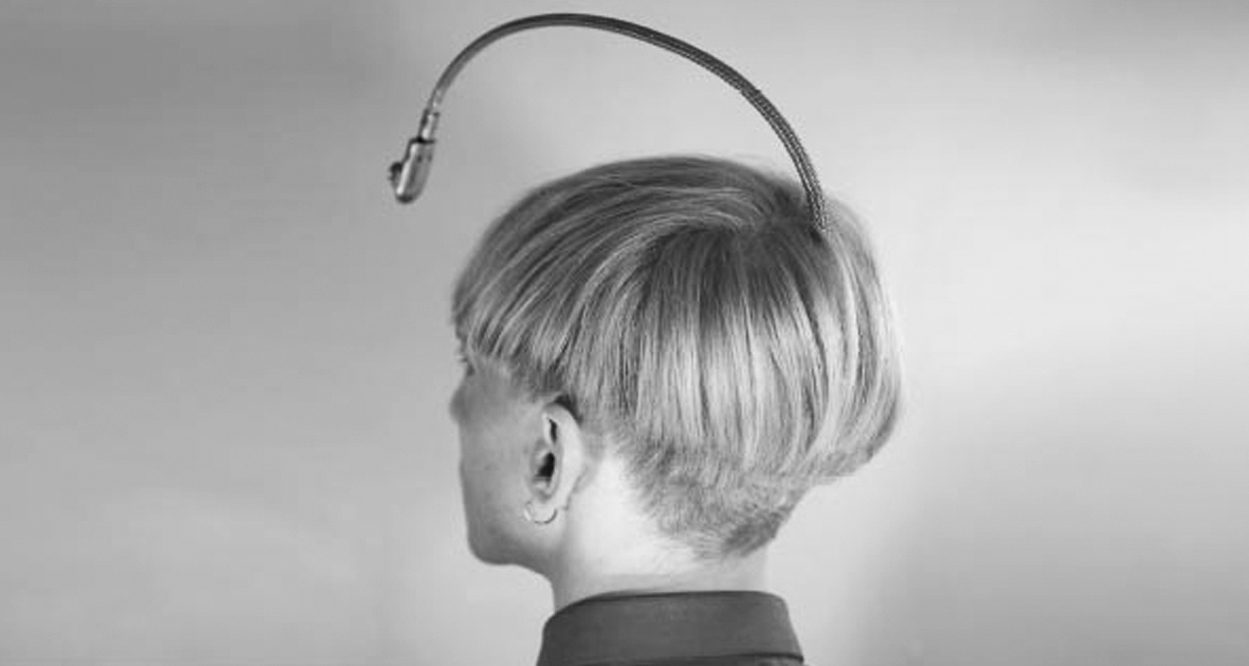

Neil Harbisson—a real-life cyborg—talks about the future of technology and cyborgism, which is cheaper and far less threatening then most people might think. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #8, which focused on the theme ‘Change’.

Kevin Finn: You were born with achromatopsia, a rare condition of colour blindness where you can only see in grayscale and where you can’t sense colour. I think the statistic is that it affects one in about 33,000 people in the world. For those who don’t know your story, how did you come to change the way you live with your condition? When did you decide to go through the physical change?

Neil Harbisson: When I was 11, I started different methods to receive colour. First I used people. I had a person for each colour. If someone said, “Blue,” I would think of a person that behaves like blue, or for “Yellow,” someone who behaves like yellow, because when you ask people to define a colour, it’s like they are defining a person more than a physical thing.

So, I had these different people and then if someone said, “Pink,” I would think of this girl who, for me, is very pink or, if someone said, “Red,” I would think of this boy who, for me, was very red—like passionate, aggressive words. All these elements that contain simple…

Characteristics?

Yes, characteristics. That was my first way of perceiving colour. Then I started using the piano, with each note of the piano being a different colour. When I was 20, I went to a lecture on cybernetics by Adam Montandon. It was then I realized that technology could also be used as a sense. That’s when I approached Adam and said that I wanted to extend my senses and asked if he could help, if we could create something. That’s how we started this project. I could decide how I wanted to sense colour—and I decided I would sense colour through sound.

You’ve set up The Cyborg Foundation which, among other things, supports the cyborg community. You must have a very strong sense that what you’re doing can truly help other people in similar situations. Is that something you’re actively pursuing, to promote a solution for other people with the same condition as yours?

It’s not people in specific conditions. We want to help everyone to extend their senses… Yes!

[Laughs]

We should all extend our senses; that’s what The Cyborg Foundation wants to do—to help anyone that wants to perceive more, to help them develop the sense they already have, but in a way that makes it a new sense.

And this relates to everyone, because there are many people who lack senses, but they don’t want more senses, for example many, many blind people or deaf people. There are even communities of deaf people who are defending the right to be deaf. Then there are people that hear perfectly well, but they want to hear ultrasound and infra sound.

There’s no relation between people who lack senses and people who don’t. It’s just people that want to extend their senses and people that don’t: they’re the two groups. Most are people that want extra, or more senses that go beyond the human senses. These are the ones who contact us.

In 2004, you had the bendable antennae surgically implanted in your skull. It works through bone conduction and allows you to sense vibrations. What interests me is you also had a chip inserted in your skull that allows you to access the Internet. How does that work? How can you be connected to the Internet?

It works in a similar way to how the sensor picks up light frequencies, and then transforms them to vibrations in my skull. The same system can be used to connect to other cameras, not just the one. It’s like a colour sensor, but it’s a camera. You can actually connect to external cameras if you have Internet.

That’s how I’m using the Internet. It’s actually Bluetooth in my head, so the Bluetooth can connect to any other device. If that device has the potential of receiving images, then these images can go directly to my head. That’s how I’m using it.

It’s actually Bluetooth in my head, so the Bluetooth can connect to any other device. If that device has the potential of receiving images, then these images can go directly to my head… It’s the use of the Internet as a sense.

Can you control that connection, or is it something that just happens? For example, does it constantly scan devices and pick them up if they’re available?

I can switch off the Internet connection, but I leave it on from 10am to 10pm so that I can receive colours from my friends.

There are five people that can send colours to my head, and I can also connect to NASA’s International Space Station every now and then. I’m training my brain to perceive the colours from space now.

The aim of the Internet connection is that I can be permanently connected to space. That’s how I’ll be using the Internet. It’s the use of the Internet as a sense.

That’s incredible! Many might describe how you sense as being similar to synesthesia. I know you’ve got a very distinct definition between how you sense things and how synesthetes might sense things, but can you describe the difference in your mind between synesthesia and your sense?

Synesthesia is the union of two existing senses, whereas in my case, it’s the creation of a new sense. That’s why I think it’s different from synesthesia—because I’m not uniting two senses, because I don’t see colour. If I could see colour, and at the same time be hearing the sound of it, then it would be the union of two senses, but I’ve never seen colour.

Synesthesia is the union of two existing senses, whereas in my case, it’s the creation of a new sense.

To me colour is a new sense. Also, I’m not hearing it through my traditional hearing sense. I’m creating a new sense, which is a vibration in my skull, which then becomes sound. Hearing colour is actually a secondary effect of the vibration, so the actual sense is the vibration, which is a new sense for me.

In both cases, it’s a new sense: it’s not hearing—it’s a new sense, because I don’t see colour.

In the era of wearable technology, you’ve said that you don’t feel like you’re using technology; you don’t feel like you’re wearing technology. You feel that you are technology. Can you expand on that?

Yes, the union between cybernetics and organisms, the feeling of being cyborg is more of a feeling, and I feel that I am technology. I don’t feel separated from it. It’s definitely a feeling. You don’t need to be biologically united to cybernetics to feel this union.

I know people that don’t have any cybernetics in their body, but they feel cyborg. I also know people that have cybernetics in their body, and they don’t feel cyborg.

Being a cyborg needs to be seen more as a feeling, in the same way that someone might have the body of a man, but feel that they are a woman. They need to be respected in this way. For example, if they feel they are a woman—even if they don’t have the body of a woman—they are a woman. Some of these people will have transgender surgery, and then they will become a biological women, as well.

What is most important is what you feel. I started feeling that I was technology very early, after a few months of hearing colour. It was more of an invisible union. The union between the software and my brain made me feel cyborg.

I started feeling that I was technology very early, after a few months of hearing colour. It was more of an invisible union. The union between the software and my brain made me feel cyborg.

You also refer to the fact that you get software upgrades. Does that dramatically change the feeling that you have, or is it literally a…?

Yes! Suddenly, reality becomes more intense or it mutates. When you upgrade your senses or when you add new senses, then your surroundings become new again. You are re‑exploring your context. It makes your context become interesting again. If you’re used to something, suddenly if you have a new sense, that becomes new.

Instead of exploring new countries or new spaces, by adding a new sense you’re suddenly exploring your reality again.

Visually, you stand out to people—not just because of your antennae, but because of your clothes. You often wear very bright clothing, because you’re wearing a particular sound that corresponds with that colour. I’m sure this draws further attention to you—visually. So, what has been the general reaction towards you and your appearance, and how has it changed over the past decade?

Yes. People shout things at me in the street, either for the clothes, for the antennae—or for the haircut. These are the three things that I’ve experienced.

[Smiling] People are very rude sometimes, or intolerant, but I’m completely used to it, because this has been going on for over a decade now. If I go out in the street something will happen, every day. It hasn’t changed in the last decade. What has changed is what people think the antennae is. That has certainly changed.

In 2004, people thought it was a light. In 2006, they thought it was a microphone, one of these chat microphones. 2008—no it was 2007—they thought it was a Bluetooth phone; handheld, hands‑free phone.

Then they thought it was GoPro. I think that was 2008 or 2009. Then in 2011/2012 people started thinking it was something to do with Google Glass. Now the latest thing was when a child asked me if it was a selfie stick. That’s the latest.

It’s always changing with the context of where technology is in the mainstream?

Yes.

So their perception is running with their understanding of present technology?

Hopefully, there will be a point in time where people will see it as a body part and as a sensory extension. I guess one day it will happen.

Because the context will change?

Yes! So they will ask what sense I am sensing. That still hasn’t happened.

Of course, this is now part of your identity. I know you had a challenge with getting your UK passport, purely from a visual point of view, because your photograph wasn’t going to be accepted. The UK government has now legally recognized you as a cyborg. Has that changed things for you in other ways?

In 2004, I had this issue and they didn’t accept my passport photograph. Then I explained to them about what I felt. I felt that this was a body part. But it went on and on. They didn’t like it. I insisted that I felt that I was cyborg, that I was this technology. In the end they agreed and accepted the picture.

This appeared in the local news, because I was in a very small town in England. Very small! Of course, people at the university knew what was happening. But I ended up in the local news and the journalists published it as something like: “UK’s first recognized cyborg.” That’s how the journalists defined it, and since then they’ve been using this term.

The result is that I can now legally travel, but I always explain what happened to me, and then people write it in their own ways.

It’s interesting how the media has defined you: the first legal cyborg. I imagine this has helped you in many ways. But has the media also hindered your story in any way?

Yeah, somewhat. Unfortunately, all articles have mistakes in them, but we no longer write to them and say: “Hey, this is not correct. You should change it.” We’ve stopped this because we realize it’s actually normal.

Some of them create these articles without ever even interviewing me, and then they write really inaccurate things, or extreme things. They’ve sometimes even quoted me, where I’ve never said the things they claim I have said, or they create this scary impression of me.

In the India Times they said: “there was a robot man in this country,”—or something like that. Some people create these types of articles just so that people will read them. Others do so because they like writing [the word] ‘first’ in articles, because then people read it, if you include a ‘first of something.’

I think they should stop this. It’s not necessary to create this or to use the word ‘first’ to create an interest in things. We’re not in the Olympic Games so there will be no first. We’ll all have our own things. We’re all different…

It’s not the same code of Olympic race?

No, exactly.

It’s interesting—with the prejudices you’ve faced, possibly as a result of popular culture and science fiction—what you, and others like you, represent could be scary, confronting or frightening for some people. How do you deal with that, the fact that you possibly represent a frightening future? How do you respond to that?

I don’t know how to deal with this. Many people feel threatened by individuals like me and The Cyborg Foundation, and they feel that we also go against God and against nature. Many people don’t really listen to what we say, because we’re not against religion.

I don’t think there’s anything I can do.

I receive death threats from people that are really against me. They even say that I should avoid certain countries, otherwise they will find me and kill me, and things like this. Some of them are really, really strongly against The Cyborg Foundation and against me. You can’t really talk to them. There’s no way for me to reply to these threats.

I receive death threats from people that are really against me. They even say that I should avoid certain countries, otherwise they will find me and kill me…

Of course people face racial prejudice, which is unfortunately still prevalent around the world, and we have it here in Australia. But when you look at the colour of people, you don’t distinguish between black or white or brown. You have identified a colour hue which is consistent among all humans, and it’s in the orange colour spectrum.

Yeah.

Do you think that could perhaps be useful in fighting racial prejudices around the world, because if we look at the universal colour of our blood, it’s red—it doesn’t matter what colour your skin is. Now, you suggest the human hue is also a similar colour. Is this something that could be used to perhaps remove some of the racial prejudices out there?

I hope so. I always try to mention this whenever I talk to journalists, and when I give talks. I always try to. I had also intended to include it in my TED talk. But that’s the paragraph that I missed out, because I was nervous, and because I couldn’t see the time monitor. There were some things I didn’t say in my TED talk, and that was one of the things. I felt it was really sad that I missed saying that. Now I keep saying it even more.

As I mentioned earlier, your antennae is now part of your identity. You’ve achieved what you set out to achieve—your personal objective to hear colour. It’s also influenced your art. And that’s also a big part of your identity. Now you’re a spokesperson for the cyborg community, and the cyborg movement. Is that something that has happened inadvertently, or did you set out to be a spokesperson?

No. I never thought I would be talking so much. My aim was that music should be my language. Then, suddenly, people started asking questions. I had to find answers. Then I was invited to places to talk, but it was never, ever my intention to talk. I’ve been pushed or forced to talk.

But I think it is necessary in some cases because it also makes the artwork feel closer to people in a way. The first talks I gave in 2004/2005, I was very shy. I didn’t know what to say. It’s difficult sometimes to share what you are experiencing, especially in the beginning. In the first big interviews I was really simple.

Journalists have basically created my speech, because they’ve asked so many questions. It’s thanks to them that I’ve thought about things. And questions from the audience always bring new thoughts.

It’s like real-time direct feedback, which you can then research if you need to, or respond to in a certain way.

Or think about, yeah. I don’t think so much about my identity or my senses. I’m focused on living. Then, suddenly, I stop and ask so many things. When I walk around the street, I have to talk to so many strangers every day. So, yeah, talking has become the main thing.

But it wasn’t at all intentional?

No.

You mentioned earlier about some of the prejudice you’ve faced, for example people saying you’re against nature. What I found interesting is that, ironically, when you were designing your antennae you specifically looked to nature for your design research. It’s like biomimicry, which can be a significant and influential driving force in contemporary design. We look to nature and say: “That works. We will replicate that.” Was the design of your antennae a long process for you to research?

Yes, it was long and it’s still going on. There’s no end to the design of this new body part. It can continuously evolve. For example, it’s not moving independently, so it’s like a dead body part in a way. It’s alive because it senses things, but it doesn’t move. But it should be able to move through thought. I should be able to move it without using my hands. That’s one of the next stages as a body part.

Also, the antennae’s energy should come from my body. These are two elements that are really important to the development of the body part. It’s still in development. And like many things, once you’ve achieved your aim, then suddenly your aim becomes a different one. I realize there’s no end to the body part or to the sense. Once you perceive certain colours and you’re used to them, you can then extend it. There really is no end.

Becoming a cyborg isn’t necessarily an expensive pursuit.

There is another surprising aspect to your research, which I heard you mention in London: Becoming a cyborg isn’t necessarily an expensive pursuit. People would think technology, biotech, all the names that we have for it, is expensive. In your circumstance, it wasn’t necessarily very expensive at all.

No. Most of the things I’ve mentioned are not expensive. They’re actually cheaper than an iPhone. This iPhone [pointing to phone] was really expensive. It was a lot! It has a lot of capacity. But you can actually extend your senses with $10 vibrations. For example, the technology in infrared hand dryers. You can take the sensor, create an earring, pierce it in your body and then feel vibrations if there’s a presence behind you. That’s very simple.

If you wear it for several months, or for years, you won’t even notice the vibrations. You will actually feel a presence behind you—or the lack of it behind you. This is a very simple way of extending your senses. There are many more examples.

Teeth are another example. Instead of asking your dentist to implant gold teeth or different materials that can be really expensive, you could have a sensor, like a small microphone that allows you to hear ultrasounds and infrasounds, or any other little sensor that would allow you to extend your senses. There are many of these examples.

Are you considering anything at the moment, apart from your antennae?

Yeah, my teeth are something that I might actually use to move the antennae—maybe. I just thought about that yesterday. I have a lack of teeth now. I have a lot of space in my mouth. [Laughs] That’s why I eat a bit slow. It’s good because in that way I’ll have extra space. The next time I have another tooth removed I’ll have very big spaces on each side of my mouth. It would make sense to have it connected wirelessly to the mechanism that would move my antennae.

I’m still exploring how to do this through thought but I would have to wear a helmet because it’s still not well developed enough to detect thoughts. But if I want to do move my antennae now, I could do it through my teeth instead of with my thoughts.

Previously, we talked about the ethical and moral issues around cyborgism. Has this changed much in the last decade, or is it still a slow process?

At least people talk about it now. In 2004, there were no real conversations with people. It was: “Wow, that’s weird.” That was about the height of it. Whereas now, people ask more in‑depth questions. There is definitely a change in more of the philosophical and the ethical discussion. This is something that people are talking about much more, now.

Of course, your view of the future suggests that cybernetics will move into genetics. This will be a much more ethical and moral question for people. But you see that’s where things are moving, that’s how society is changing. In your mind, is this something that will happen sooner than people think?

Yes. It will be this century. Many children today will see this occur in their lifetime and might actually experience it themselves. In a way, cybernetics is just a transition, where we still need metallic body parts and metallic sensors. Whereas, eventually we will slowly stop using cybernetics and instead use our own DNA. For example, there are animals that can detect infrared. That DNA could be transposed to a human.

We can explore things like this—and also body parts. For example, using existing antennaes we could use DNA for the creation of my antennae and then biologically adapt it to humans by modifying my genes. As a result, the antennae would grow. Maybe it can be grown separately and then implanted. It would still be from my body.

There are interesting things going on in Perth [Australia], at the moment. They’re creating body parts from their own stem cells. They can grow parts separately…

If we refer to popular culture again, we might call what you’ve just described as superhuman—genetics being modified. But in fact, everything you discuss seems to refer back to the natural world. It’s back to biomimicry, where you’re suggesting if we look at what’s happening in nature and then mimic it through genetics for ourselves, it starts to remove the myth of the superhuman and brings it closer to the natural animal world. In fact, you, yourself, have said that you feel closer to animals now than ever before, possibly even closer than you do to humans.

Yeah. I’ve slowly felt less comfortable defining myself as a human, because if you call yourself human, you separate yourself from other animals and it feels wrong. With this thinking, you’re more comfortable defining yourself as an animal. But then, when you define yourself as an animal, you separate yourself from other living organisms. I feel much more comfortable defining myself as an organism.

I’ve slowly felt less comfortable defining myself as a human, because if you call yourself human, you separate yourself from other animals and it feels wrong.

In my case, I’m a cybernetic organism. Cyborg, because I have cybernetics inside me. When you call yourself an organism, or when you define yourself as one, your group is wider. You are at the same level as an insect or a tree. That’s how I feel. That’s why I also don’t eat animals. Since I was 12 or 13, I’ve never liked this disconnection from organisms.

The way we can learn from other organisms is by observing them and also learning from their senses. People don’t value the senses of other animals. They think of knowledge or intelligence or whatever. I think we should stop looking at the animals like this. We should start looking at their senses and how much we can learn from them.

In my mind, becoming a cyborg feels like it was a very deliberate design process for you: to observe, to find a solution which is deliberately designed, and then produce or reproduce it for a specific outcome. This is the design process. Is this something you think about, that you’re designing body parts? You’re designing a way to access senses? Or is it something less deliberate and more intuitive?

All my life I follow intuition—always! Everything has been…That’s the main thing which really…

Drives you?

Yeah. It’s just intuition. I don’t take thought too seriously. That’s the second thing.

That’s interesting. Can you expand on that?

If I think that I shouldn’t do something or shouldn’t go somewhere, but then I feel that I actually should go there, then that’s what counts. Even if I really think I shouldn’t do it.

So, the design is simply the way to achieve it? It’s not something that you deliberately set out to do initially?

No. For example, when discussing surgery for my antennae a doctor once said that this is not the zone where it should be done [pointing to his head]. They never do surgery here. They do it here, in the front of the face, where, for example, you can drill new ears, or if someone loses a nose you would drill the nose. If surgery is required it’s always here at the front, not at the back, not at the occipital bone.

They were trying to convince me to put my antennae somewhere else, for example have it sideways. And if you think about their reasons, they were—of course—quite logical. Maybe it’s true. Also, surgery in this area could be close to the spine and it could be dangerous. But my intuition was so strong. I knew where my antennae should be and I decided exactly where. Then they did it.

That’s one example of where, perhaps, if I had thought about it too seriously I might have said: “No, you better be safe.” That’s just one example.

Also, in 2004, when the sounds and the colours were overwhelming, I had lots and lots of headaches. I thought, maybe I should stop because it’s just too much. But then my intuition said that I shouldn’t stop, that I should continue and that the brain would adapt. And it did! That was also a moment where I didn’t do what I thought I should do. I did what I felt I should do. It’s constantly happening.

Your world is sound. I was wondering, is there a natural rhythm to the human‑made world or environment, which might be different to the natural environment? Is there a rhythm to what we’ve created as humans, and is there a rhythm to the natural world, or is it all very different?

Colour has no rhythm unless there’s…

Composition?

Yes! Or two colours at the same time. If there’s two colours at the same time, then they create rhythm—if they’re very close to each other. Human faces usually create rhythms, because we have different shades of orange. Usually the hair and the skin and the eyes for many people are three shades of orange, which is three shades of brown usually, or very close to each other. That creates rhythm when you play them together.

In nature, there’s also lots of similar rhythms, because in the forests you can hear many shades of green, which are many shades of the same hue. So that creates extreme vibrations, as well.

The reason I ask is that you did a project based on cities, seeking to identify the dominant sound of a city. Because of this, I was I wondering whether is there a rhythm to what humans build, because what we make is perhaps contrived, whereas the natural world is organic and has developed over millions of years. And there’s much more symmetry in nature. Does that translate to sound?

Maybe more into volume than it does to rhythm. Human‑created realities are usually louder than natural ones. It’s to do with saturation. There’s differences in saturation.

Finally, I’m going to have to ask. And I’m sure everyone asks you this, but what do I sound like? [Laughs]

[Getting closer with his antennae] You have high‑pitched eyes. G eyebrows. Your nose is between G and F#. Your lips are E. Your eyes are around C.

C, E, G. You have lots of different notes. E, C, G, F#—again F#, and then G, and F#. It’s F#. Five different notes.

Image Credits:

Neil Harbisson portrait photograph supplied by Neil Harbisson

Neil Harbisson, TED

Final interview portrait photograph supplied by Neil Harbisson