Jessica Walsh—influential designer, founder of &Walsh, and business partner with Stefan Sagmeister [Sagmeister&Walsh]—talks about the importance of play, following your heart and the fallout from fame. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #8, which focused on the theme ‘Change’.

Note: This interview took place in 2015 and refers to specifics from that time.

Kevin Finn: Stefan [Sagmeister] once said: “Jessica is half my age, half my size and twice as smart.”

Jessica Walsh: Wow! You did your research. [Laughs]

How do you feel you’ve changed or influenced the business since you’ve become a partner?

What’s genuinely great about my relationship with Stefan is that we both really respect each others styles and ideas, but we have very different ways of looking at things. As he said, we’re two totally different people. I’m a small woman who’s half his age and he’s a very large Austrian man.

We come from very different places, so we see life in different ways and we bring that to the work we’re doing. That’s cool, because in some ways we have this similar style, but in other ways we don’t, which means we can push each other. If he has a really great idea, I might see things in a slightly different perspective and I’m then able to bring something to the table, and vice versa.

That’s more about the work. However, in terms of the business, do you think, now there are two of you—as opposed to just Stefan running the business—your influence on the business approach has changed things?

We’ve been doing much larger branding work since I’ve been involved. That started when I joined. I had a lot of experience doing photo shoots from the previous job I had worked at. He had this client Aishti and I started doing quite a bit of the art direction for the photo shoots.

That work brought us quite a bit of other work in that direction, and that evolved into doing larger re‑branding and advertising campaigns that also required TV commercials. The scope of what we do as a business has become larger since I’ve been involved.

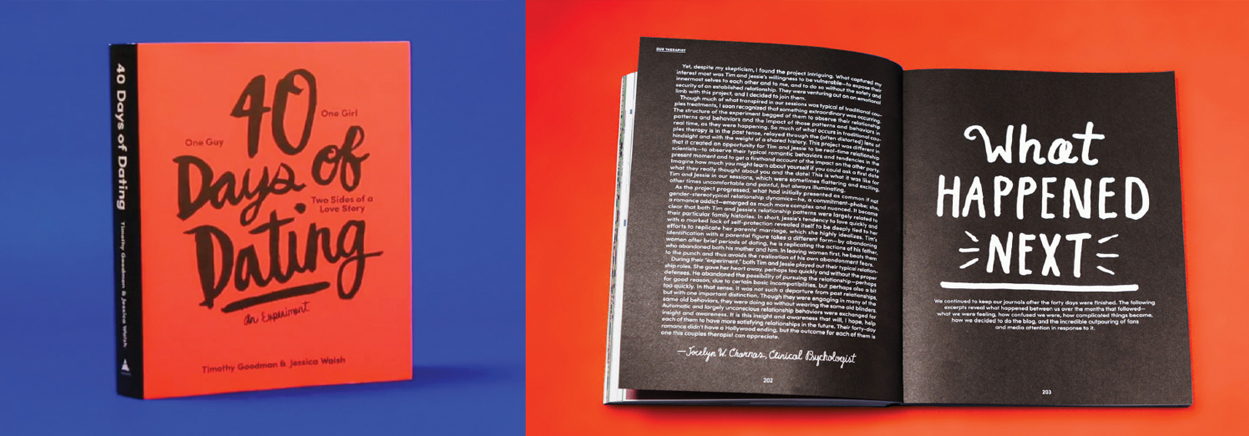

To switch things up a little, you’ve stated many times you highly recommend that people get naked. You’ve said that jokingly, but you’ve also used it as a very effective marketing tool when you became partner in the business. What interests me, though, is your project 40 Days of Dating. That was really being naked, because you exposed yourself in numerous ways: you became open with your doubts, your fears and being vulnerable. My question is: Should others consider a good business or personal strategy as being open and vulnerable?

Certainly… Both! I would say, for me, a large part of my desire and drive is because I grew up in a small town in Connecticut where I felt like it was very closed and everyone had a facade and was trying to make their lives seem so perfect.

For me, that was a very difficult environment to grow up in because of all these expectations, and I felt like people weren’t very genuine. That’s partly why I’ve had this desire to completely break out of that mold and be real and open.

Also with social media and everything, everyone is constantly curating their lives to seem so perfect, when it’s really not.

Everyone has ups and downs and everyone has shitty days. I don’t think it’s a very healthy thing as a society that we seem to be ignoring that, especially if you’re raising kids now, and if that’s what they’re seeing— these social feeds of perfect lives. That’s not how life is.

Everyone has ups and downs and everyone has shitty days. I don’t think it’s a very healthy thing as a society that we seem to be ignoring that, especially if you’re raising kids now, and if that’s what they’re seeing— these social feeds of perfect lives. That’s not how life is.

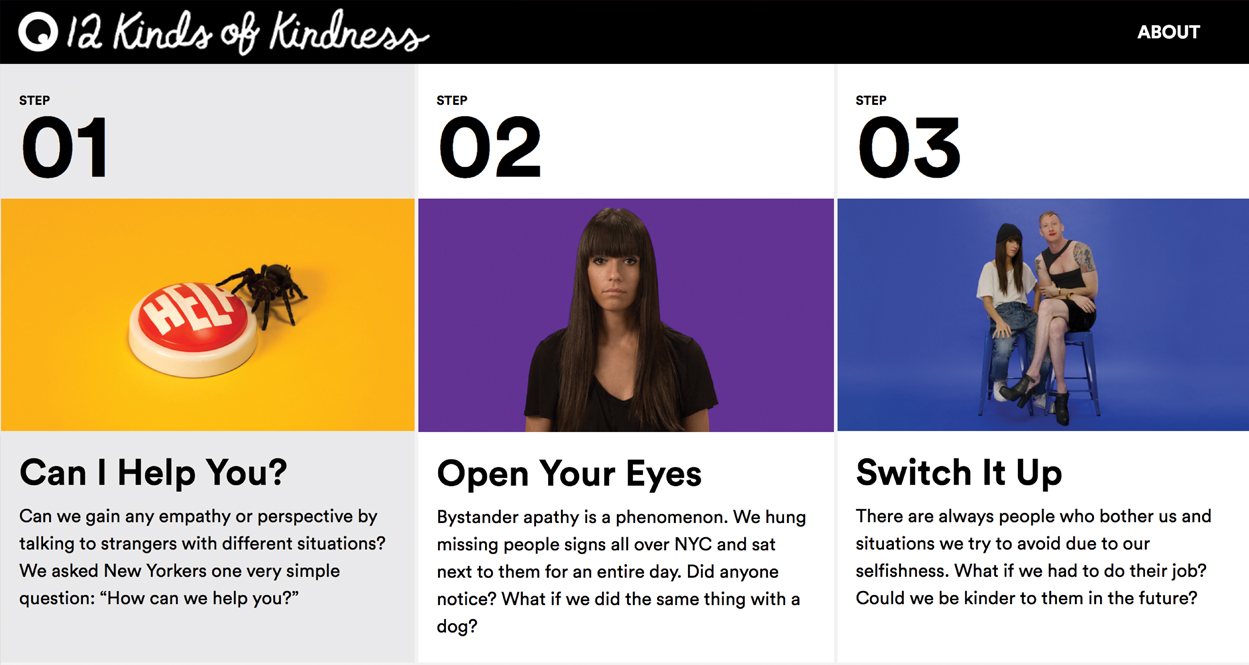

So that’s part of the reason that we wanted to take that leap and do 40 Days—to be real and open with it. That project is not even… There’s so much more. It’s given myself and Tim [Goodman] confidence to do bigger things. Right now we’re working on a project that’s also a social experiment, one that’s much larger in scope than 40 Days, and way more deep and real. [This project is called 12 kinds of Kindness and was launched after this interview took place.]

I want to discuss your personal initiatives because, when we spoke previously, you mentioned the amount of time involved on these projects is quite extensive. Does this put a strain on the business?

No. I’ve had… I don’t know what you would call it—creative block—a couple years ago, where I was really too overworked with all the client stuff. When I’m not happy with the work I’m doing, I don’t make good work. Even if I’m working 24/7 on client stuff, that doesn’t mean that I’m producing a lot. I find that when I mix it up and do these other projects, which keep me inspired and loving what I’m doing, this inspiration and passion feeds back into the client stuff.

It doesn’t take any time away because I’m actually faster, because I’m more into it and excited about what I’m doing.

I also know that when the wonderful Debbie Millman interviewed you and Tim she asked about the Warner Brothers 40 Days of Dating film proposal. At the time, you were really unsure about doing a film. In contrast, Tim was very sure about it and was really keen to pursue it. What changed your mind about going ahead with the film?

When the 40 Days blog blew up and went viral, perhaps one of the most exciting things that I got from it was that we really connected with people. We were getting emails from all kinds of people saying how the blog touched them in various ways, or inspired them to go to therapy. Or that it made them think about relationships differently. That’s so incredible, that we—as designers—have these tools where we can connect with people in a really efficient, fast and easy way.

It’s a pretty powerful thing, and it clicked something in me that was pretty amazing. At first I was, like: “Oh no, a movie! They could turn my life into anything.” Then I realized that a movie would simply be advertising for the project, and drive more people to read the book and to read the blog, and in a way would give us a bigger audience for the future projects that we had.

40 Days of Dating, and the reasoning behind it, was a social experiment, which developed into a highly successful blog and then to a very successful book and now into a film… Do you think designers are truly in a position to influence or change culture?

That’s a very big statement. Certainly ideas, and good messages, can change culture. And design is one of many tools you can use to get those messages out.

The reason I ask is there’s a lot of chatter around at the moment in design circles about how designers can change culture, that designers can change the world…

I’ve always been wary of that whole “Design can change the world” thing, because I don’t think design can change the world. People can change the world—and good ideas.

Graphic design, like filmmaking or documentaries or any of these things, are simply communication tools to get those ideas out there. Yes, it’s a very valuable, awesome tool but I don’t believe graphic design is going to change the world. But the ideas can…

I’ve always been wary of that whole “Design can change the world” thing, because I don’t think design can change the world. People can change the world—and good ideas.

Many might say that you became famous almost overnight. Once you became a partner with Stefan, that really jettisoned your profile in a much more high profile way. Has this changed you in any way? For lack of a better way of saying it, how are you dealing with being famous, all of a sudden?

When it first happened, I have to say, it was quite overwhelming because I felt like all of a sudden people expected something of me, and that now people were watching me and that I had to be constantly delivering a certain level of work, or that people would critique me. I got really caught up in it for a moment. There was maybe six months after the partnership first happened where I was quite depressed from it all. Then I realized how silly it was. The only expectations are what I put on myself.

At the end of day, all I can do is to do the best work I can that makes me happy and that drives me and keeps me excited and motivated about life. Some people are going to like it and some people are going to hate it, and that’s life. I can’t worry about everyone in the world liking it.

That’s how it was when I was growing up. I was always trying to please people. In a way this realization was good for me personally, because I was, like: “I have to get over this. Some people are going to hate me. That’s fine.”

[Laughs] Of course, it also now puts you in a position to influence certain things, because of your high profile.

It has a lot of benefits, this high profile. It allows us more work so we can be choosier with the work that we take on. When we can be choosy, we can do better work—and that only leads to doing better work.

It also means if there’s something I believe in, or an artist I really like that I want to promote, I have a huge network now that I can do that. It’s really nice. [Laughs]

You mentioned previously your role is quite varied and that the role of a designer is changing rapidly. That said, some designers would subscribe to being a generalist whereas others subscribe to being a specialist. Do you have a view on either of those?

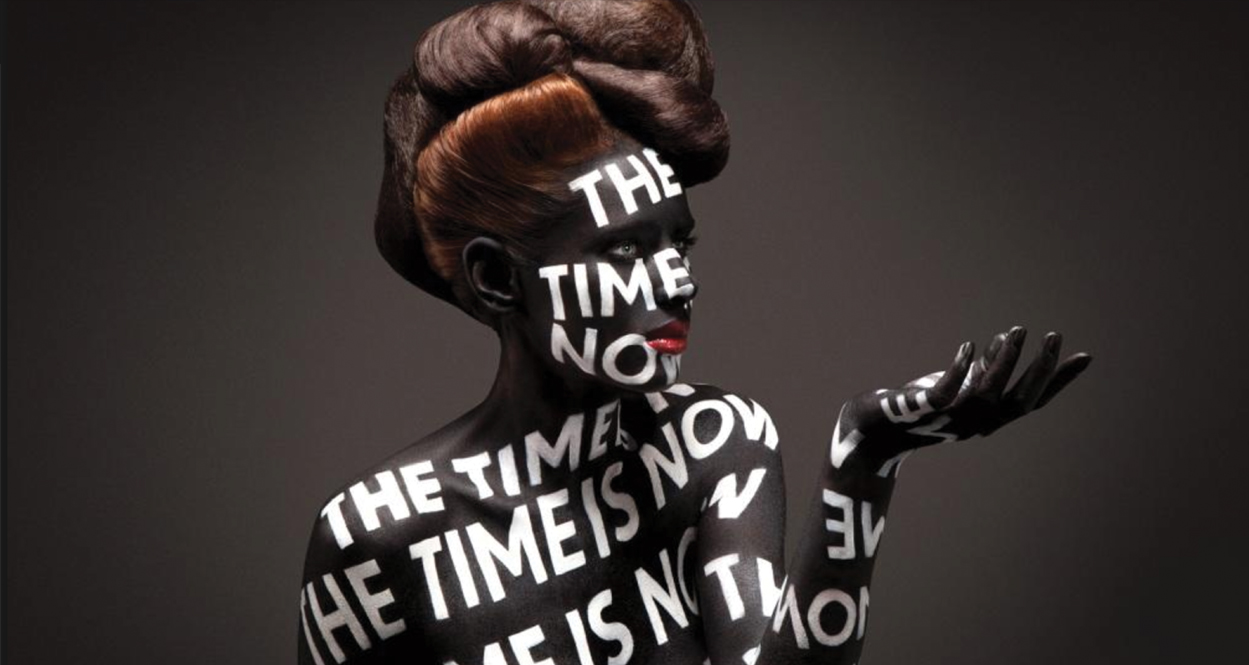

You have to be one or the other and not in the middle. I find that people are very successful when they are super specialized in something, even sometimes very random. For example, I have a person that does body painting for my projects. That’s all she does—body painting! And she gets tons of work, because it’s so specialized and there are so few people in the world that do that.

If you’re an absolutely incredible film colorist, and that’s all you do, you’re going to do well—if you’re really good at your job. But I don’t think you can now just be a graphic designer. You have to be able to work across—or at least think across—a few different mediums.

You describe yourself as being a: graphic designer, art director, illustrator, copywriter, strategist, project manager, and animator, among other things. But would you describe yourself as an artist?

It’s funny, because a lot of people call me an artist and I’ve always been really hesitant. It somehow seems like if I call myself an artist, that’s somehow pretentious. I don’t know why I feel that way. It’s in my own head. It somehow seems like a level above what I am…

[Both laughing]

Previously, I’ve asked Stefan the same question—about whether he sees himself as an artist—and his response was a resounding “No!” But when I asked Ji Lee if he thought Stefan was an artist his response was: “He’s absolutely an artist.”

For me the difference between an artist and a designer is that design has a function, and art doesn’t need to. Art can be purely form. I do believe that most of the work that I do functions somehow. Even if it is not for a client, it still is wrapped around some message or idea I want to get across. In that way, I do think I am a designer.

One of your beliefs is: “Don’t expect people to change.” Why do you subscribe to that view?

That came from earlier relationships I’ve had, where I thought I could change people—and that the relationship could work, as well. Little things like: I’ll get him to do the dishes, you know? These flaws which everyone has. But I realized that people don’t really change that much, and if they do it’s on their own terms and over time. You can’t go into any relationship, whether it’s romantic or a friendship or a business partnership, thinking that you’re going to be able to change them. You have to accept people for who they are, and let them grow as they grow.

Of course the other side of that equation is changing people’s views on things. For example, you talk a lot about some of your clients who, when you’re presenting work and their response is: “I don’t know. Should we have that [component] in there?” But your response is often: “Absolutely. Trust me. It’s going to be awesome.” Is trust a big part of the work you do with your clients, and how do you instil trust?

It’s a big part of how we choose our clients. We like to work with clients who really love the work that we’ve done in the past and are looking for that mentality we bring. We like to work with clients who we think are open‑minded and flexible to new ideas. If that’s the case, then it’s usually pretty smooth from there. Of course we’re not mind readers, and sometimes a client surprises us and turns out being not quite as open or flexible as we initially thought they were. Then it’s more of a push or a struggle.

But I also find that fascinating. I think, if I wasn’t a designer I would’ve gone into psychology. Especially when you’re running a design studio, a lot of it is client management, and a lot of that is psychology.

I realized that people don’t really change that much, and if they do it’s on their own terms and over time.

Do you have systems in place to navigate those sorts of conversations, when a client might not turn out to be the way you would hope? Do you have a mechanism in place where you say: “We will withdraw from that client,” or “We will only see it through to a certain point”?

It’s completely based on the situation. There have been projects, which we’ve moved on from. For example, one client didn’t like what we did; they wanted something that was totally different, something that wasn’t us, and we didn’t feel like we would do a good job for them. We’re not really interested in this type of situation. We have enough work coming our way that we don’t really need to do work just for the money. When we take on a job, we want to do stuff that’s going to benefit our clients. If we feel like we’re not the right people for the job, then we’re not going to do it.

I think, if I wasn’t a designer I would’ve gone into psychology. Especially when you’re running a design studio, a lot of it is client management, and a lot of that is psychology.

Many would say: “Jess, Stefan. You guys are in a really privileged position to be able to do that.”

We are.

To counter that, I remember somebody saying the same thing about Vince Frost. Their view was: “But Vince, it’s easy for you. You get all the good briefs.” But his response was: “No, I get the same briefs everybody else does. It’s what people do with a brief that counts.” Would you subscribe to that view?

I don’t think that’s true. When you get to a level where you’re more well known, you do get more briefs coming your way and you can be choosier. I do think there’s an element to it where, as he said: “It’s what you do with it.” Of course. Over time, as you do more and more of the work that you feel represents you and your studio, you get more and more opportunities.

Do you get a lot of people requesting similar work you’ve done for a previous client? I guess, it’s part of choosing a client, but is there a mechanism you have in place to help avoid requests to do similar work?

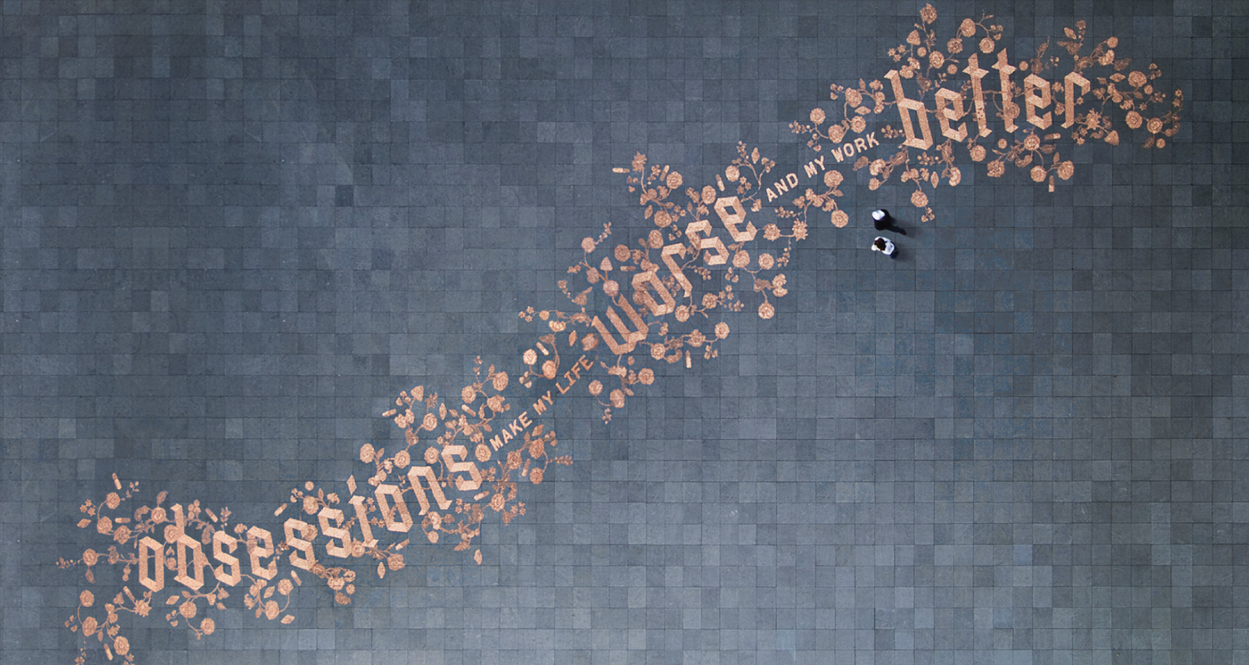

Luckily, the reason a lot of clients come to us now—or a large part of it, at least—is the conceptual side. They don’t really know what they’re looking for and they want us to answer that, because we have become a bit known for doing that, which is great. Occasionally we do get people that say: “I love that type installation you did, and I want the same type out of coins but for this brand.” That’s not really interesting to us. It’s much more interesting to us if we can evolve how we’re working and create things that are new.

My personal belief is that a designer’s greatest skill is being able to make decisions. In some ways, you seem to help the decision process by creating rules in certain situations. Are those rules arbitrary? For example, with the EDP identity project, you deliberately decided to use only four shapes. Is that driven by specific thinking related to the project, or is it arbitrary—or do you it mix it up?

Some of them are arbitrary, but most of them I would say are based on the content. At our studio, when a client comes to us we spend quite a while purely on the research phase of who they are, meeting them, learning about their history; and really understanding the content we’re designing for. Often times, those restrictions come out of learning these things.

For example, EDP was probably one of the more random ones. We knew we wanted to create some ‘morphing ball of energy’ because that’s the core of what they do. We were struggling formally about how we might get there, so that ‘shape to trait’ was somewhat random, but it allowed us to get to where we wanted.

We tried it out and it was working and so we deliberately decided to stick with it and see where it went. It was a big evolution. We started with the logo, but then we asked: “Can we make illustrations like that?” “Can we animate those illustrations?” And that’s how it evolved into the TV commercial.

To finish, and this might sound like a strange question but, with so much attention on you how do you deal with doubt?

I would say that I’ve become much better over the years at trusting my instincts. When I do have doubts it’s usually when I’m doing something very new, something that I haven’t done before, like this new personal project [12 Kinds of Kindness]. It’s so much further from anything I’ve done, and that really scares me, but at the same time I know that scary feeling is usually a good sign. It means you’re doing something worth doing.

I would say that I’ve become much better over the years at trusting my instincts. When I do have doubts it’s usually when I’m doing something very new, something that I haven’t done before.

This whole fame thing is funny to me, because I don’t think you can get fame by trying to get fame. You have to be honestly good at your craft, or whatever it is you do. Then that [recognition] follows. I don’t know anyone that’s like: “I’m going to be famous!” Or: “I’m going to be rich!” Or: “I’m going to fall in love!” I don’t think you can chase these things. They come naturally through honestly living and doing.

Image Credits:

All images provided by Sagmeister & Walsh