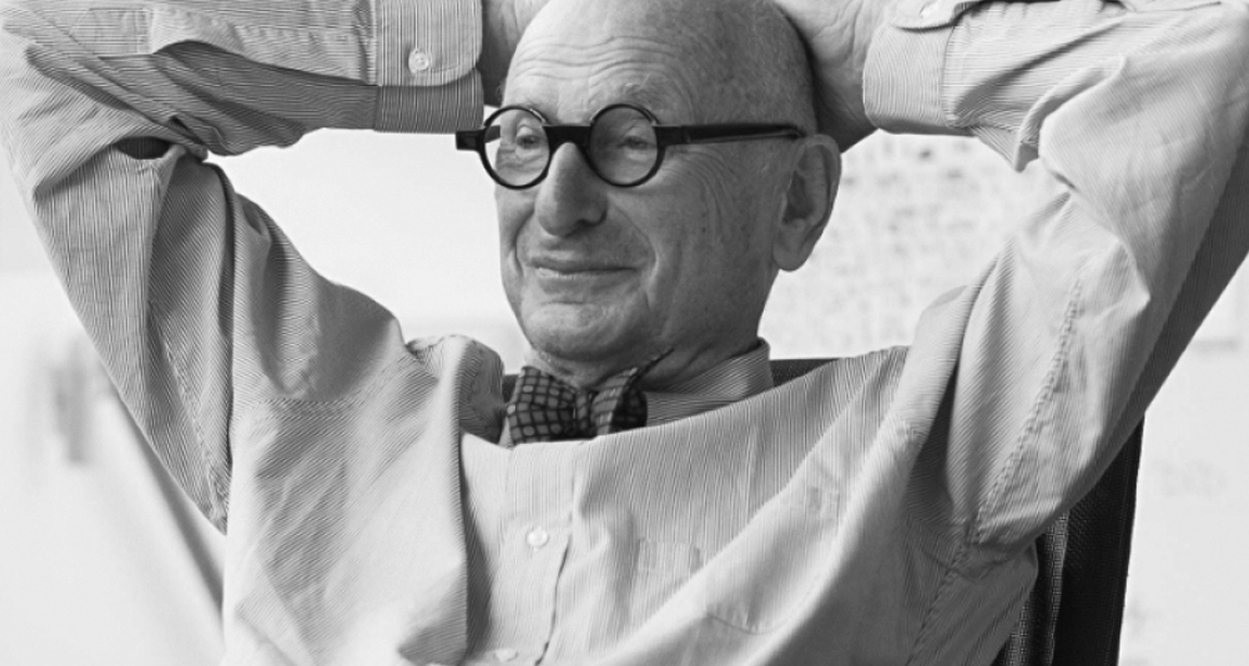

Wally Olins—hugely influential co-founder of the seminal branding firm Wolff Olins and then Saffron Brand Consultants—provides a masterclass on all things identity and branding. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #5 which focused on the theme ‘Identity’. (Sadly, Wally passed away in 2014, aged 83.)

Note: This interview took place in 2008 and refers to specifics from that time.

Kevin Finn: Briefly, what is the difference, if any, between a corporate identity and a brand identity?

Wally Olins: Well at one level, brand identity and corporate identity and reputation—all of these words—stand for the same kinds of things. But there is no doubt though that the semantic difference between brand identity and corporate identity is profound. ‘Corporate identity’ is an academic, almost loose woolly term, whereas a ‘Brand’ is about money. So when you start talking about a brand you start talking about a subject that is very close to a corporation’s real interests.

There is no doubt though that the semantic difference between brand identity and corporate identity is profound. ‘Corporate identity’ is an academic, almost loose woolly term, whereas a ‘Brand’ is about money.

Do you mean Corporate Identity is something more cosmetic?

Some people might think so. If you like, it’s a derivation of another phrase ‘house style’ which is no longer used and which implies an external presentation of the organisation. Corporate identity doesn’t necessarily imply external. ‘Brand’ certainly doesn’t imply external, although some people think it does.

But when you talk to a commercial organization about brand strategy they know that it is about money and is therefore worth talking about. The long-term implication is that it puts brand strategists and brand consultants right at the heart of the business world. Corporate identity does not do this. This also has knock on implications we can talk about later if you want, in relation to advertising agencies and so on.

Before we get into that I’d like to talk about a wider issue, about your views on how branding, and its associated activities, has broadly shaped our society today.

Well, again, branding is at the heart of today’s society simply because branding is about manifestations of identity. It’s a demonstration of who and what you belong to, and in a world that is increasingly competitive this is important, not just in commercial life but in every kind of activity you can think of including sport, the Nation, the city, the family. Inevitably then, what brand you choose to belong to, what brand you choose to associate yourself with is of profound significance.

My view is that corporations are increasingly going to be seen as being socially responsible because, if you like, ‘conspicuous consumption’ is to a certain extent giving way to what you may call ‘conspicuous compassion’. That means people who buy things want to be seen to be giving as well as buying. And corporations with which they deal will have to demonstrate an association with some kind of socially responsible activity. And that in turn means a knock on effect for not-for-profits and charities.

Corporations are increasingly going to be seen as being socially responsible because, if you like, ‘conspicuous consumption’ is to a certain extent giving way to what you may call ‘conspicuous compassion’. That means people who buy things want to be seen to be giving as well as buying.

When you start looking at that area you can see that the brand becomes particularly significant because the only thoughts that a charity or a not-for-profit can engender in people’s minds, are emotional. You don’t get anything out of going to a charity except emotional satisfaction. And that brings you back to branding again.

With branding being such an integral part of today’s society we’re somewhat over-saturated every day by this branding and general visual stimulus. To some extent, do you think the general public tends to switch off or become numb to all this? Or is it more a case of branding having heralded a kind of visual literacy amongst the general public?

I think, if you’re talking about luxury brands, or consumer brands—the things people buy—there is such a plethora that certainly some people are becoming numb. I think that’s true.

On the other hand, one should never underestimate the ingenuity of commercial organisations to seduce people. And if a commercial organization believes that it will be in its interests to become charitable, or to be seen to become charitable—I don’t want to sound cynical here but the appropriate phrase is ‘enlightened self-interest’—if they see it as being in their interest to be socially responsible, then that is what they will do. And that is a very powerful mechanism for change.

There is another mechanism at work, which is also significant; branding has entered sport, and the arts, and music, and culture in a huge way, both for better and worse. For better: because it makes them more professional, more effective and more available. For worse: because it inevitably has the effect of commercialising them.

In your recent book ‘Wally Olins: The Brand Handbook’ you state there are some who claim: Brands represent the consumerist society at its sickest. How do you respond to critics of branding, for example the Naomi Kliens’ of the world?

Well Naomi Klien has written a very interesting book [No Logo] but it is based on an entirely false premise. The idea she works with is that the brand itself has a morality. In reality the brand has no morality. It simply presents whatever it is representing in the most powerful and visual and emotional form.

Someone, I’m afraid I can’t remember who, recently wrote a book that was violently anti-brand on the basis that ‘brand’ had spawned the fascist Nazi and Communist governments in the 1930s and people have written serous reviews about how appallingly subversive brands are, and so on and so forth. What these people fail-—or choose not to—understand, is that the brand is without morality.

I’ll use an example: the Red Cross or Amnesty International. Do they make the brand good? The ‘brand’ is used, as a tool, by people who want to communicate a series of ideas and if they happen to be good ideas, or beneficial ideas or charitable ideas then the brand is ‘good’. If they are commercially seductive, then some people might regard them as ‘bad’. If they are politically motivated, depending on your own political motivations, people will look at them accordingly. The brand doesn’t have a morality. It is something we use. We need to belong. The brand is a demonstration of belonging. So [No Logo] is wrong. It is based on an entirely false premise.

The brand doesn’t have a morality. It is something we use. We need to belong. The brand is a demonstration of belonging.

Brands aren’t good or bad. You could say capitalism is good or bad. What [Naomi Klein] is saying is that capitalist society at its sickest uses brands to seduce and manipulate people. Well it does, if you choose to be seduced and manipulated then you will be. But if you don’t choose to be seduced and manipulated you don’t have to be.

Where in all this does the responsibility of the graphic designer fall? Do they even have jurisdiction? For example, Peter Saville says about branding: The job is to steer and engineer people’s perceptions of things towards a profitable outcome for your clients—that’s the job… It’s a misleading conspiracy, you know. It’s smoke and mirrors. The brief is: make us look like we believe in something, make us or our product look believable, [and] look like we mean something. That’s the job. Isn’t this a sound argument?

Well, I think that is a rather extreme way of putting it but fundamentally, I don’t disagree. Where I think he and I might disagree is in the assumption that one can create a smoke and mirrors idea with which one can consistently fool people. But this is not likely to work for very long because when people find out that what you sold them is rubbish they won’t buy it again. It is a mistaken assumption, as Naomi Klein believes, and Peter may suggest he believes (though, I’m not saying he does believe) that you can fool all the people all the time. You can’t. If you are seduced into buying something and you don’t like it, well you won’t buy it again.

Of course, that is the power of a brand—it makes a company/product very visible.

It makes it very visible and very seductive the first time. And if you don’t like it you won’t have it again. And that’s the point. You know, this is not Nazi Europe. You have a choice. You can turn off. And I can give you a number of examples of this.

MG was a much loved car brand because for over forty or fifty years it built up a reputation for being the first fun car that lots of kids had. It looked lovely and won races, and all that kind of stuff. Over the following thirty years the company which owned MG systematically destroyed it, apparently almost on purpose. They destroyed everything about it: they produced lousy cars, they put the badge on cars that were entirely inappropriate, and so on. In the end, even the greatest admirers and lovers of MG weren’t convinced. They’d buy the old MG cars and not the new ones.

That is a company which destroyed itself because it was cynical and misused its heritage. But people didn’t fall for it. One can think of other examples of products or organizations that destroyed themselves in this way. All the time there are organisations that stop existing because they’re no good any more.

Another example: Andersen Accounting. One of the ‘great five’, the biggest of them all, destroyed itself overnight. It happens again, and again and again. It is absolutely not the case that people are victimized, seduced and manipulated by brands to the extent that they go goggle-eyed and buy them despite anything else—they don’t.

So while I don’t disagree with what Peter Saville says, what I don’t think he takes into account sufficiently is choice. There are hotel chains I don’t go to no matter what the advertising says, no matter what the communication says, because I don’t like the experience.

The issue is, if you’re buying products that are so similar in rational terms, like price, or quality or service, then it is almost impossible to choose rationally. Then you have to choose by emotion.

If you’re buying products that are so similar in rational terms, like price, or quality or service, then it is almost impossible to choose rationally. Then you have to choose by emotion.

Another interesting thing Peter Saville said was, and it perhaps has to do with the visibility of a brand and the social responsibility of a brand: “a key thing for a brand is that it must be a regular and frequent ‘news generator’. If it is not generating news it is clipped out of our awareness. And the news it generates must be on message.” Would you agree that, in today’s world, it is the news cycle which dictates how people see a brand in a more detailed way?

Yes and no, because that does not take into account web content. That was true until a very few years ago, simply because all content about anything was generated by the conventional media. Now it can be generated, and is generated, by everybody. So, if I want to make a noise about this watch [pointing to his wrist watch] and there hasn’t been much in the newspapers, or on the radio, or the television recently, I’ll make a noise about it in a blog. And I’ll put it on YouTube, or My Face, or Your Face or Upside down Face, and I’ll make a noise about it, either because it’s lovely, or it’s not lovely, or because I feel like it.

Georg Jensen is the name of this watch brand. Georg Jensen was an incestuous rapist and so on. Obviously, I just made that up. But if I put it on the web somebody would pick it up and there would be a whole performance about it. [Both laughing.]

It’s interesting that you mention Facebook and the web. How has technology changed things in branding?

Well, for people of my generation, not at all. I mean we kind of know about [new technology] and we use it in a hopeless, pathetic sort of way. I am very uncomfortable with it. But I recognise that it has immense power and the power that is has hasn’t even affected your generation [pointing at Kevin Finn], you’re too old for it. The power has affected twenty year olds, twelve year olds.

I was asked yesterday about the Wolff Olins 2012 Olympic logo, which I had absolutely nothing to do with because I wasn’t involved in the company then. And as I mentioned yesterday, the first time I even knew about it was when a journalist phoned me. But I could immediately see the Olympic 2012 logo was not a piece of standard print design.

So what’s it about?. It’s designed for the web. So I looked at it online and it’s marvellous. It changes colour, it jumps around, it works with other logos. So how will [technology] change for generations below you? It will change life hugely. How? A) They will be able to answer back, and they already do. B) Everything will move, and dance and jump around the place. It’ll be quite different.

Of course there is also Wikipedia, where users can add content…

User content is going to be increasingly significant. A great deal of it will continue to be partial, ignorant and ill-informed, as it already is. And there will be more room for the lunatic fringe. It’s a bit like having proportional representation in an electorate.

In England, which is a profoundly democratic country, we have a deeply undemocratic voting system—fortunately. First past the post, wins. Everyone else doesn’t matter. Either you win or you lose. If you win, you’re in. If you lose, you’ve had it. Which means, lunatic fringe parties get nowhere.

Now if you are a democratic society and if you have the web, however lunatic or fringe you may be you can scream and shout as loud as you like. In theory, that’s a great thing but in practice it’s not, because it encourages maniacs of every description to make much more noise than they deserve.

I’d like to revisit the 2012 Olympic logo. You quite rightly say that this is for the generation to come. But it’s only a few years away. Will this logo alienate the older generation because it is so focused on the coming generation?

The older generation always get alienated. I mean people from my generation are always walking around saying things were much better when they were younger. But I don’t agree. If anything, things were much worse when I was young.

If you read any novel from, for example, the late 19th Century you’ll see how much better people thought things were in the early 19th Century. Or you can see early Victorians talking about how much better Georgian society was. Old people think young people are hopeless and young people think old people are kind of half-witted, which may well be true [smiling].

You also mention in the introduction to your book ‘Wally Olins: The brand Handbook’, that: ‘A brand is simply an organization, or service with a personality.’ Is branding easier or harder to achieve with actual personalities at the helm of a company, the most obvious example being Richard Branson?

It’s much easier at one level because you can focus on that personality and people can recognise that person. But it’s also much harder because the personality is not everybody’s choice and also you can’t control how the personality behaves.

If you’re looking at Nation branding, and that whole area, in which I am very much engaged, you can see how perceptions of the United States have changed in just a very short time. Right now as we talk in November 08, 2008—Bush is bad, Obama is good. [Both laughing.]

Now clearly [laughing] that is so simplistic in relation to a country like the United States as to be laughable, I mean we both laughed when I said it. But personalities are incredibly important in making imagery really palpable for people. But they are very dangerous because they are hard to control. You don’t know what those personalities are going to do.

Take for example Michael Jordan for Nike: suppose he turns out not to be such a nice chap after all? So I’m personally, very, very, [pause]… ambivalent about the use of personalities in the development of brands—very ambivalent about it. Other people take a more sanguine view.

You mentioned Barak Obama. In The Wall Street Journal recently, when John Maeda commented on his new role as president of the Rhode Island School of Design he stated: ‘the president is the human logo (of a school)’.¹ If this is the case, one could argue the new president elect Barak Obama has, and will continue to dramatically change Brand America. Would you agree?

Well it depends of course on what Obama does but it will change perceptions about America hugely. You can’t look at any major country without seeing the leading figures for those countries because they are figureheads.

[The Russian President, Dmitry] Medvedev is seen to be the puppet of Putin. And Putin is still seen to be in charge. For better or for worse that is the way Russia is perceived. The President and Prime Minister of Lithuania don’t matter much because nobody knows them outside Lithuania, and there may be a few places where people don’t know them inside the country either, but not very many…

[Laughing] You mentioned you are involved in the branding of Nation States. Do you think countries really need to have branding? I understand that we can think of Britain and The Netherlands and Japan and we can recognise their values, traditions and culture. But this perception isn’t manufactured in any way. It happens organically and by its own accord. So do you think a manufactured branding process, for an organically established national identity, is necessary or good?

Well, the first thing is: it happens anyway. So whether you attempt to manage it or you don’t attempt to manage it, it’s there. All things being equal, you are more likely to be influential if you attempt to manage it as opposed to not doing so. That’s the first point.

The second point is that you can reasonably assume that the branding process within most countries is not really managed well because all the people you are going to deal with are so consumed with their own area of activity, whether it’s tourism, brand export or foreign direct investment, and so jealous of everybody else’s area of activity, and so determined to hang on to budgets and power, that they don’t cooperate much.

Even if you don’t like [the idea of branding countries], you can derive some satisfaction from the thought that it doesn’t work very well. However, there are some nations that, broadly speaking, have a perception that is kind of in line with the reality. Many, however, don’t. The perception is out of date because the reality has changed.

Poland is an example of a country which has changed dramatically over the last 25 years. But the perceptions of Poland are still stuck in the eighties and early nineties—they have not changed sufficiently. And that does affect tourism and inward investment and brand export and its proper that perceptions should be changed to align with a changing reality.

Malaysia is an example of a country where (whatever you choose to call it) the ‘country of origin’ effect is more or less negligible. The shirt doesn’t increase in price if it has the label ‘Made in Malaysia’ appear on it. I mean, at a very simple level, if it did help to have ‘Made in Malaysia’ on the shirt then Malaysian products would earn more foreign exchange and that would help the economy of the country.

So there are issues here [in relation to branding countries] to do with economics, with finance, with inward investment. There are issues to do with culture. There are issues to do with understanding and misunderstanding. I mean, I’ve got some research about Germany and about America, and about Britain, and when you look at the misperceptions you don’t know whether to laugh or cry. And it’s better if one tries to deal with these.

So there are issues here [in relation to branding countries] to do with economics, with finance, with inward investment. There are issues to do with culture. There are issues to do with understanding and misunderstanding.

[Laughing] You mentioned the cultural aspects and the understanding and the misunderstanding between countries. There is a design consultant [Simon Hong] based in Sydney who has recently branded Abu Dhabi. In your opinion, how can someone who is not immersed in that culture, who doesn’t live there, how can they brand a city or a country?

Well, your example relates to a country which is an artificial construct. Dubai, Abu Dhabi, all those Gulf countries are new. They didn’t exist before. They emerged through the discovery and development of huge natural resources.

But the question you are asking is: how can a foreigner understand a nation with whom he/she has no kinship? First of all, if you’ve got any sense, you don’t work alone. You bring in expertise. You read some history and you work with people who understand the country a lot better than you, or who are much closer to it than you are. You work with historians, cultural experts, business people and that way you get to understand the country.

I like it because my training was in history, and I read a great deal of history and have a strong interest in anthropological and sociological matters. I like it and I enjoy it, and I think I am quite good at it [smiling].

[Smiling] I guess the other side of the situation is that being a foreigner provides some objectivity. In this instance one has no ties to a perceived tradition, which has to be projected…

Precisely. And if you have—I guess you could say, ‘courage’—you say what you think. And people inside the country find it hard to be objective, whereas those outside the country might find it easier to be objective. A certain amount of charm and brutality goes down as well. One needs that mixture [laughing].

[Laughing] As a matter of interest, now that we are talking about countries and branding, what are your views on Brand Australia?

[Pause] I think it is one of the less unsuccessful efforts. I don’t think I could go quite so far as to say it is very successful because very few nation branding programmes are. But I think it is clever. I think it gets to the point about Australia, this kind of brash, self-confidence… I think it is rather good.

No doubt there will be many Australians happy to hear that it is—as much as it can be—a successful brand.

Now, you mentioned the current global economic downturn in a previous conversation. Usually, when times are prosperous, branding, advertising and design are pretty much in favour because these are perceived as a luxury, which companies can afford. In today’s financial climate, priority lists in companies will change and the ‘luxury’ communications services may well fall to the wayside. In your opinion, do you think that branding and communications are more essential in an economic downturn, or is it justified to cut these from the company priority list?

I think if I was talking to a large newspaper, or if I was on television or the radio, and someone asked me this question my answer would have to be ‘now is the time when you have to spend more’ [smiling]. If you want the truth, if you want to know what I really think: being cautious at this time, for most companies, is sensible—until things settle down a bit.

Nobody knows how deep this crisis is going to be, how long it’s going to last. Nobody knows how consumers are going to be affected. Nobody knows whether this will profoundly change the spirit of the times—nobody really knows.

But, because I am an entrepreneur, I have to be optimistic, as entrepreneurs are. So my inclination is to think that the crisis is not going to be as long or as deep as people think. But that’s possibly wishful thinking.

If I were in this situation and I were running an organization where I didn’t actually need [branding and design] right now I’d say: “I’m going to wait for a few months and see what happens”. And that is what is happening with many of our clients. That’s the bad side or the reverse side of the coin.

The obverse side of the coin is that so many companies have gotten themselves into so much trouble, particularly in the financial services sector, that if they are going to try to regain trust they’re going to have to, if you’ll forgive the expression, rebrand themselves. They’re going to be doing different things, or the same things in different ways, and they’re going to have to—to coin a John Major ² phrase—‘Get back to basics’. They’re going to have to stop bull-shitting and start trying to regain trust. A certain amount of humility wouldn’t do any harm, either. An apology wouldn’t be unwelcome.

Some of these financial services companies will be doing slightly different things in slightly different ways and will have to project a different idea of themselves. Some will be merging and acquiring. My judgement is that Relationship Management will come back into demand. If we’re talking about high-tech and high-touch, high-touch is going to come back and high-tech is going to be more subordinate. That means financial service institutions are gong to say: “Look, we’ve got a human face after all—look at that!” And that’s going to entail a bit of rebranding.

So it isn’t all bad news. In fact, we’re actually working for a very large financial institution right now on a major rebranding programme.

Of course, it’s very difficult to put a value on a brand, to decipher its equity and worth. Perhaps it’s similar to the world of art where Damien Hirst believes art “is only worth what the next person will pay”…

That’s my view entirely. I think these econometric measurements about the value of a brand are utterly worthless. I know people love them. I know people want to put them on their balance sheets. I’ve written about this in my new book (Wally Olins: The Brand Handbook).

I think these econometric measurements about the value of a brand are utterly worthless.

I don’t know what the econometric brand evaluation of Lehman Brothers was in July of 2008, but it certainly wasn’t the same as it was in October. Organisations like figures. They think they are ‘facts’. But many of these so-called facts are not facts at all. They are facts in inverted commas—they are faction. They are an attempt to quantify the unquantifiable.

There is only one way to determine the value of a brand: How much are people willing to pay for it? There is no other way. The rest is a chimera, a mirage.

The idea that a brand is an asset is one of the reasons why accountants have trouble…

Of course it’s an asset. It’s a huge asset. But it doesn’t mean you can precisely value it because it can be struck by lightening any time. It is not a piece of capital equipment. It is an intangible asset, which means exactly what it says-—it is literally intangible.

Like market shares that are driven externally by forces beyond one’s control…

Exactly. And, you see, one of the problems we have is that business is dominated by organizations like McKinsey,³ who believe that if you can’t quantify it, it isn’t real.

Well, if you took that view, you can forget about music, and art, and Shakespeare, and theatre. That view is absurdly rationalistic. But if you go to business school—I teach in business schools—they’re trained to quantify the unquantifiable.

I’ll finish on this question. In your most recent book Wally Olins: The Brand Handbook you say that: “branding in the 21st Century will become increasingly important, not just for commercial reasons but for cultural reasons and a sense of place, as well as differentiating ourselves and our aspirations from those around us.” Do you see this as being important for companies and organizations or does it extend to a wider view, for example countries, cities and individuals?

Oh, countries, cities and individuals. I think branding is a phenomenon that… I said somewhere or another that: Branding is the greatest gift that commerce has given to culture.

I think increasingly, the next four or five decades will be important for cultural branding. If you look now at the way huge cultural organizations are becoming global, for example The Louvre in Abu Dhabi, or The Met. Now I’m not suggesting that it’s all good. What I am saying is that whatever it is, if it can be made more accessible to people it will be done through branding. So sport, the arts, culture, universities—for example, three or four universities now have campuses all over the world. These aren’t campuses in the traditional sense, they are franchises—the word ‘Columbia’ or ‘Harvard’, or whatever it is, will be treated as a franchise in the same way ‘McDonald’s’ is. That is a rather overworked way of putting it, but there is truth in there.

But that does not mean the world will become homogenous and bland because, however globalized the world is or becomes in terms of universities or McDonald’s, or whatever, there are always new people and new companies and new ideas that pop up.

If you want to have a little instance of this, Wolff Olins is now part of Omnicom, so in a sense it has become part of a major communications empire. But my colleagues and I have started something else, which isn’t like Wolff Olins. Or at least if it has certain characteristics of Wolff Olins it also has certain characteristics that Wolff Olins couldn’t possess because we are independent. All the locations are part of one office—no profit centres. You can’t do that in a big company. How do you make it work if there are no profit centres?

Of course you can also have an icon, for example the Sydney Opera House building, which can work as an extension of the organization’s identity, become a brand in itself, or be part of Brand Australia…

Or the Guggenheim in Bilbao—all that kind of stuff is going to happen, all of the time. So I don’t think we need to worry about the future of branding. It certainly won’t be bland!

Image credits:

Wally Olins portrait provided by Wally Olins

Abu Dhabi identity / Shutterstock