Larry J Kolb—ex-CIA operative and best-selling author—shares his experiences working in the covert world of spies. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #5, which focused on the theme ‘Identity’.

Kevin Finn: Until your early twenties you resisted the secret world that your father was part of. Eventually Miles Copeland, one of the founders of the CIA, convinced you to join the agency, but you did so reluctantly. What changed your mind and was this a decision you came to regret?

Larry J. Kolb: Miles Copeland changed my mind. He was just so damned interesting, and charming. And by the time he finally let me know why he’d been spending so much time with me, what he really wanted from me, we were such close friends that I almost couldn’t conceive of saying no. Beyond that, he made what he was inviting me to do seem fascinating, which it certainly was. Regrets? I suffered some because of my decision, I learned some hard truths. But, no, I have no regrets.

Intelligence agencies employ covert tactics and personnel to gather information. What’s it like to be a spy or a covert operative in today’s world? Is it as gritty or as glamorous as the popular culture stereotypes lead us to believe: James Bond, Jason Bourne, Alias and Hollywood films depicting spies and CIA secret agents? Is there even a shred of truth in these depictions?

Espionage requires patience. What’s it really like? Vast, truly vast, stretches of mind-numbing boredom interspersed with some very interesting and sometimes heart-pounding moments that are absolutely not boring at all. In those moments—not the waiting, but the doing, in those interesting moments—a sort of hyperaware calm always came over me. I felt totally aware of everything—everything—that was going on around me. On the surface, I seemed my normal self, at least I hope I did. But beneath the surface, it was almost as if I was in some sort of altered state.

Espionage requires patience. What’s it really like? Vast, truly vast, stretches of mind-numbing boredom interspersed with some very interesting and sometimes heart-pounding moments that are absolutely not boring at all.

Part of that was a result of planning. The more I planned, the more time I devoted in advance to reconnaissance and to thinking through every possible outcome before I acted, the calmer I could be in the crucial moments—and that, at least for me, was very critical to my ability to perform. Is it gritty? Yes, sometimes. Glamorous? Probably less glamorous than the stereotypes would have you believe.

And yet I fit into those stereotypes better than most, because of the fact that the reason Miles Copeland recruited me was the glamorous circles I already travelled in, and the access I had as a result of that.

Similarities to James Bond? Well, yes, in my time in his profession, I wore a lot of well-tailored suits, and there was always a tuxedo packed in my suitcase. But that was my lifestyle before I met Miles, not something that grew out of Miles recruiting me, and not something all that typical for an espionage agent. I’ve still never seen a car with an ejector seat.

Jason Bourne? Car chases and big explosions make interesting scenes onscreen, but there’s certainly a lot less of that in the real espionage world than in the movies and on television. The idea is to get away without leaving a trace, and without a fight. Which, admittedly, isn’t as interesting onscreen as car chases and explosions.

Alias? Well, yes, there are certainly intelligence services whose offices and other facilities are hidden in plain sight amongst totally unsuspecting populations in major cities all over the world. However, the “intelligence work” portrayed in Alias never seemed very intelligent to me.

Broadly speaking, many ordinary people are familiar with the identities of legitimate Government secret agencies, for example the CIA, MI5, Mossad, and suchlike. However, do you know if there are any ‘secret’ secret Government agencies in existence, the identities of which are generally unknown to the wider public?

Yes, I do know. And yes there are many, many fully-sanctioned government intelligence services which fly totally beneath the public’s radar.

Over the last few decades there has been an increase in ‘identity theft’. Recently the ‘invitation-only’ website Darknet Market, an online criminal black market specialising in identity theft, was shut down after a two-year international operation involving various federal agencies. Obviously the criminal world operates in stark contrast to legitimate law enforcement agencies so, as a covert operative, how does one go about designing a convincing new or false identity?

Confidence and charm are still important, of course. No matter how good your documents and your backstory, you’re still absolutely screwed if you hesitate every time you introduce yourself by a false name. Try it; it’s not as easy as you’d think.

Confidence and charm are still important, of course. No matter how good your documents and your backstory, you’re still absolutely screwed if you hesitate every time you introduce yourself by a false name.

But, beyond that, the challenge is not creating a new identity, but backstopping it—building into both the public record and private records material, verifiable records that are consistent with a newly-created false identity.

Even today, with information so much more accessible than it ever was before, and with technology that gives almost every member of the public the ability to cross-check and cross-reference information in ways that twenty years ago only intelligence agencies with supercomputers could do, there are, of course, still ways to create all new and totally false, but seemingly verifiable, identities. And as your question foreshadows, identity theft is probably easier than the work that goes into creating and backstopping false identities.

There is a world of rogue secret agents we rarely hear about, those who use their training for malicious purposes and personal gain. A few years ago you helped track down one particular rogue agent, which you documented in your book ‘America at Night’. Your investigation involved navigating a labyrinth of various bogus identities, which had fooled all other agencies up to that point. How difficult is it to expose a well-organised and well-constructed false identity?

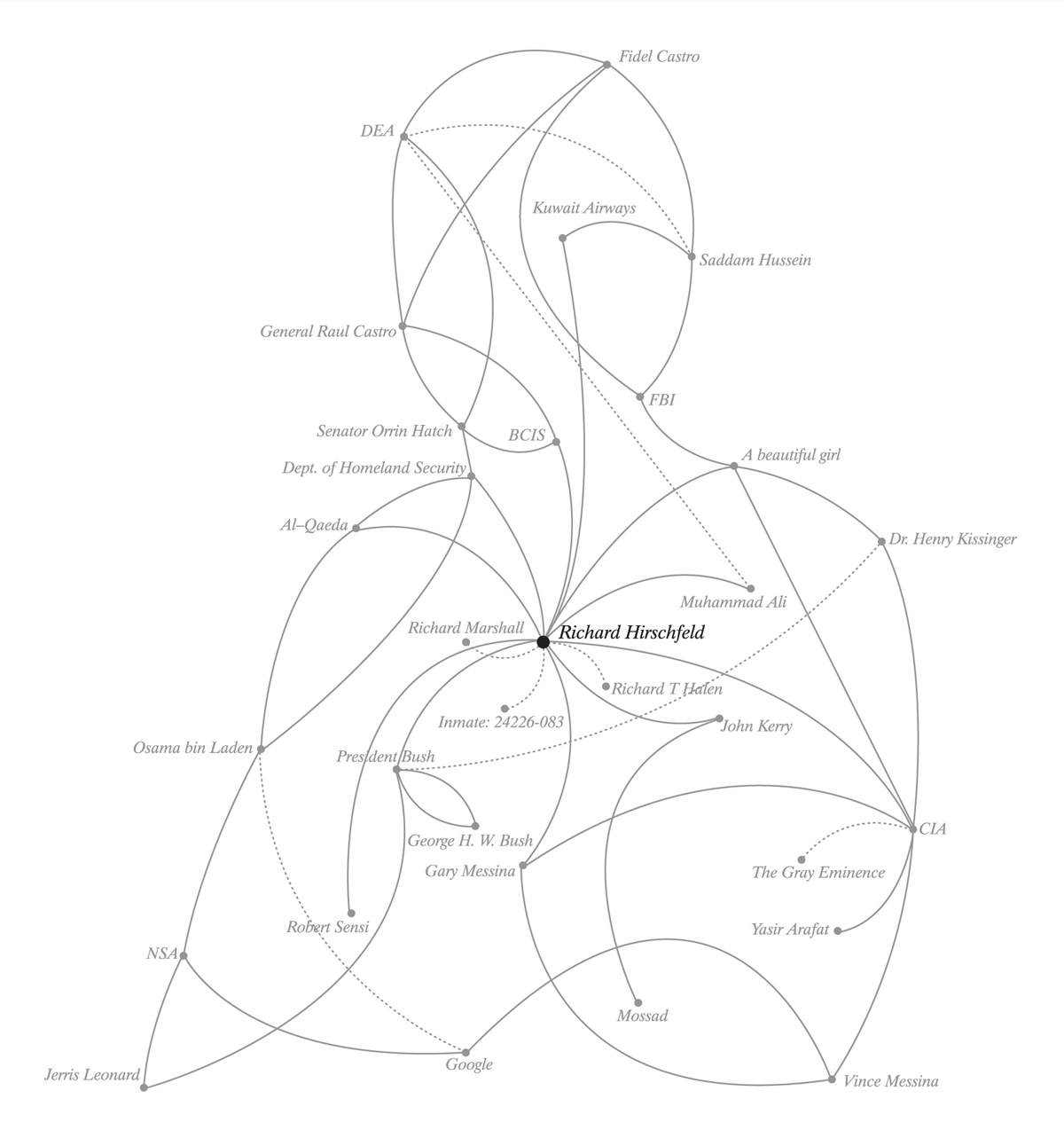

Apparently, it can be very difficult. In the case you mentioned—the case I recounted in America at Night—the Department of Homeland Security, the CIA, the DEA, the IRS, and other U.S. government agencies had been trying intensively but unsuccessfully for three years to discover the real identity of a former CIA agent who was going by the name of Richard Marshall. It didn’t help that all of the government’s databases had been wiped clean of information about the man who called himself Mr. “Marshall.”

And yet, a week after a friend of mine who was at the time a very high-level official of the Department of Homeland Security asked me to get involved in the case, I had solved it, identified the bad guy, and soon after that he was arrested.

How did I pull that off? It happened that I had known the guy, many years earlier, and I have a very good memory. What the U.S. government’s security services had somehow lost from their files, I still had in my head. And much of what I couldn’t remember, I had saved in my own files. And thus “Richard Marshall” became “Richard Marshall Hirschfeld” and once I had given the United States government enough information and evidence to verify that, it became a whole lot easier to find him.

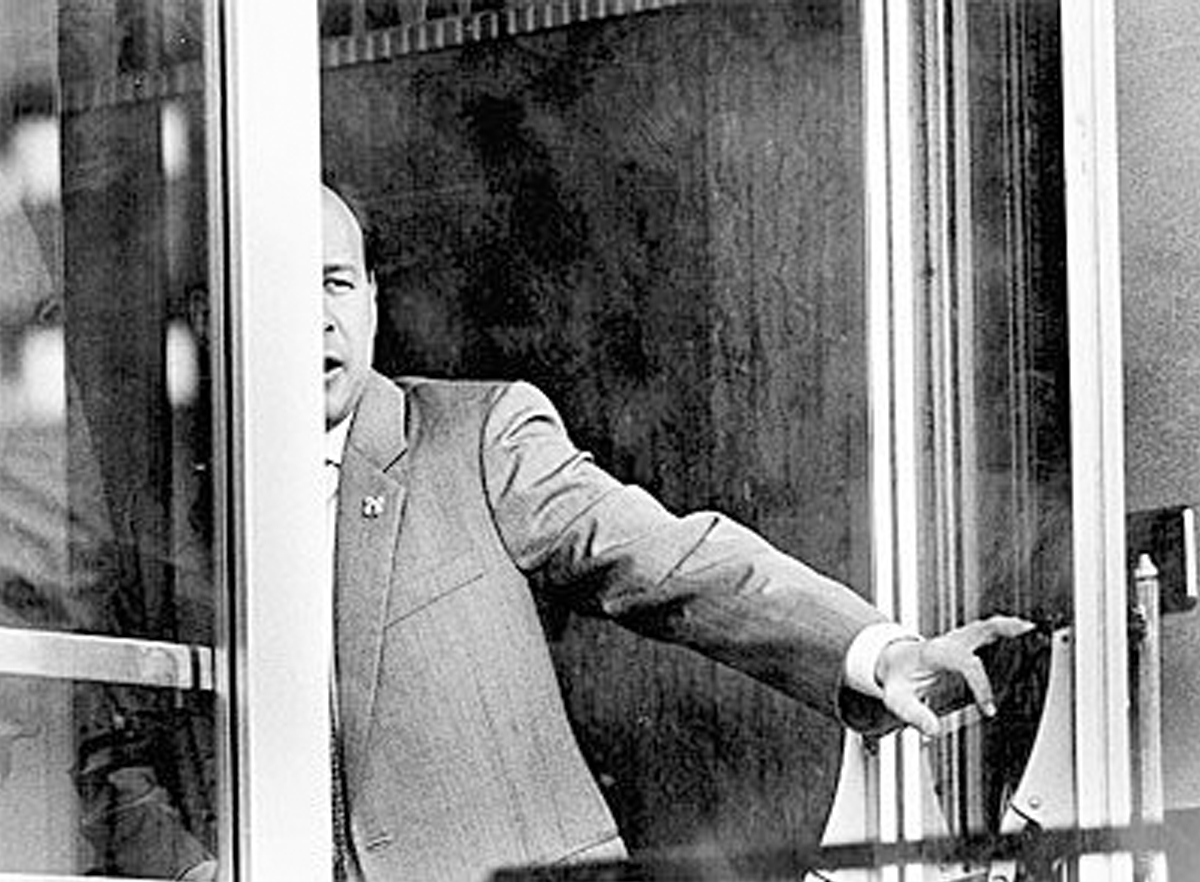

He was rather spectacularly arrested, in a safe house he had bought for himself using a corporate shell to attempt to conceal his link to the house. He then, even more spectacularly, and quite mysteriously, died, while in federal custody, while in the course of a campaign to tell every Washington power figure he could get word to that if the federal government didn’t release him immediately he was going to tell everything he knew about them.

Which brings us back to your earlier question about whether the real espionage world is ever as gritty as the popular stereotypes would have us think. In that case, yes. Richard Marshall Hirschfeld’s career as an intelligence asset and international intriguer did not end well.

In your opinion, can the media be used to engineer information for the public in order to aid covert agency operations or has the media become so efficient that it has evolved into another form of legitimate intelligence gathering? For example, in Keith Suter’s book ‘50 things you want to know about the world but were too afraid to ask’ it states: “during the Gulf War the CIA complained that the then President Bush didn’t need CIA briefings. He said he preferred to watch CNN live because the written CIA briefings took a day to arrive.”¹

Television news and other media can certainly be very immediate these days. Last year, at the Democratic and Republican National Conventions, the U.S. Secret Service was caught off guard by the immediacy of Twitter. The Secret Service found themselves learning details of the whereabouts and movements of certain candidates and others they were supposed to protect after audience members learned the same information through Twitter.

By now, that’s certainly been corrected. But as to the first part of your question, oh, yes, the media can be used, and very often is used, to engineer information in aid of covert operations.

With the Internet and immediate global access to information one could argue there is more transparency in today’s society. As a result, one would assume it is harder to hide. On the other hand, one might suggest it is easier to leave open but misleading trails. Does this make things harder for covert agencies or can they use this to their advantage?

Yes, certainly there is more transparency in today’s society, and that is a result of the amazing interactive technologies we have today. In intelligence gathering, technology has changed the way the game is played.

In intelligence gathering, technology has changed the way the game is played.

Just a few decades ago, to many people telephone answering machines seemed so inhuman and strange that most refused to leave messages on them. But that feeling soon fell away, and people began leaving messages for each other, and then responding to those messages with recorded messages of their own—without actually conversing one-on-one with the person with whom they were communicating.

The world had begun to embrace asynchronous communication. There was no longer a need to actually coordinate your schedule with another person’s schedule to have a conversation, of sorts, with them. And with the advent of email, asynchronous communication became the norm rather than the exception. That certainly lends itself to communications between espionage agents and those who control them.

We are understandably led to believe secret agents are incredibly protective of their identity and their covert status. With this in mind, what led you to write your biography ‘Overworld: The Life and Times of a Reluctant Spy’?

When I wrote my first book, I was on trial in India in connection with certain covert political operations I had been involved in for my friend Rajiv Gandhi—who, when I provided those covert services, was prime minister of India, and who, by the time I was tried, in absentia, had been assassinated. Indian press reportage concerning the case, and the trial, and me, was quite lurid. My cover was blown. And all my life, I’d wanted to be a writer, to write a book. So I did. And when the trial was finally over, acquittals all around.

In a previous conversation you once told me that one of the reasons you wrote your second book ‘America at Night’ was partly for your own protection. Rather than hide your identity from the rogue secret agents that you were exposing, would it be accurate to say you made the entire investigation public partly because being very open about your identity was critical to your safety?

Absolutely. In the beginning, everything I did related to the case I did anonymously, out of concerns for my safety. But then my identity was inadvertently exposed as a result of—how can I put it nicely?—let’s call it an “administrative mistake” made by a very high-level attorney and public official who had a lot of other things on his mind at the time and didn’t do a good job of protecting me.

From that moment on, I realized that the more people I told what I’d recently done and what I’d learned, and who was involved, the less likely I would be to end up mysteriously dead. At first, I just told the story to a lot of people I knew. Then I told a few well-placed reporters and asked them to make sure the story got out if anything happened to me. Then I told the story in a book.

I realized that the more people I told what I’d recently done and what I’d learned, and who was involved, the less likely I would be to end up mysteriously dead.

How does being a covert operative affect one’s own identity? For example, while you were a sports agent, most notably for Muhammad Ali, you were also involved with the CIA. Was the CIA just another aspect of your work or did you have to assume different identities for your CIA assignments?

In my case, I almost always used what’s known as “natural cover”—my real name, my real life story, the real access to certain halls of power that I had gained in the course of my life and my travels. On the other hand, when Richard Marshall Hirschfeld, for example, was arrested in 2004, he’d for the past several months been carrying five different mobile phones, each of which he answered with a different identity.

Politics are closely aligned with secrecy. American Vice President Dick Cheney once said: “One of the problems we have as a government is our inability to keep secrets.” In your opinion, is it important for Governments to keep secrets?

Absolutely. And Governments do keep secrets. Generally, the public hears only of intelligence services’ spectacular failures. The idea, as I said earlier, is to get away without leaving a trace.

Image credits

Larry J Kolb portrait photography by Maggie Steber

Illustration/diagram conceived and designed by Kevin Finn (in 2006, as part of a book cover proposal for Larry J. Kolb’s ‘America at Night’. It has been included in this interview at the request of Larry J. Kolb).

Richard Hirschfeld portrait, file photo sourced on The Virginian Pilot

Reference

1. 50 things you want to know about the world but were too afraid to ask, Keith Suters, Bantam, 2005, Page 166.