Patrick Muttart, Director Corporate Affairs for Philip Morris International, takes us through a new, dramatic and ambitious business model for the company with a vision to design a smoke-free future.

Note: This interview took place in late 2017 and refers to specifics from that time.

Kevin Finn: The Home Page on the Philip Morris International website states the organisation is “Designing a smoke-free future”, which places the business at an interesting intersection. Can you elaborate on this new direction?

Patrick Muttart: Well, we’re all participants in a consumer‑led, technology‑enabled product revolution, one that has the potential to both improve public health, while still preserving people’s freedom of choice—their personal freedoms. I think that’s quite important.

But to understand where we’re at today it’s good to provide a bit of historical context. If you asked most people today about tobacco and where it stands, in terms of societal acceptance, most people believe there was a time in the past when everyone smoked. Smoking was popular. Smoking was acceptable, but there has been a downward trajectory of popularity and acceptance. That’s the conventional view with most people. When in fact, the history of tobacco is a very complicated one, with peaks and valleys over the centuries.

People have smoked for a very, very, very long time. I mean, some suggest that it goes back to well before the time of Christ, with indigenous peoples in the Americas. And the tobacco industry as we know it—the modern tobacco trading industry—is about 500 years old. But what’s so fascinating is it’s always been controversial. I mean, you had characters like, Pope Urban VII, who doled out a sentence of excommunication for people who smoked. You had Sultan Murad IV, of the Ottoman Empire, who gave out death sentences. And even King James VI, from England in 1604, he wrote his famous The Counterblaste to Tobacco, where he articulated and advocated a number of the same attacks you hear today against tobacco smoking. Now, rather than giving out excommunication and death sentences, the English Monarch realized that, as much as he disliked smoking, it was a very, very good source of revenue. So his way of [laughs] attacking the problem—without attacking smokers—was to tax them, not to kill them.

So you know, acceptance was kind of up and down. But it wasn’t until after World War II, and more specifically the famous reports of the Royal College of Physicians in the UK in 1962 and the American Surgeon General in 1964, where opinion, at least the lead opinion at the time, began to consolidate around the view that smoking tobacco was harmful to health. This led to people in the street—but not just in the street, also people in governments around the world—who began asking: “Is there a better way? Is there a way to reduce the harm associated with smoking, but still allow people to partake in an activity which people have been partaking in for a very, very long time?”

Initial thinking was that the power of science and technology could take smoke, isolate the bad parts of it and remove them. That way people could continue enjoying tobacco smoke. Government scientists, university researchers, and medical professionals discovered that the chemistry of smoke is extremely complicated; you just can’t go in and identify the bad stuff and remove it so people can have a reduced‑risk smoking experience. So, the thinking over time began to move away from fixing the smoke towards eliminating smoke altogether. What’s interesting about this is that it wasn’t until 2003-2004, where a Chinese pharmacist…

Yes, Hon Lik, who was looking to kick his own smoking habit, invented the first e‑cigarette. The idea was to take liquid nicotine, put it into a heating system to create a vapour which gives people the flavour and ritual of smoking—and delivers the nicotine. And that was the beginning of the e‑cigarette revolution. Interestingly, this is not a product invented by big business or ‘big tobacco’. It was literally a Chinese pharmacist acting out of his own self‑interest. He was also looking to develop something that could possibly benefit other people like him who were facing the same choice.

Referring back to the text on the Philip Morris International website, it states the business is now fully engaged in designing a smoke‑free future and that it will move out of the cigarette business. Given what you’ve just said, it’s still a huge turnaround. So, what prompted this complete, deliberate reversal? How long has it been in the making? Do we go back to 2002, 2003, 2004—or is it more recent?

Our company starting this in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s. People like the pharmacist in China were thinking about how to heat liquid nicotine, and we had started to look at whether or not there was a way to heat tobacco to the point where it produces some e‑cigarette‑like vapour but delivers the taste of tobacco, something that better represents—or better mimics—the ritual of smoking.

So, we launched a product in the late ’90s which flopped. We launched another in the mid‑2000 called Heat Bar, which was a heated tobacco product. It actually debuted in Australia. But it flopped, too…

That’s interesting, considering that ‘heat‑not‑burn’ products are becoming more popular now. The product you just described sounds similar to these…

I think what’s happened to both ‘heat‑not‑burn’ and e‑cigarettes is that some of these trends had been impacting other industries in a positive way and are now starting to impact and benefit the tobacco industry. One of the biggest impacts is the growth in the power and energy density of batteries. So we now have these devices which have the energy and the power to keep products—be it a tobacco or liquid nicotine—to a sufficient level for a sufficiently long enough period of time in a size that is portable and convenient for most people.

These technological innovations have made mobile phones smaller, cheaper, more reliable, and better. A lot of those same technological trends are positively impacting e‑cigarettes and heated tobacco devices. On top of this, you also have the growing consumer acceptance and demand for these products. Of course, with the proliferation of digital media and peer‑to‑peer social media, you have this explosion in smokers talking to other smokers—and not just spreading the word about these types of products, but evangelizing about them.

So, the societal changes, coupled with the technological changes, have taken these products from non‑consumer friendly, big, bulky things that no one would actually want to use on a day‑to‑day basis, to incredibly portable very stylish, reliable products that deliver what the consumer is looking for, which is basically the nicotine, the flavour, the ritual, but without the combustion, which is the source of most smoking‑related diseases.

So, the societal changes, coupled with the technological changes, have taken these products from non‑consumer friendly, big, bulky things that no one would actually want to use on a day‑to‑day basis, to incredibly portable very stylish, reliable products that deliver what the consumer is looking for, which is basically the nicotine, the flavour, the ritual, but without the combustion, which is the source of most smoking‑related diseases.

What struck me in my research is that e‑cigarette and ‘heat‑not‑burn’ products contain nicotine, which is the addictive chemical found in tobacco. They don’t have the carbon monoxide or tar, but is it intentional that Philip Morris International is moving to a ‘smoke‑free’ future as opposed to a ‘nicotine‑free’ future?

Well, nicotine is central to the smoking experience much like alcohol is central to the drinking experience. Is there a market for nicotine‑free e‑cigarettes? Yes. But it’s very, very small, in a similar way that the market for non‑alcoholic beer or non‑alcoholic wine is very small.

We’ve tried to be very frank about nicotine. I mean, nicotine is addictive. There’s no question about that, and we make no bones about it. But it’s not the source of smoking‑related diseases or illnesses. The problem with smoking, to put it simply, is the smoke. Hence, the focus on smoke‑free products. What’s interesting for us about this is, when you think about how all this fits into broader, public issues, we’re fortunate with tobacco because the component people want from our products is not the core source of harm—either physical or societal.

The nicotine isn’t causing the problems. It’s the delivery mechanism, which traditionally has been the smoke. Whereas, when you have things like alcohol, or gambling, or whatnot, it’s the actual core addictive thing that causes the problems, not the delivery mechanism. It’s not like it’s the water in beer which causes the products [laughs] to bring harm on itself. Whereas with tobacco, it’s the smoke and not the nicotine.

When you think about it, Philip Morris International is essentially seeking to rebrand an increasingly social taboo. Earlier you mentioned there have been ups and downs throughout the history of smoking. But in recent years there has been a dramatic push against smoking: Smokers have been shunted out of offices to smoke in the street, they’ve been corralled into small, confined areas in airports, and have been blamed for blocking up drains with cigarette butts—all of these things and more. Do you really think it’s possible to reposition Philip Morris International successfully in the time it’s going to need to do so?

Obviously, it’s going to take time—and it’s going to require some humility and prudence on our part. I think that’s one of the big things with the company; people who work in it are very, very aware of the reputational challenges we’ve faced with the governments, with regulators, with society. And we’ve made a very deliberate, very strategic decision to base this on science, to be transparent about the science, and to communicate in a way that is conservative and responsible. So, you’re not hearing us say these are safe or healthy. We make it very, very clear that these are reduced‑risk products, that they are targeted at existing cigarette smokers, and they should be compared against combustible cigarettes and not compared against breathing fresh air.

You’re not hearing us say these are safe or healthy. We make it very, very clear that these are reduced‑risk products, that they are targeted at existing cigarette smokers, and they should be compared against combustible cigarettes and not compared against breathing fresh air.

Now you mention it, is there an age limit on e‑cigarettes? I don’t smoke and never have, so I’m not familiar with how e‑cigarettes are sold. But if a minor was looking for an e‑cigarette—because it’s not a regular cigarette—is there a different age bracket for e‑cigarettes and heat‑not‑burn products?

There’s a patchwork of laws across the states and territories. But, generally speaking if you’re under 18, you shouldn’t be using these products and you shouldn’t be able to buy them.

Is it well regulated at the moment, or is it still in its infancy?

No, it’s very, very tightly regulated. But there’s very big loophole in Australia. The sale of consumer nicotine is regulated at a Federal level by the Federal Poisons Standard. Basically, the only consumer nicotine that can be legally sold is what the government calls “tobacco prepared and packed for smoking.” And at the State level there are a series of bans and double bans—and in some cases, triple bans on the use of e‑cigarettes.

But against this backdrop, you also have the reality that about 41 percent of Australia’s two and a half million smokers have tried these products, and about 7 percent of them use the products regularly. So, the question is: How can you have so many people using a supposedly banned product? And it really comes down to…

That sounds like Uber. [laughs]…

It comes down to the loopholes where there’s a personal importation scheme allowed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration and individuals can bring nicotine into the country for personal consumption with a prescription and up to a three‑month supply. This has created a massive grey market in Australia—and a puzzling form of reverse protectionism, where you’ve got Australian companies selling liquid nicotine into New Zealand and New Zealand companies selling it into Australia because we can’t sell the products legally domestically.

But funnily, you also get announcements on Qantas and Virgin flights stating you can’t use e‑cigarettes even though these products are basically banned. So, it’s a bit like the Wild West and one of the points that we’ve tried to make is, it’s really down to the government: “Do you want a controlled, regulated environment, or do you want a non‑controlled, unregulated environment for these products?” Because they’re already here and people are using them. You see it all the time.

I want to come back to the word “designing” because it’s featured prominently on the Philip Morris International website. It seems like a very deliberate and intentional word. How central is design to this new direction, and how will it show up, in practical terms, across the organisation? For example, does it mean that Philip Morris International is moving towards being a design‑led organisation?

There are three elements to the design. There’s obviously product design: designing technology-based products in a marketplace where we have multiple competitors, not the traditional three big multinational tobacco companies that we compete with in the combustible business. Secondly, there’s the redesign of the organisation to make it more agile, more entrepreneurial, more consumer‑centric. And finally, there’s the re‑design of the company’s relationship with government and the community. That’s where I spend most of my time as a corporate affairs professional—but while keeping tabs on all those three at the same time.

So, from a clearly product design perspective, the invention of the Bonsack machine—which was the first reliable, widely‑used, automated cigarette bench machine developed around the 1880s—the manufacturing process hasn’t really changed. I mean, you take top tobacco, roll it up inside paper, put into packs, and sell them through pretty conventional distribution channels. In this new world, we actually have to think about technology. We need to think about colours. We need to think about texture. We need to think about shape. And like any technology company, we need to strike the right balance between form and function. This is a profoundly different type of environment for our company.

Of course, we’re also exposed to a number of new insurgent competitors popping up all over the world and the realities of this new type of product flow into the new business model because, as an organisation, we need to be much more attuned to where consumers are at. More importantly, we need to know where are they going on many of these design questions. We need to get into the business of customer care, hyper‑care, call centres, warranties. I mean there’s all this stuff, which was never a factor in the old, conventional tobacco business.

In this new world, we actually have to think about technology. We need to think about colours. We need to think about texture. We need to think about shape. And like any technology company, we need to strike the right balance between form and function. This is a profoundly different type of environment for our company.

That’s going require a dramatic cultural shift…

No, it’s a massive cultural shift for the organization. And it means recruiting a new type of employee. It means creating new ways of working. It means being an enterprise developing minimal viable product, which you hear about in so many other sectors. This now needs to be applied to the tobacco sector. And I think, most importantly, it involves a change in outlook where everyone needs to be far more consumer‑focused and consumer-centric.

Changing things a little bit: the cigarette industry has been aided over the decades by how Hollywood, in particular, romanticised smoking. Then there’s the numerous advertising campaigns, which have also been celebrated the world over for their clever and creative ways to help sell cigarettes and smoking. Those ads have been instrumental to the success of many cigarette‑producing organisations. However, in another dramatic reversal, recently a US Federal Court ordered cigarette‑producing companies, including Philip Morris USA, to pay for factual ads that state the harmful effects of smoking, including an admission that cigarette‑producing companies intentionally designed their products to be more addictive. This comes after a 19‑year legal battle with the US Department of Justice, meaning it’s been forced upon an unwilling cigarette‑producing industry. So how does this impact the new vision for Philip Morris International? Does it erode trust? I mean, it’s got to harm the reputation further…

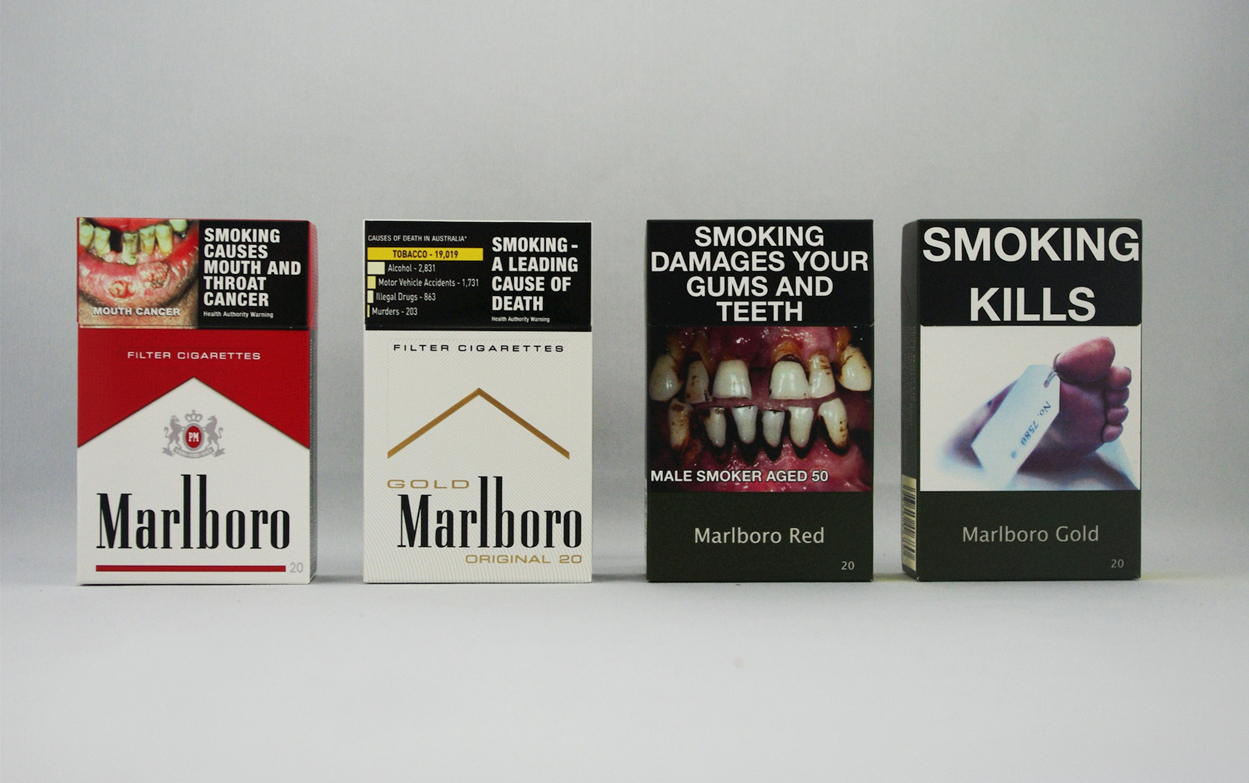

I don’t think it’s going to impact the reputation. There has been deep and widespread public awareness of the risks and the harms associated with tobacco smoking for a very, very long time. And in a country like Australia, there have been mandatory health warnings on packs (inside the leaves) from the early 1970s. When developments like these in the US occur it doesn’t directly impact Philip Morris International because they have been part of the decision. Incidentally, Philip Morris International and Philip Morris USA have been separate companies since 2008.

Of course, it certainly isn’t helpful because it involves the community in the discussion about the past whereas we’re trying to move the debate forward—to the future—where we’re saying our customers are changing, were changing. And this is due to the technological changes and scientific innovation, where we now have an opportunity to turn the page and to move on to something that’s new and better.

That’s one way to view it. But, as you mentioned earlier, Philip Morris International will need a bit more humility moving forward, and maybe part of that is to reconcile the past before you can move onto the future because there is obviously a reputation and issues around trust. Given there was such a long battle against this ruling in the US—and also against the plain packaging laws in Australia—I guess the perception is that cigarette‑producing companies or the tobacco industry generally, have come kicking and screaming to this societal shift—reluctantly. Now, that might not be the case, but that’s a widely held and strong perception…

Yes. And that’s what we have to work on. This is going to be something that plays out day‑by‑day, week‑by‑week, month‑by‑month, year‑by‑year. There’s no quick fix. There’s no silver bullet. We can’t change the past. But I think we can go to government, the media, the community, and simply point to what we’re doing today and to demonstrate that this is not window dressing. It’s a fundamentally new vision for the company, it’s a new operating model for the company, and it’s where we’re putting the bulk of our resources moving forward.

That will be necessary because, on the Philip Morris International website it states: “Society expects us to act responsibly and we’re doing that by designing a smoke‑free future.” So, while that indicates all eyes are on the future, there will be a transition period—long and hard, I’m sure—to move the conversation away from the past, which is a debate based on facts, as opposed to a future which is currently being designed. In saying that, it does take courage to include this admission on the website because it’s a statement intent and expectations will have been set…

It’s not easy. I mean, every time someone like myself does a media interview or delivers a speech to a group, it’s tough. Every time you stand for a one‑on‑one interview, or a one‑on‑one meeting with a public official, it’s tough. They’re wired to be suspicious. Their skepticism is obvious, and the onus is on us to demonstrate that we’re changing. And we’ve gone into these engagements with eyes wide open. We know exactly what we’re getting into. And we know it’s going to be a long, windy, bumpy road. But it’s one that we have to travel on. Having said all that, it’s also a lot of fun.

They’re wired to be suspicious. Their skepticism is obvious, and the onus is on us to demonstrate that we’re changing. And we’ve gone into these engagements with eyes wide open. We know exactly what we’re getting into.

Difficult as it may be, people like myself—and many of my colleagues working the industry—we do find it very satisfying. I would struggle to work in corporate affairs for most run‑of‑the‑mill corporations. I would find it quite boring. So, I think we are attracting a new generation of people who recognise the challenge. But they’re up for it. They relish the opportunity to have these types of conversations with the community, even though the conversations are not always easy.

I guess the suspicion and skepticism people bring to those conversations are, in many ways, well‑founded. But, on the other hand, there is a huge opportunity for the organization to embrace the reality, run with it and meet that challenge. This seems to be what’s driving a new dynamic culture, which appears to be emerging in Philip Morris International.

Yes, you’ve characterised it very well.

Just out of interest, I assume Philip Morris International will continue producing tobacco products during this transition because, particularly in Asia, Eastern Europe and developing countries, they’re amongst the highest cigarette consumers. So how is Philip Morris International going to manage this: On the one hand, stating you’re designing a smoke‑free future while, on the other hand, continuing to produce tobacco products for these markets? Or has Philip Morris International completely stopped producing tobacco products at this point?

The World Health Organisation projects that, a decade from now, there will still be a billion people who smoke. Smokers are not going to go away. And while this transition is underway, we believe it’s important that the market is serviced by legal, tax‑paying, fully‑compliant companies. If we were to get out of it—and our major international competitors were to get out of the business—smoking wouldn’t disappear. It would be dominated by the black market. So, the challenge for us is to meet the needs of our existing consumer base by making it very, very clear that we believe that smoke‑free alternatives are the better choice and to do everything in our power to convert the marketplace. That takes time at first, but as we’ve seen with other types of technology, once these things catch on, once people realise there’s a better way, an easier way, a safer way to do something, they often move—and they move very quickly.

Of course, with technology, particularly in the e‑cigarette and the heat‑not‑burn category, that’s going to impact the tobacco growers within the supply chain around the world, many of whom are in developing countries. What does Philip Morris International have in place for them?

They are our business partners. And there is still going to be a need for tobacco. The nicotine that goes into to e‑cigarettes comes from tobacco. Products like IQOS, heat sticks and cigarettes contain tobacco so tobacco farmers around the world remain business partners. And they will come along with us on this on this journey.

Speaking of developing countries, you recently moved to the Philippines. So, what obstacles for championing this new Philip Morris International vision in Asia are ahead of you, where smoking can be seen as part of the culture in some instances?

I think—as is the case with a number of consumer products, particularly consumer electronics products—the places where they first gained popularity are countries which are affluent and technologically advanced. And in the case of e‑cigarettes and heat tobacco products, the countries where people first begin to look to and embrace these products are places which are affluent, which are technologically savvy and and health conscious.

And particularly Japan and South Korea, I believe…

Yes! And where you’ve got the added dimension of hygiene being incredibly important. You know, in Japan you never see people smoke, but one of the most popular accessories is the portable ashtray.

Really? That’s interesting…

I believe it’s because it’s considered socially unacceptable to even drop ashes on a sidewalk. So people collect their ashes. They zip up their portable ashtray, and then they dispose of the ashes at home. So in a market like Japan, you’ve got this additional element where people really like the fact that these products produce no smoke—because there’s no ash, and there’s less smell.

Two other benefits, which are not discussed a lot but which are central to the experience, is the fact that these products are also safer within the public safety sets, considering how many fires get started by inappropriately discarded cigarette butts. We’ve moved to a non‑combustible product, which dramatically reduces fire risk, in addition to your personal health risk.

It’s a benefit to people in the surrounding area too, because passive smoking has also been a huge health issue for many, many years…

Yes, yes. And another thing—and this is something you observed—when people use heat sticks, because there isn’t a flame, it isn’t smouldering. People typically just slide it back into the pack. So, there’s a public health benefit, a public and a personal health benefit. There’s a public safety benefit, in terms of a fire risk. And it contributes against littering, especially in countries like Japan, where cleanliness and hygiene is important. These additional elements really, really add to the value proposition. And it has been found to have contributed to the products’ success.

Now, with developing markets, the absolute first step is to start building awareness: Awareness of the fact that the company itself believes these products are a better alternative for our consumers; awareness within the population that these alternatives exist; and to demonstrate proof of performance in the developed world.

Of course, it’s also going to rely heavily on a deep awareness of cultural sensitivities too, just like we’ve discussed in relation to Japan. There’ll be different sensitivities for different cultures, different countries. And, as you said earlier in our conversation, this new vision is not as easy as ‘packing cigarettes into a box and going through supply chains and distribution chains’…

Yes, the approach will have to be localised. We need to approach these conversations with humility and respect—and not make it look like we’re some multinational corporation with its operation centre in an affluent, beautiful part of Switzerland, trying to impose a solution on consumers. So, it’s more about generating awareness, reaching an acceptance, giving people the products that they’re looking for, and adhering to them, in terms of what sort of alternatives work best work best for them.

The approach will have to be localised. We need to approach these conversations with humility and respect—and not make it look like we’re some multinational corporation with its operation centre in an affluent, beautiful part of Switzerland, trying to impose a solution on consumers.

Changing gears a little, Philip Morris International has built some pretty popular and iconic brands. In recent years, those particular brands have probably lost their influence, maybe their appeal and their attraction in some social groups. These brands have been incredibly valuable assets for the business. And this is probably an obvious reason why the cigarette companies fought against the successful introduction of the plain packaging laws in Australia. The campaign against the plain packaging ruling was argued vigorously by tobacco companies. Yet now, Philip Morris International is pulling out of the cigarette business altogether. So how do you reconcile those sorts of opposing positions, one vigorously defending packaging while also getting out of cigarettes altogether?

We oppose plain packaging because we genuinely believe it was regulatory overkill, and that it wouldn’t work. An not only would it not work, but that it would actually assist the black market. And that’s exactly what we’ve seen in Australia. Between 2013 and 2016, there hasn’t been any statistically significant drop in the smoking rate, yet the amount of illicit trade entering the country—or attempting to enter the country—has proliferated. And you see the emergence of counterfeit brands. Anyone can counterfeit, but it’s a hell of a lot easier when the government—on its website, communicating to the world—declares the exact product specifications: the font type, the font size, the Pantone colours for the packaging. This has been a gift to the black market. And the entities that have suffered are retailers, but also the government because they are losing over a billion dollars a year to the black market in tobacco products.

There’s no such thing as a safe cigarette, but when people buy it from us it’s regulated.

And the actual individual could be getting something far more toxic?

You never know what you’e getting with these kinds of products, or where they’re from, or how they were made. I mean, there’s no such thing as a safe cigarette, but when people buy it from us it’s regulated. It’s packed. Factories are inspected. A lot of these black‑market products are produced by fly‑by‑night operations.

But in terms of the branding, there was a very deliberate decision right from the get‑go to begin the process of building fresh, new brands, which we hope will become the iconic brands of the future. That was behind the decision to embrace IQOS as a platform brand for the devices. And in most markets, we’re introducing the tobacco sticks as a product called HEETS. In a small number of markets, we sell these as Marlboro heat sticks. But the intention globally is to build the HEETS brand, as well as some of the company brands for these products.

That wasn’t the the easy approach to take. It would have been easier to simply ride out the brand equity from the existing conventional combustible brands. But the company looked at this and said: “You know, we’re in this for a long run. We’re playing the long game here. And we owe it to ourselves—and to the future—to begin building iconic, non‑combustible brands that will stand the test of time.”

So, by creating a whole new set of brands, is the intention to disassociate the business from the brands which are attributed to some of those major health issues that are always being raised? Or is it that they’re such a different product, such a different category that it just makes sense to build new brands from scratch?

They’re fundamentally different products. So, the thinking was that these fundamentally different products need fundamentally different brands. And we made the decision to invest in building those brands. Now, that’s going to take time. These things are never… Brands don’t become iconic overnight. But this is where we’re putting our resources moving forward.

One of the big criticisms levelled at tobacco companies is marketing to minors. I know tobacco companies say: “No, we don’t do that”. But there’s a very grey area around marketing to minors—or at least appealing to minors. Is that something that Philip Morris International is going to tackle head-on with these new products?

Of course, we’re aware of the concern. And we certainly take the criticism seriously. It’s one of the reasons why the preferred approach to marketing for these new products is direct, you know, one‑to‑one communication with existing smokers. The overwhelming focus is creating these unique, one‑on‑one experiences where an individual can help the consumer with their conversion journey. And it represents a fundamentally different way of communicating about our products from the days of old when there were Marlboro cowboys on billboards.

This is driven by a principle—that this is a better way to market a product that is entirely different. But it’s also driven by necessity, in that these are consumer electronics products, which are complicated. You need to know how to use them properly. It’s not like a cigarette, where you just look at it and it’s pretty obvious how to use. For these new products, we need to teach people how to charge it. We need to teach people how to use it. We need to teach people how to clean it. And that’s much better suited to one‑to‑one communication.

With such clear and loud statements regarding Philip Morris International’s future business model, the organisation will be held accountable—internally and externally. There’ll be no hiding from these new goals and objectives, which the company has publicly set out for itself. While this is a welcome approach, how will Philip Morris International measure its success?

The company is going to be moving towards publicly announcing key KPIs so that employees, investors, partners, and the product community can track progress on this journey. But leaving the KPIs aside, it’s going to be pretty obvious—each and every quarter, each and every year—whether or not we’re making progress towards converting our consumer‑based smoke‑free products.

Do you think another one of those measures of success might be a warmer societal acceptance, in general?

That’s something we certainly want to attract, in terms of our reputational surveys. All companies, all industries do this. And we’re already starting to see results. But, it’s still early days, and I always say to my team and my colleagues that we’re playing a very long game here.

One of the things we’ve had to learn to say internally is: “I don’t know.” It’s a new world, and we face new challenges. It’s not like we can go back to the regular checklist, or the template, or the turnkey solution, or to the solutions we’ve used from the past. There’s a lot more questioning internally, and a lot more admitting that we don’t necessarily have all the answers. This is going to be a big exercise in trial and error.

Hopefully, we move the ball forward and we get to where we want to go. But certainly, there’s a renewed sense of purpose. There definitely is a new spirit within the business. And the onus is now on all of us to to deliver.

Image credits

Patrick Muttart portrait photography by Archie Gonzalez

Screen grab of a slide appearing on the Philip Morris International website Home page (2018)

Hon Lik smoking an e-cigarette by Wang Zhao/AFP/Getty Images

Big Tobacco Ad sourced on ABC, Australia

IQOS image by Philip Morris

Progression of cigarette packaging by David Hammond

Marlboro Man billboard sourced on Conclusion