special frame—with a little lever over the bridge of the nose. Using it you can focus on reading a newspaper, looking at a television set, or a movie, or a mountain range, all with the same pair of glasses.”

I said, “You’re kidding. That’s amazing. What’s the name of the glasses?” He said, “Trufocals.” I’m like, “What the fuck is Trufocals? What a terrible name.” He said, “What do you mean terrible? That’s the name. It’s on all the packaging now. It’s on all the glasses and we’re ready to advertise.”

I said, “Well that’s a terrible name.” I said, “I tell you what. I’ll do it if you let me rebrand it.” He thought I was crazy. “Rebrand it?” he said. “Yeah,” I said. “Look, this is exciting. Give me three or four days. Let me work on it.”

He’s based in California so I said, “If you’re coming in from California, I’ll show you what I’m talking about.” Anyway, he did. He talked to his marketing people and he said, “Let’s go talk to this crazy son-of-a-bitch.” He came in and I convinced him in about a second, because I showed him the name I came up with. I did a logo and a name called “Superfocus.” I also did a campaign with famous people putting on these glasses saying, “Now I see the world in Superfocus.” If you go to my website you can look them up…

But he instantly understood; threw out everything they’d done before and spent two months redoing everything—with a lot of money. At the beginning, we were going to run a three-month long campaign. But after two weeks, he calls me up and he says, “George, we’ve got to stop the advertising.” I said, “Why? What’s wrong?” He said, “George, we’re getting thousands of orders… We can’t keep up with making the glasses to fill the orders.”

I’m finding clients like that today… Clients who are entrepreneurs, who are all ‘big idea’… Really, I’m working on more exciting projects now than ever before.

In 2000, I retired. Ever since then my wife says, “George isn’t retired, he’s just tired.” I work night and day. I work with my son, just he and me, and no other people around. He’s a master on the computer—masterful. He was a photographer, and when I retired from my agency I said, “Luke, you’ve got to find me a young guy who is really terrific on the computer.” I worked with a lot of kids at the agency, and I could never work the goddamned computer. At the same time, I could never really teach them the power, I could never really make them understand, you know, what a great tool the computer is. They just didn’t get it; they didn’t get interested in what I was doing. They were just interested in the tool.

But Luke said, “Hey Pop, let me do it. I’ll do it.” I didn’t think he could, but the year I retired—or thereabouts—he went out and he bought all the equipment. I sat down one day and I said, “Holy shit, I hope the kid knows what he’s doing.”

I told him I wanted to do this, and this, and this, and this. So I’m sitting there writing, and he does it in front of my eyes. He and I have been working together ever since. We’ll work on four or five, maybe six projects at the same time—just me and him, alone.

That’s really nice.

I love it. I tell people: I used to go to the agency and, in the morning, when everyone came in, I’d have to say hello to 50, or 60, or 70 people. That takes a lot of time.

But now you’re freed up to actually work.

[Laughter] Yeah, now I go over to Luke’s studio and say, “How you doing, boy?” He says, “Hi, Pop.” We give each other a kiss. We sit down—bada boom, bada bing boom, boom, boom, boom…

[Laughter] Now… speaking of working, and speaking of advertising, you’ve been very vocal about the Mad Men TV series, which you say misrepresents the advertising industry by ignoring the dynamics of the creative revolution that changed the world of communications. You’ve said that mortal sin of omission makes Mad Men a lie. That’s pretty vitriolic. Is there anything in Mad Men that you think is even close to the truth of your first hand experience?

Well, I don’t know. I mean, I could be missing some of it because I never watched much of it. I’ve had people say, “Well, you know, I tell you George, there was something I saw there that was pretty good…” I say, “Maybe.”

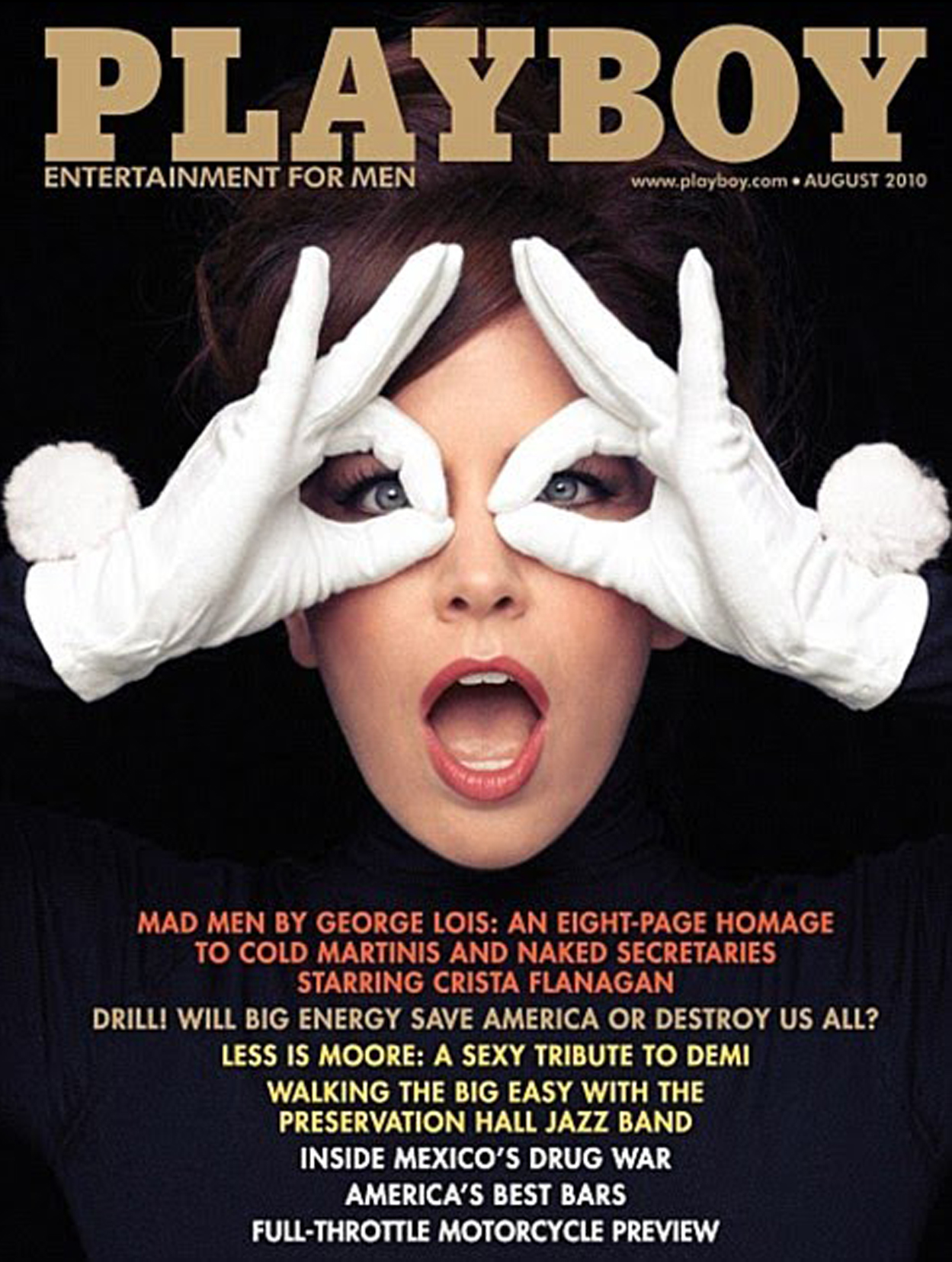

My basic argument, as I wrote in Playboy [see reprinted article at the end of this conversation] just before the series came out, everybody was hearing this buzz about this new TV show. It was everywhere, you know, and I was getting people calling me up saying, “Hey, George, they’re doing a show about you.” I must have gotten a hundred phone calls. And I’d say, “Huh? What are you talking about?” Then, I found out they’re doing a show about advertising in the ‘60s. So people said, “Well, if it’s not about you, then you must be doing the consulting.” Which I wasn’t. Then, finally, out of left field, I got this call from one of the producers saying he kept hearing my name from everybody that he called.

So I asked him, “You’re doing a show about advertising in the ‘60s and you’ve never heard of me?” He said, “Oh no, I’ve heard of you.” But I cut him off and said, “You’re full of shit…”

So I asked him, “You’re doing a show about advertising in the ‘60s and you’ve never heard of me?” He said, “Oh no, I’ve heard of you.” But I cut him off and said, “You’re full of shit…”

I understood right off the bat it was going to be a show about normal bullshit establishment agencies, where guys are shtupping their secretaries, and guzzling martinis and, you know, I said to him, “If you want to know what the hell was going on in the ‘60s get a book called ‘George Be Careful.’ It’s out of print, but I’m sure you can get it on Amazon. You’ll find out what happened in the ‘60s.”

Anyway, I figured that was the end of it, but I got a call maybe three or four days later. “Wow! Wow! We could have done a series just based on your book.” He started describing stories, things that are in the book and I thought “yeah, yeah, yeah—schmuck!” I told him he could’ve done something that made sense, something that was historically correct, something that really happened, about the ‘60s being a heroic age, instead of being a bunch of scumbags who only have one thing on their mind—screwing their secretaries, or whatever the hell else they did in the show. So maybe there’s something in the show, here or there, that’s got something right. But the whole basis of the show is so wrong, it’s infuriating.

I told him he could’ve done something that made sense, something that was historically correct, something that really happened, about the ‘60s being a heroic age, instead of being a bunch of scumbags who only have one thing on their mind—screwing their secretaries, or whatever the hell else they did in the show.

It’s interesting because…

It’s infuriating because, you know what? I get people saying to me all the time… “Hey, George Lois—(as well as other people, but)—he’s the original ‘Mad Man’…” And that’s infuriating because I’m not like any one of those sons-of-bitches! Know what I’m saying? But they still call me the original Mad Man, and they say it in a good way. I’ve read maybe 20 people who have written and said they based the TV show on me, and it’s a lie. It’s not based on me. It’s just that I was the hotshot in advertising in 1960, ‘61, ‘62, ’63… The fact people could characterize me as having that kind of ethos, you know? It’s not me, baby, no way!

On another note, your agency—Papert Koenig Lois—was the first ad agency to ‘flaunt the name of an art director on its masthead,’ which I believe ‘immediately raised the power, prestige and salary of graphic designers throughout the industry.’ Why do you think the value of a graphic designer increased exponentially, simply by changing their title to an art director in an ad agency?

Well, you’ve got to first understand the history, which of course begins with Bill Bernbach, who started Doyle Dane Bernbach in the ‘50s. It’s also based on the fact that Bill was lucky enough to have had the chance to work with Paul Rand.

When Paul did advertising he worked by himself: he wrote everything, he did everything himself. Someone at DDB suggested to Bill that he should work with Paul. Paul was a tough guy. They said, “He may not want to work with you; he may throw you out of the room. But maybe you can get along with him.” When he went to see him, Paul almost told him to go fuck himself.

Now I had many talks with Paul Rand and Bill Bernbach, separately, so I got the story. Paul was very suspicious of Bill, but after a while, we’d be working on stuff and, before anyone wanted him to work on it, Paul would say, “Hey, I got a headline.” He had it all figured out. But Bill would say something like, “Gee, Paul, I like what you’re doing. Maybe instead of saying “blah, blah, blah” you should say it this way and … Here’s a little piece of copy maybe you could use.” And Rand started saying, “Hey, he’s really helping me. That’s good, you know?”

You’ve got to first understand the history, which of course begins with Bill Bernbach, who started Doyle Dane Bernbach in the ‘50s. It’s also based on the fact that Bill was lucky enough to have had the chance to work with Paul Rand.

Of course, what Rand understood was, when you work with a graphic communicator the advertising can be better—Duh! No shit. But it was an epiphany to Bill Bernbach. An epiphany! Because before that he, like the rest of the world, would write copy like a copywriter and go to the art director’s room and the art director was sitting in a room with his thumb up his ass waiting for a piece of copy so he could do a layout.

So Bill’s epiphany in the ‘50s was that he began to understand great advertising is not a copywriter working by himself—almost never, actually—but that a copywriter working with a gifted art director could make magic.

All that time Bill had his agency—and he did what he did—but he revered the art director. I mean, writers in DDB did OK, because he was a writer and he could do that. But he treated Bob Gage, and me, and Helmut Krone, and Bill Talman, like we were gods. In any case, when he started his agency he went to Paul Rand. It’s a little known fact, by the way. He said, “Paul, I have two accounts and I’m starting an ad business and I want you to come in with me.” And Rand said, “Go fuck yourself.” But then he said, “There’s a kid—wait, wait, wait a minute, don’t go. There’s a kid in the promotion department, by the name of Bob Gage. I think he’s got a lot of talent.”

Bill Bernbach got that guy, Bob Gage, to be his first art director and Bob Gage made Doyle Dane Bernbach the success it is today, the success it became, because Bill immediately had this one terrific designer and thinker, a guy who could write, a guy who understands—a guy who understood humanity…

There was a great graphic bunch. He hired his first writer, Phyllis Robinson (who died in 2010). Together they did the advertising that made everybody in America who had brains say, “Wow, what the hell is going on?” They had something terrific going on. So Bill understood the power of the art director, and he revered it.

I always said—in fact, I once told Bill when I was 26 and he laughed his ass off—I said, “Bill, I, um, I do great advertising when I work with a great writer.” He looked at me and said, “Yeah?” “Bill, I do great advertising when I work with a mediocre writer, with a fair writer.” He said, “Yeah?” “Bill, I do great advertising when I work with a lousy writer…” He said “Yeah?” And I said, “Bill, I also do great advertising when I work with no writer.” And he looked me in the eye, shook his head and said, “You’re right,” because the first day I got to the [DDB] agency, when he and Bob Gage hired me, Bill came into the office at nine in the morning or 9:30am to welcome me. But I had been there from 5:30 in the morning, which I always did.

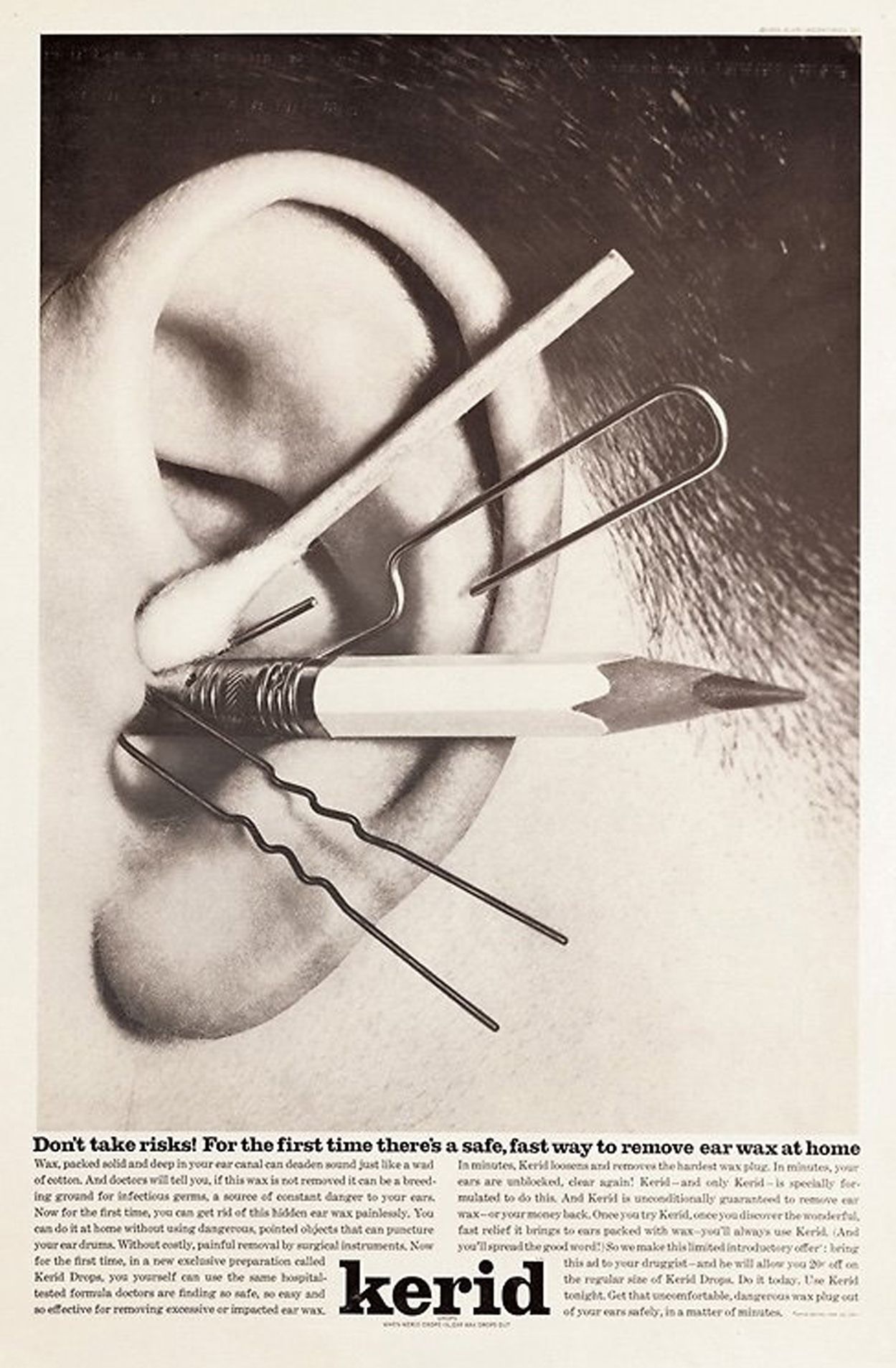

Strewn over the floor were about ten layouts of tissue paper, stapled to bond paper. Bill came in and he looked at my room. He said, “George, welcome. But what are these, what are these layouts?” I said I was working on ads. When I got to the agency at 5:30 in the morning there was a requisition on my drawing board for a product called Kerid, which was an earwax removal. It was a liquid that you put in ears. So I told him about the product and he said, “George, I understand the product. I’ve got the account, you know!” (Like he was saying, “you schmuck!”) I said, “Yeah, well, anyway. I’m working on some ads.” And he started to glance at them.

They were on the floor. They were, you know, simple, beautiful drawings with headlines and body copy written out. He said, “George, these are remarkable. Who’s your writer?” I said, “Bill, I just came to work at 5:30 this morning. The brief was on my drawing board. I’m just working on them.” He said, “Yeah, but who’s your writer?” And I said, “Bill, I don’t need a goddamn writer.” He looked at me and said, “I’ll be your writer from now on. I’ll do all your writing.”

He understood that a great art director runs the show. I don’t care who your writer is. You know, you can work with a writer… Can I say something here?

Go for it.

They don’t put it down. I put it down! You know what I mean? I do whatever the hell I please. And if you work with a great writer, well, terrific. But one of my problems is, when you work with a great writer it’s very difficult because one out of ten times great writers come up with a line that you can do something with mnemonically, visually. When I create, I do lines all the time in my head and I can see them visually. I turn down 20 lines that I think are terrific until I get one that works, you know like, “I Want My MTV.” Then, visually, I’ve got Mick Jagger picking up the phone. Visually you see him picking up the phone and you remember the line “I Want My MTV.” How can you forget it?

When we started Papert Koenig Lois, besides the fact Koenig and I had left Doyle Dane Bernbach where we had the greatest jobs in the world, the big news was there was an art director’s name in a major agency. Even though the art director was, kind of, king at Doyle Bane Bernbach, what happened with Papert Koenig Lois really dotted the “i”. Three or four months after we set up Papert Koenig Lois, Bernbach smelled it; he smelled what was going on and gave his five top art directors $20,000 raises. That was a lot of money back then.

He figured it out, and he told me about it a year later. I said, “Bill, when you gave everybody their $20G raise, it was a big thing and everybody in town knew it. What made you do that?” He said, “You did!” He never cursed, he was a real gentleman, but it was almost like saying, “Fuck you, you did it.”

But he really understood, you know. By popping “Lois” in the company name this changed the dynamics of, well, certainly the payroll. This was in 1960—’61. By 1963 or ’64, top art directors in the so-called creative agencies were making, like, $200G’s. You know how much money that was back then? They knew the name of the game was the art director.

Again, I’m not negating the writer but the point is—and it sounds terrible for me to say this—but you can always find a writer. But if you’ve got the right art director you don’t need a writer. I mean Bob Gage didn’t need a writer. He was a terrific, very sweet man and he worked well with Phyllis Robinson and everybody else there. But if he was alone, trust me, he would’ve done great advertising, following in the footsteps of Paul Rand.

As for Paul, he said, “I don’t need no copywriter, those motherfuckers.” [Laughs]. Paul was a wonderful guy. He was the most cantankerous man that ever lived. One of the great stories about Paul Rand was, whenever he got an award he’d say, “Get Lois to give the talk about me— to present the award to me.” The awards people would call me up and say, “Paul Rand wants you to do the talk on him about getting this award in New York.” This was the Type Directors Club calling me! I said sure, I’d be glad to do it, right? I mean I had done about four before.

So, I gave a talk to more than 800 people—type directors, every type director in New York. I gave this talk and Bill [Bernbach] was on the dais with me. Anyway, I love to talk about Paul. I gave this wonderful, edgy talk about him and then 800 men—every one of them was a man, there were no women type directors back then—they were cheering and cheering and cheering and cheering.

Bill stood up and then he stood next to me and they were still cheering and cheering. They didn’t stop. They’d gone on for minutes. I looked over at Paul, like maybe there’s a tear in his eye or maybe he’s choked up a little bit, you know? And he kind of leaned over to say something to me and I figured, “Oh, he’s going to say something sweet.”

He said, “George, everybody in this room is an asshole except you and me.”

[Laughter] Isn’t that great? When I tell that story to guys just like Paul, like Lou Dorfsman when he was alive, and Herb Lubalin when he was alive, the guys I really respect. I’d tell them that story, and they’d laugh their ass off. They used to say, “That’s Paul. That’s why he was so loveable.”

Imagine it, “George, everybody in this room is an asshole except you and me!” And those people are cheering and cheering. [Laughs]

[Laughing] Part of your power and charm is your ability to captivate people with stories…

People say I’ve got a million stories and I say, “Well, I’ve got a story for at least every week of my life.” Working in advertising and working in what I do, I’ve got to. There’s got to be stories; you can go into work on Friday and say, “Gee, what’s the best story this week?” I can think of loads of things that happened.

I tell designers that if they’re not brave—if you’re not literally, physically and mentally brave, you can’t be a great art director. And in order to be physically and mentally brave, and to be able to sell your work, you’ve got to be able to know how to talk passionately about it.

But I was lucky. When I started out I had a lot of other great stories—before I started my own ad agency. But once I started my own ad agency I had a lot more stories because you’re involved in so many more things, you know? I tell designers that if they’re not brave—if you’re not literally, physically and mentally brave, you can’t be a great art director. And in order to be physically and mentally brave, and to be able to sell your work, you’ve got to be able to know how to talk passionately about it.

So when I tell stories, I think they add up to something because I’m not telling them out of left field, you know what I mean? It leads to a lesson.

I guess it’s really a result of living life, and being able to tell those stories in a compelling, interesting and unique way…

Yeah, well, you know, I’ve been married to the same woman for 60 years and loved every day of it. And we went through some hard knocks. Lost my 20 year-old son the week after his birthday. I still cry every night over it, you know? Life ain’t easy. But life is a joy, and you should live your life joyously and passionately. And you should want to get things done every day of your life!

Editor’s Note: Below is the Playboy article mentioned in the interview above.

IT’S A MAD WORLD

With a dissenting view from George Lois, the original Mad Man.

‘It’s a Mad World’ originally appeared in Playboy Magazine (August 2010 issue) © 2010 Playboy. Following is a transcript of the original manuscript, kindly provided by George Lois and reprinted with the generous permission from Playboy Magazine.

The buzz in town was that a great TV series was about to premiere dealing with the ad game in the 1960s. To me—and those savvy about watershed advertising and media events in American culture—that meant only one thing: a popular television show dealing with the explosive triggering of the legendary Creative Revolution was about to be born. In the ’60s, the dynamic impact of ethnic, passionate, and supremely talented graphic designers and copywriters had turned the ad world upside down, commanding the attention of America and the world with bright, witty, entertaining advertising. The Creative Revolution exposed the traditional advertising world for what it was: Wasp-driven, hackneyed, untalented–simply put, hacks. The news of the Mad Men series was exhilarating to all of us who played prominent roles in that watershed event, but, I wondered, how could they do the period justice without contacting me, the original Mad Man, for input, to consult, or whatever.

The Creative Revolution exposed the traditional advertising world for what it was: Wasp-driven, hackneyed, untalented–simply put, hacks.

And then, out of the blue, a Mad Men producer called me and told me they were tracking down some “real Mad Men” (and a few Mad Women), to film some promos for the show, and every old-timer they contacted blurted out something like “You gotta get George Lois–he was the catalyst who dominated the ’60s.”

“Whoa,” I said to the clueless Mad Men caller. “You mean that you guys are doing a TV series based on advertising in the ’60s and you never heard of me?”

“No, no,” he protested, “we know who you are.”

“Bullshit,” I said, and told him that if he really wanted to know what happened in the ’60s, he should read my biographical book George, be Careful: a Greek florist’s son in the roughhouse world of advertising. “It’s a blow-by-blow account on how I triggered the Creative-fucking-Revolution that changed the ad world,” and hung up, plenty miffed.

The stunned producer called back a week later and with bated breath said “Wow! We could have done a TV show just based on your book! That scene when you hung out a window and threatened to jump if the client didn’t buy your Matzos poster was hilarious!” I told him to kiss my ethnic Greek ass and hung up.

Gradually, but surely, after the revolutionary Bauhaus design movement and during the post World War II period, a counterculture began with the advent of young, basically Jewish, American modernist designers, culminating in the early 1950s when copywriter Bill Bernbach started working with the pioneering Paul Rand, the guiding mentor of the New York School of Design. It was the first time two creative geniuses—one a copy writer, the other an art director—had teamed to create ads together. The experience inspired Bernbach to found the now-legendary agency Doyle Dane Bernbach, joining talented copywriters with visionary graphic designers, and the first truly creative agency was born. Power had been taken away from the account executives and businessmen and transferred to the talented people who actually made the ads. It was an inspiring time to be an art director like me with a rage to communicate, to blaze trails, to create icon rather than con. The times they were a-changin’.

Suddenly, in the very first week of the 1960s, as the wunderkind of the New York School of Design and after a thrillingly successful year as an award-winning art director at DDB, I left Bernbach’s atelier, and with two copywriters as partners, started what seemed unthinkable at the time–the world’s second creative agency. Papert Koenig Lois inspired and triggered what is revered today as the Advertising Creative Revolution—when a handful of other creative groups, buoyed by the instant success of our trailblazing firm, also formed agencies based on the art director/copywriter team concept. Madison Avenue would never be the same. (PKL was the first ad agency that flaunted the name of an art director on its masthead, immediately raising the power, prestige and salary of graphic designers throughout the industry.)

That revolutionary counterculture found expression on Madison Avenue through a new creative generation—a rebellious coterie of art directors and copywriters who understood that visual and verbal expression were indivisible, who bridled under the old rules that consigned them to secondary roles in the ad-making process, which was previously dominated by non-creative hacks and technocrats, and who became the heroic movers and shakers of the Creative Revolution. Those men and women, mostly the offspring of immigrants, bear no resemblance to the cast of characters in Mad Men.

Up to that time, the traditional advertising agency (depicted in Mad Men as the fictitious Sterling Cooper agency) was comprised of fools and frauds who ran ideas up a flagpole to see if someone saluted; when clients were arrogantly conservative; when the art director had no part in the creative process as he sat with his thumb up his ass waiting for the talentless copywriter/account executive team to deliver copy for him to form into a traditional uninspired layout; when committee group-grope reigned and lawyers restrained—all resulting in insipid, brutally dull and/or obnoxious TV and print campaigns that contaminated the American scene.

In creating a popular TV show based on an ad agency, the producers went whole-hog to depict the scum of the industry, rather than the upbeat world of culture-busting creativity. Mad Men has given the world the perception that the scatology of the Sterling Cooper workplace was industry-wide.

That mind-numbing mediocrity was more typical of the ’50s than the ’60s (and they still exist today). Mad Men misrepresents the advertising industry by ignoring the dynamics of the Creative Revolution that changed the world of communications forever. That mortal sin of omission makes Mad Men a lie. Matthew Weiner, the creator and show-runner of Mad Men, rejects my feelings about his show by stating that “George Lois is a legend… but Sterling Cooper is not cutting-edge; it’s mired in the past,” calling his characters “dinosaurs.” Huh? In creating a popular TV show based on an ad agency, the producers went whole-hog to depict the scum of the industry, rather than the upbeat world of culture-busting creativity. Mad Men has given the world the perception that the scatology of the Sterling Cooper workplace was industry-wide. In their advertising, they have the balls to proclaim that “Mad Men explores the Golden Age of Advertising,” but they surely know they’re shovelling shit. Their show is nothing more than a soap opera placed in a setting of a glamorous office where stylish fools hump their appreciative, coiffured secretaries, suck up martinis, and smoke themselves to death as they produce dumb, lifeless advertising—oblivious to the inspiring Civil Rights movement, the burgeoning Women’s Lib movement, the evil Vietnam War, and other seismic changes during the turbulent, roller-coaster 1960’s that altered America forever. (In the after-hours, when the Stering Cooper stiffs were screwing their staff, we athletes at PKL were playing ball on the best amateur softball and basketball teams in New York City. To each his own.)

The more I think and write about Mad Men, the more I take the show as a personal insult. So, fuck you Mad Men–you phoney “Grey Flannel Suit,” male-chauvinist, no-talent, WASP, white-shirted, racist, anti-semitic, Republican, SOBs!

Besides, when I was in my 30s I was better-looking than Jon Hamm.

Image Credits:

George Lois portrait by Telegraph Weekend Magazine sourced on Chris Buck News

Mad Men promotional photograph sourced on Across the Margin

Esquire covers sourced on George Lois’s website