Legendary and influential American designer Milton Glaser discusses the circumstances which dictate the power and potency of dissent in democracy. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #4, which focused on the theme ‘Propaganda’. (Sadly, Milton passed away in 2020 on his 91st birthday.)

Note: This interview took place in 2007 and refers to specifics of that time.

Kevin Finn: With the proliferation of new media, is the poster, not to mention the poster of dissent, still a relevant medium today?

Milton Glaser: It depends what you mean by relevant. It is certainly not the major form of communication today. Designers love posters because of their physical size—that it’s close to a painting, rather than an 8.5″ x 11″ scrap of paper.

But if you are talking about posters being relevant in communicating to a large audience, certainly not. It’s relevant to the people who make it because it’s a way of expressing ideas to a small segment of the population, those involved in professional practice. It is a meaningful way of discovering things. In certain kinds of conditions, to certain kinds of audiences, for instance posters in the subway where a couple of million people might see it in the course of a day, it probably has some relevance. But it would be very hard to justify the poster as a major means of communicating, certainly in industrialized countries at this moment.

You once stated (in an interview with Macworld in 2001) “culture is defined as much by what is prohibited as by what is accepted.” The Internet prohibits nothing. How has this affected dissent today?

I think you need a really smart sociology professor to answer questions like that. But by and large what we know about the Internet today is hearsay because we have not attempted to quantify the information in any way. The dark side of democracy—the idea that everyone has become a source of information—is troubling because there is no vetting process to determine whether the information is coming from an idiot or someone with intelligence. This is problematic. I don’t think the consequences of this new adventure in communication is in any way understandable at this moment.

The dark side of democracy—the idea that everyone has become a source of information—is troubling because there is no vetting process to determine whether the information is coming from an idiot or someone with intelligence. This is problematic.

On a different note, after the tragedy of 9/11 there was a plethora of graphic reactions. Designers seemed compelled to respond to the event. But with the passing of time the general political awareness of the graphic design industry has waned somewhat. Do we need these horrendous acts to instigate political expression from the mainstream?

Well, it’s hard to tell. Again, these are not quantifiable questions unless someone has done a study to ascertain how much design activity there is relating to social causes at the moment, as compared to what they were five or ten years ago. When you ask those cosmic questions about the interpretation of what is going on, and all I have is anecdotal information, I don’t know how to respond.

I would say that there is a kind of current for social reform, concern about ecology and to some degree political activism within the design community. But how much is going on I couldn’t say.

I think 9/11 was a trauma for many people. I don’t actually think that, in terms of alerting the design community for the need to communicate about social issues, that it was very profound. It was an event that made people certainly feel upset about life as we now live it but I don’t think there was a direct correlation between that kind of response and a turning towards political activism.

When Ken Garland’s First Things First Manifesto (1964) was published and the subsequent FTF 2000 they both caused a stir at the time. But the intentions of those manifestos don’t seem to have been sustained in practical terms. Do you think there is a way we might ensure these themes to remain current?

I don’t know how we ensure anything in a changing culture. I think the only issue is how individuals respond and whether their sense of activity embraces social commentary. But that is unique to the design community. Modernism was, after all, a social movement as well as an aesthetic one. And so, there have been a lot of examples of concern for social issues in the history of graphic art but it sort of waxes and wanes. I would say that in the United States it has been less visible than it was in Europe, in terms of the activity of graphic designers.

However, I think now there has been a kind of an upswing and like all things—it’s sad but true—when they become trendy they become visible.

Modernism was, after all, a social movement as well as an aesthetic one.

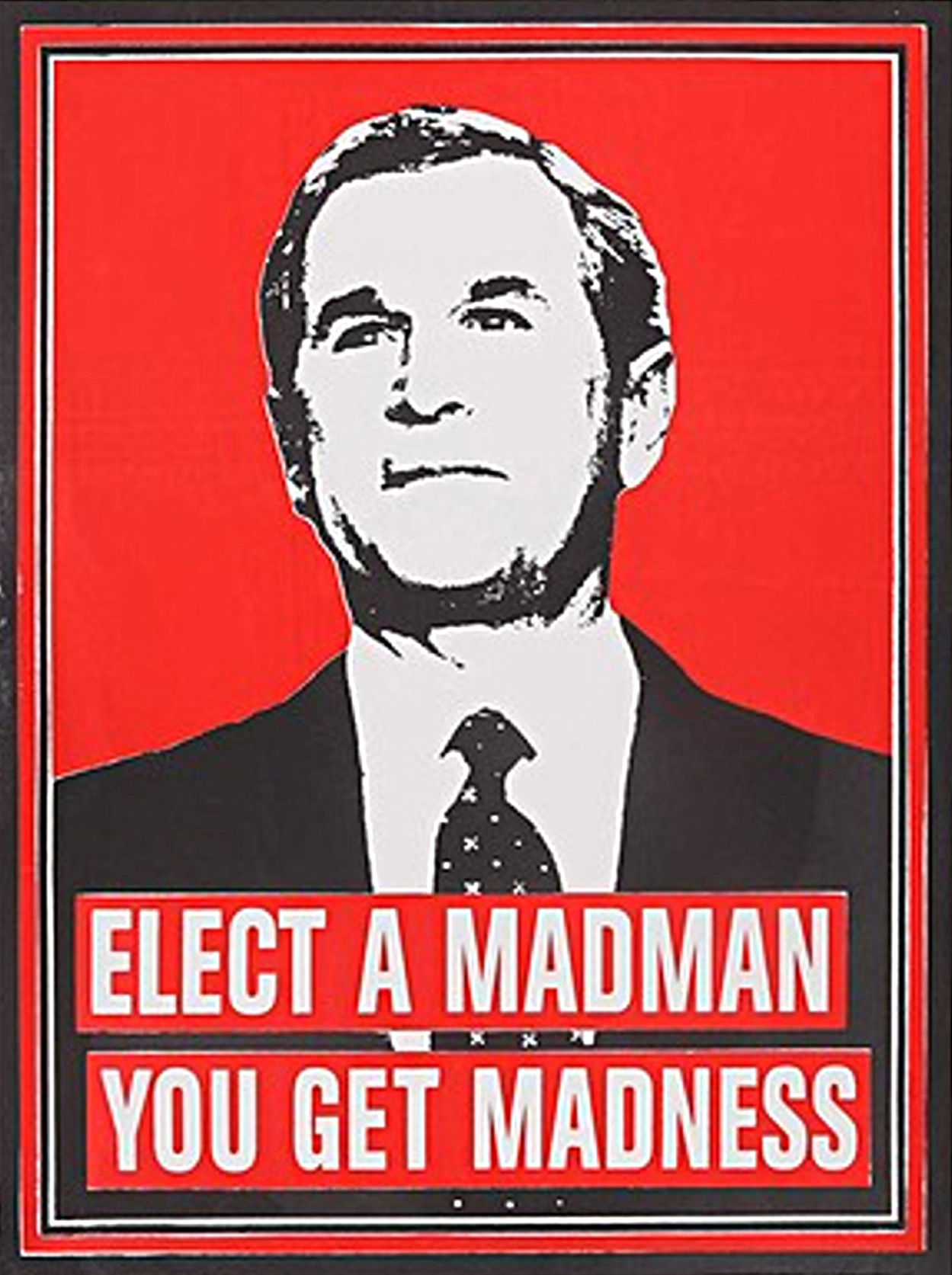

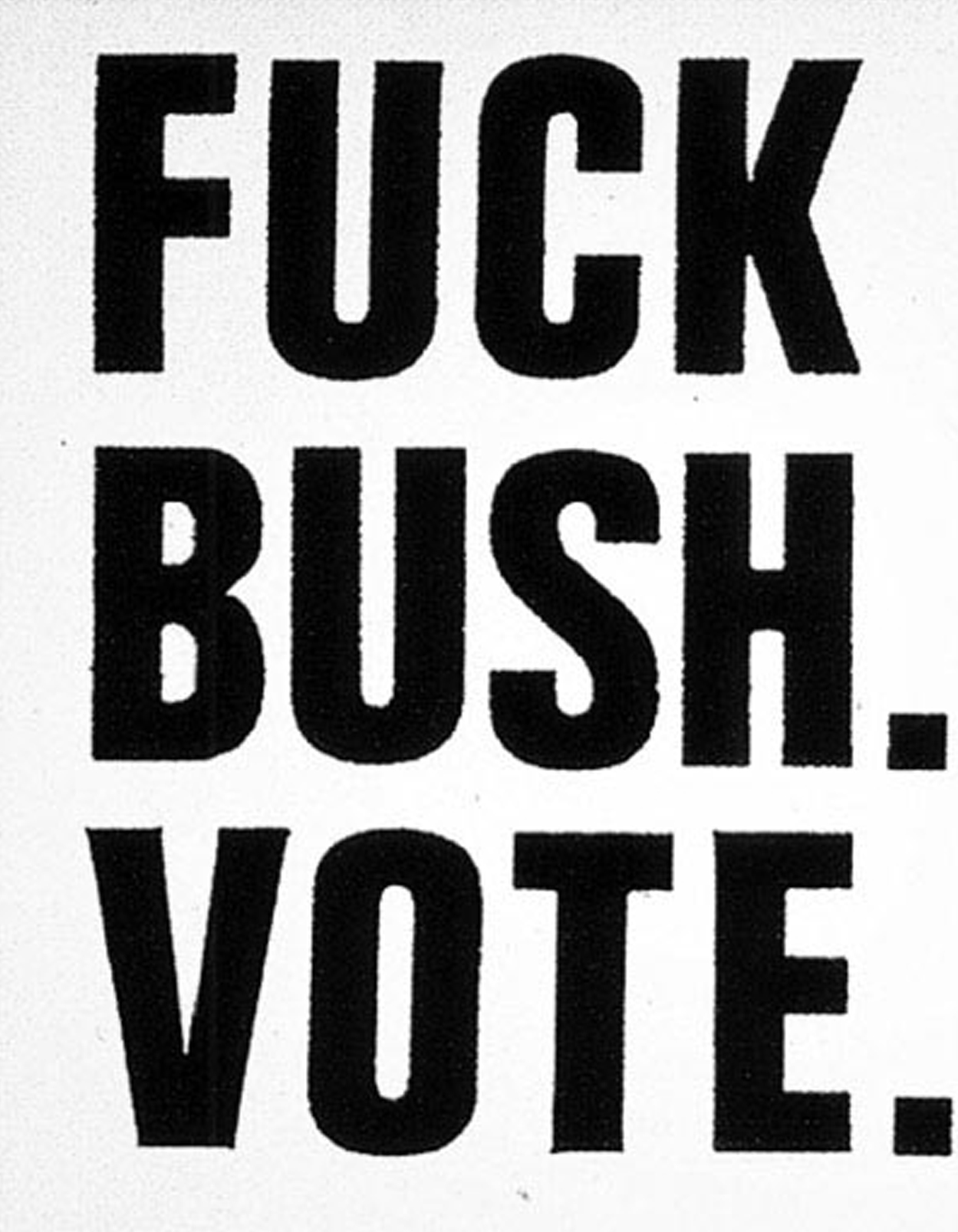

Yes, it seems at the moment, from what I have seen internationally but particularly around America, the policies of the [George W] Bush Administration have solicited a far more visible reaction than perhaps previous American administrations. Is this something you are seeing?

Well, that may be true. I did a book with Mirko Ilic called ‘The Design of Dissent’ [originally published in 2005], which has a lot of reactions to Bush and many people really hate him. The real question, which I always pose to designers and other people, is how you enter into the communication stream? I mean, how do you make yourself visible? What is the mechanism by which this stuff appears in the pubic? And as you know, that is a difficult part of the communication problem. I mean, you can go on the Internet and be one voice in a million, or you can put a poster up in your neighbourhood. But in the absence of mainstream connections and enormous amounts of money it is very difficult to make a position, particularly a marginal one, visible.

On the other side of this you mention in ‘Design of Dissent’, in your interview with Steven Heller that: “education trains you to be a conformist”. Does this point towards a type of graphic conditioning?

Well I don’t think it is unique to graphic design. I mean, all education basically instils a pattern of belief in people. Very often it is unexamined. But this is the nature of socialization in any culture so it’s not special to the graphic arts business and it is not peculiar to education. Education teaches you rules and, as you know, a good rule in life is to not accept anything, in the form of received information, without scepticism.

Broadly speaking—I guess we’re touching on the topic of citizen designer—what does it take to be a citizen designer and do you think the wider industry sees it as being important?

What is important is for individuals to feel, by virtue of their interests and their conscience, that they want to effect the life of their times. It also includes a sense of responsibility to the people you communicate with. It does become very personal on that level and can only become collective when you can link into other social systems. But as I said earlier, the difficult part is how you enter the culture.

You have (quite personally) entered into the wider culture with the ‘I (heart) NY’ logo. I know you have spoken in the past about how you included the words ‘More Than Ever’ after the 9/11 event, but I was amazed to hear that the response to this from the State was negative. Have they changed their view since then?

Well, the thing just passed because there was no impetus behind it to make it continue. There were no t-shirts, there was no promotional material, there was no budget, and after a year passed it no longer seemed relevant to continue to say ‘More Than Ever’.

The State resisted basically because they thought it was an infringement on their trademark, since they had trademarked the design I did—‘I (heart) NY’—and they thought that if I was making money on ‘I (heart) NY More Than Ever’, they should get a part of it. But since I didn’t make any money on it, it quickly became irrelevant.

In a similar vein, you have designed and produced a button [badge] stating ‘Dissent Protects Democracy’. How has that been received—generally?

Oh, I think it has been received well; it has been used, it’s been worn. I did that through, what you might call a Left Wing or progressive magazine called The Nation, which I admire and which has been at the forefront of good reporting about the war for a long time. They offered it to their membership, subscribers and people who read the magazine and they sold a lot of them so I presume they are getting good reactions.

But I think at the core of what I believe is that particular idea, which is: dissent is the only way you can guarantee a democratic society.

In terms of freedom of speech?

Exactly.

Contrary to that, would you say apathy is the enemy of dissent?

I would say that is one of the great problems in any democratic political form. When the people become apathetic and do not vote the possibility for a totalitarian impulse becomes greater. And that is what is happening in the U.S.

Getting a little more specific, there is a view that the majority of advertising is more about persuasion than information. No doubt our industry would be happy to believe that graphic design is the opposite to that particular view of advertising, but do you think this is actually the case for the most part?

No I don’t think it is the case. I mean, by and large we are very often in the persuasion business. Graphic designers like to make a distinction and very often there are distinctions. But very often we are in the same position as someone trying to persuade others to do things that are not necessarily in their own good. I’ve always had some trouble working in advertising, although I do some advertising every once in a while. But, by and large, I try to deflect that issue by not working for institutions that I believe can cause harm.

Would it be fair to say that dissent is a form of persuasion?

There is a great definition of art that I use, which is in fact a quote form second Century Roman wise man. He said: The purpose of art is to inform and delight. I like that idea of a definition very much. He does not say to ‘persuade’—but to ‘inform’. So I make a distinction between an act of informing and persuading, and I try to be on the side of the informing side of things.

Of course, corporations have co-opted counter culture. Does that make voices like Adbusters more, or less, relevant today?

I don’t know the answer to that. I mean everything successful gets cop-opted at some point. Anything that succeeds in our culture is copied so if you succeed by being anti-establishment you basically create, as Nike did, the illusion that by wearing their sneakers you’re against the establishment.

There is a thesis that ‘small distortions of the truth may not be recognised as lies’—but they are still accepted, nonetheless. How far do you think these distortions can go before they become propagandistic and are we less likely to see that transition?

You have to be careful about what you mean by these words; Propaganda is their belief, information is our belief. Propaganda means we don’t agree with the information. You could say that a healthy diet is propaganda, for example.

You have to be careful of what you believe to be the truth. Hold your beliefs lightly because the worst offenders in the area of truth are those who are most ideologically certain. After all, the entire Right Wing evangelical movement in the United States totally believes that it knows the truth. So I am very wary of anybody who ‘knows’ the truth, whether it is Left, Right or Centre [politically], because I think all truths are susceptible to distortion. Frequently, I don’t find it so easy to distinguish exactly between lies and truth and that causes a lot of mischief.

All truths are susceptible to distortion.

I guess depending on what side of the fence you’re on, certain actions can be portrayed as one thing or another—for example, insurgency or resistance? Which brings me to language, a huge part of messaging…

No question about that. I mean a suicide bomber is either a hero or a murderer depending on your vantage point, right? So once you realise that, you become a little more cautious about these general descriptions.

In your opinion, what make dissent ineffective?

I don’t know… [Pause] What makes it ineffective is confusion on the part of the maker and how they communicate the message. Sometimes dissent exists only in theory but in practice it has no effect.

Like everything else you have to choose the form of dissent that you want to employ. My argument with dissenting opinion is that it is often full of rage that is blind and inappropriate.

My argument with dissenting opinion is that it is often full of rage that is blind and inappropriate.

When I did a proposal against the Republican convention here [in the U.S] I felt the one thing that could not be shown was dissenting people being beaten up by cops and breaking picket lines and all that kind of stuff. This would create the absolute worse atmosphere for convincing people to oppose the Republicans, and so my proposal was to do a silent and solitary individual thing that demonstrated, through the use of light, that one should oppose Republican principles—I don’t want to get into it, it’s too long-winded and complicated, but all I am saying is that when you think about what effect your dissent might have, less anger might be more effective.

I’ll finish with this: I read your 12 questions in relation to ‘The Road To Hell” [included at the end of the interview for reference], which I thought were very interesting. Do you still employ these in your classroom and in your professional practice as well?

I do. It’s interesting, I just came off my teaching intensive a couple of weeks ago and I was surprised to discover (although it shouldn’t surprise me by now) that when I asked whether [a student] would work for a manufacturer who uses child labour, three quarters of the class said they would not. One quarter said they would.

When I asked the class if they would work on something that could possibly end in the death of the user, half the class said they would. And I thought, good God what in the world do these people have in their minds? How could they arrive at that distinction?

On one hand, it is sort of trendy to be against child labour even though it may be the only job for a child and the alternative is starvation. The fact that you would be perfectly willing to help kill somebody makes me very nervous, when you realise that people can invent any way to justify their behaviour, even when you are talking to bright, young, aware people who have a social concern.

People can invent any way to justify their behaviour…

Incidentally, how far down this road (to Hell) of questions have you gone, if at all, before you decided it was too far?

I would have to say that I have participated in about half of those things. I mean I have misrepresented movies and books and I have made packages look larger on the shelf. But also I haven’t been involved in at least half of the list.

Lastly, do you think the activity of dissent is currently in a healthy state?

Well, I think in the United States—if that is what you are referring to—there has been an increase in dissent. The President’s reputation has plunged. He’s down to 30% approval rating, which is phenomenally low and more and more people are speaking out.

I think dissent in the United States has been on the increase judging from what I read in the newspapers and what I read in the polls. Dissent in this case is directly related to Bush’s approval ratings over the last four years. And his ratings have gone down in a dramatic way.

Reference:

12 Steps on the Graphic Designer’s Road to Hell.

1. Designing a package to look bigger on the shelf.

2. Designing an ad for a slow, boring film to make it seem like a lighthearted comedy.

3. Designing a crest for a new vineyard to suggest that it has been in business for a long time.

4. Designing a jacket for a book whose sexual content you find personally repellent.

5. Designing a medal using steel from the World Trade Center to be sold as a profit-making souvenir of September 11.

6. Designing an advertising campaign for a company with a history of known discrimination in minority hiring.

7. Designing a package aimed at children for a cereal whose contents you know are low in nutritional value and high in sugar.

8. Designing a line of T-shirts for a manufacturer that employs child labor.

9. Designing a promotion for a diet product that you know doesn’t work.

10. Designing an ad for a political candidate whose policies you believe would be harmful to the general public.

11. Designing a brochure for an SUV that flips over frequently in emergency conditions and is known to have killed 150 people.

12. Designing an ad for a product whose frequent use could result in the user’s death.

Image Credits:

Milton Glaser portrait provided by Milton Glaser

‘Elect a Madman. You Get Madness’ poster by Kyle Gore, 2004

‘Fuck Bush. Vote’ poster by Tibor Kalman (year unknown)

‘I ‘heart’ NY More than ever’, by Milton Glaser

‘Dissent Protects Democracy’ badge, by Milton Glaser