Daan Roosegaarde—Dutch innovator, founder of Studio Roosegaarde, and Young Global Leader at the World Economic Forum—talks about his passion for prototyping the future of cities and what it means to be a leader in society and design. This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #8, which focused on the theme ‘Change’.

Kevin Finn: Among other things, your work involves art, design, innovation, science, engineering, architecture, business, and politics. So, how do you describe yourself? How do you describe what you do?

Daan Roosegaarde: I’m a maker [laughs]. It’s very simple. And most of all, I’m a hunter. I hunt ideas, which is very important. I have an idea in my brain and I become a sort of a solitary prisoner of the imagination. I start hunting the ideas to grab them, to drag them into reality. That’s the best way to describe it.

All the things that you mentioned are somehow tools in order to enable that. I’m in the studio with smart people, so you need an entrepreneurial side, you need to work inside the artist to make sure an idea survives in the world we live in. And you need a sort of political agenda to create impact. But I think, most of all, it’s the hunting and the capturing of an idea, and then dragging that idea into a better direction.

In 2006, you founded Studio Roosegaarde and since then you’ve made a massive impact, not only in creative terms but also on a social and cultural level, too. How did you embark on this trajectory? What was your foundation project, or your initial sponsor, or client?

I started when I was studying Fine Art in 2003. I built one of the first liquid space installations. It was a huge sculpture—eight by four by five meters. I made it with some whizz kids from the The Fine Arts Academy, which was based nearby.

When you entered the space it would become smaller and bigger, with the notion of space reacting to your senses, rather than the sum of walls, door and windows.

We worked on that project for about a year, to a year and a half. When it was launched, it worked for three weeks, and then it died. But that was the first time I realized that I can use technology to bring things alive, where the visitor isn’t just an observer but a participant—sort of directly connected to the DNA or the behavior of the artwork itself.

Jumping out of art school I studied a Masters of Architecture, and then worked at [Rem Koolhaas’s] OMA, as well as MVRDV, and some other architectural studios. Around this time, we built the first Dune project, which uses fibers of light that react to the sounds and motion of people. We actually did the first pilot in the Maastunnel, the pedestrian tunnel, in Rotterdam.

And then the Tate Modern called to do a piece with Lucy Bullivant for a big show in 2007, called 4D Social, which was sort of important because I think that was actually the first time we got a little bit of budget. We had budget for six months to make the piece for the show.

That’s when I got the studio space with the people I worked with—whom I had paid in ‘pizzas’ before—and was able to give them a little budget. But we soon realized we would only be up and running for six months and then we’d be broke again, so something had to happen. That’s how the studio started.

You said that if you didn’t get another project in two or three months from that time, you’d be broke. But if we move onto today, you’re now a Young Global Leader at the World Economic Forum. How did that come about and what’s your role there?

Well, I’ve always kept investing in new ideas and new projects. I’ve always had—how do you say it—a good atmosphere of being surrounded by a good team of people who can pick up things and handle them. Although the team has changed, the people with whom I started with have all left, but there are new people around me now. And that’s very important.

I think it was also a time—and it still is a time—when we started to connect this sort of high technology with more social interaction. It was kind of a ‘human and the machine’ type of research. And we achieved it; we created our own little niche, I think, even with that first museum installation.

Now we’re attracting larger landscape type projects; we just got the go-ahead for a project involving a 32 kilometer dike in The Netherlands. That’s going to consume the coming five years of our time, which is great.

But it has always been about changing the dream, materializing it, and also feeling the zeitgeist—plugging into it and questioning it. We ask questions like: Why are we shutting down street lights at night? Do we accept pollution? How does a jellyfish emit light underwater without battery or solar panel or an energy bill? We’re constantly asking what can we learn from questions like that. It starts with asking questions, and then dragging them into a proposal.

But the impact has grown, and that’s also because I refuse to be put in the white cube of a museum, where signs read: “Do not touch.” I’ve always gone outside to public space.

It has always been about changing the dream, materializing it, and also feeling the zeitgeist—plugging into it and questioning it.

If we consider the perceptions around the World Economic Forum, we understandably think ‘business and economics.’ Do you think that a designer’s role, in the position that you have, is purely to question, or is there another aspect to that role?

No. More than ever there’s a desire for new ideas. You can feel that the big corporations, big CEOs—even the ones that have a lot of money—have very few innovative ideas, have very few ideas about the future. This is the role of the designer, or the maker, or the artist. To come up with new ideas, to build them, to work together, and to materialize.

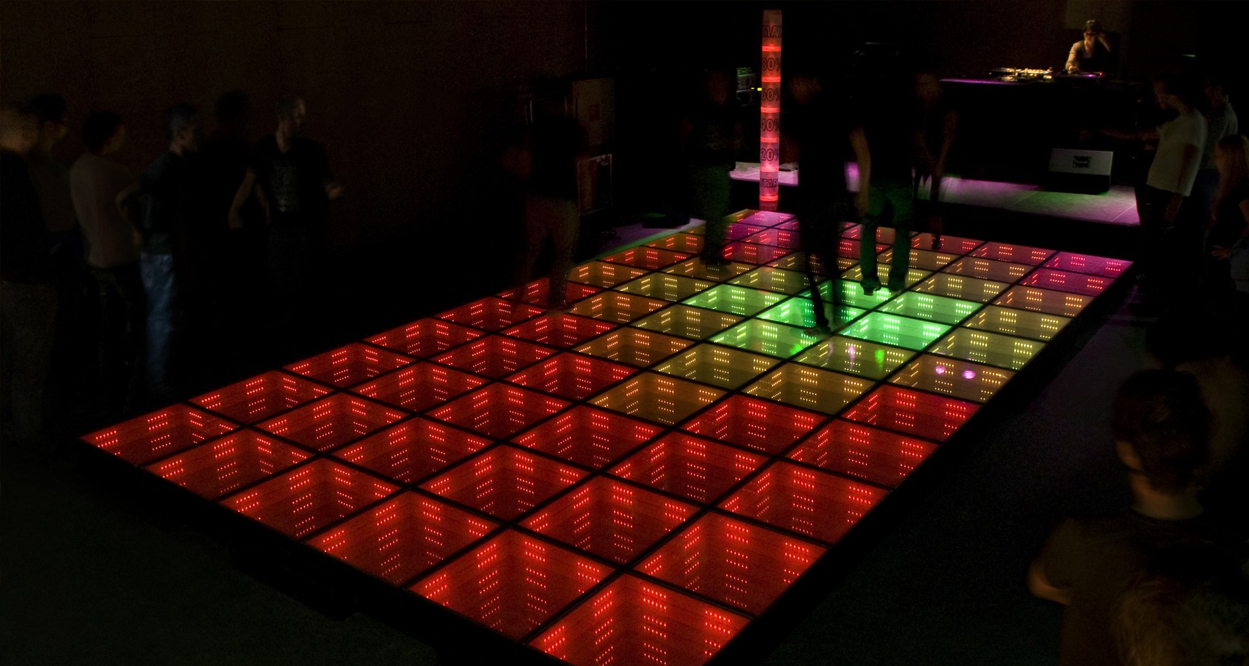

In a way, when we did Sustainable Dance Floor in 2008—harvesting energy from dancing—this was the first time we actually connected design and art with social topics, like energy. Then with Smart Highway, we connected this to mobility, and with the Smog Free Project, we connected it to health.

There is a real desire for creative thinking and creative leadership in this hard capital world, because the old system isn’t working anymore. Money is not the most important thing out there anymore, and it’s crashing. It’s crashing! It’s not working, so we need to reinvent, to prototype a new world, and to build it. I think that is the role of creativity.

We’re discussing how business is changing. And based on what you’ve just said, there’s a real desire for creative ideas. But do you think there’s anything within the design disciplines that needs to change?

I think that, for too long, design has been focused on making another chair, another lamp, another table. With all due respect to my fellow colleagues, we have enough. We have enough of that. Please stop. Stop making them, and designing them.

There are so many problems and potential niches out there which need this creative thinking. You just need to go there and own it, and say: “Hey, I’m an expert in this. I have ideas about this. Look at me trying to make sense of it.”

What I notice when I’m at Salone del Mobile in Milan, and events like that, is a lack of curiosity towards the future. I think this is limiting our creative freedom.

I think that, for too long, design has been focused on making another chair, another lamp, another table… we have enough. We have enough of that. Please stop. Stop making them, and designing them.

It’s interesting to suggest “we have enough”. It strikes me that every developed and developing economy pushes for economic growth. But this insatiable desire—often fueled by political agendas, it must be said—is unsustainable, given our current global issues. Do you foresee a future where constant growth is not a requirement, and might even be frowned upon?

Yeah, but then you have to define what growth is in that way, because the future will not be linear but exponential. That’s the difference. For example, let’s focus on mobility. If you focus on underground parking places, you can spend all the time, money, and innovation to make the best parking place in the world. It’s clean, and it’s spacious, and everybody knows where to go—blah, blah, blah! And you can spend all your money in the world on it. That’s great! But then the self-driving car comes along and you suddenly become obsolete, or less important, because the car is self-driving. Why does it need an underground parking place?

What I’m trying to say is, things which can be meaningful now, and in which you can invest, which you can grow, might become obsolete because of new technology, because of new ambitions that people have. I think growth should be mostly focused on redefining what is necessary.

What is the true answer? I’m not sure yet. In many ways, it’s easy for me: being Dutch, having a Dutch passport, and being able to travel. But when you live in China or India, there is a short term vision due to circumstances. But there must be a way.

Taking into consideration where we live and our circumstances, if we look at what’s been happening with the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe, once again it illustrates the impact of an abrupt movement of people across borders as they flee their frightening circumstances…

And we have no idea how to deal with it.

Exactly!

All these politicians have no idea how to position the mass of people. Some share their houses with refugees. It’s all great, but is that solving the problem? No, it’s just trying to show a sign of empathy.

Of course we’re likely to witness another increasingly worrying kind of refugee—the environmental refugee. Do you think there is—or are you aware of—any sort of programs that might be put in place? Are there any discussions at the World Economic Forum around how countries might react to the economic and societal impact of this seemingly inevitable environmental refugee crisis?

Oh, Absolutely! Actually, last time in Davos [where World Economic Forum meetings are held] there was an installation of refugees being filmed, and trying to give them a human face as an art installation, so it’s definitely a topic there.

I believe there should be a new international human right, the right of Schoonheid (a Dutch word that literally means beauty that cannot be properly translated to an English word); that everybody has the right to clean air and water. It’s like, the moment you are born on planet Earth you have these rights, and governments and people around you should take that into consideration and should validate that human right. I think it starts there. Huge groups of people are denied that right—even now—and that’s problematic.

Of course, in your own country there was a group who took the Dutch government to court and successfully sued them in relation to an environmental case.

Yeah. So you see, there’s a whole system of economy, and growth, and progress, and it’s hitting us in the face, and we don’t know how to deal with it. So, there are two possibilities. Either, A: the current system adapts and changes; or B: it breaks down into 5,000 little pieces and something new has to come out of that, and we see where it takes us.

When we spoke in India, we briefly discussed a recent World Economic Forum panel, which included Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever. The panel focused on the role of business and climate change. All four members of the panel agreed that business needs to—and is willing to—play a bigger role in reversing, or stemming, climate change. However, even though they were optimistic, they acknowledged the prediction of a devastating 4 percent increase in temperature, which may only be reduced to 3.5 percent, but it actually needs to be capped at 2 percent. How do you remain optimistic in these circumstances?

[Laughs] I believe we have a duty to be optimistic towards ourselves, towards others. I don’t have an answer for that. Sorry, I don’t have the obligation. As a maker, the only thing I can do is use all the creativity and energy that I have to come up with new proposals, new ideas, how I want the future to look like and to engage and enable people to create a movement.

For example, when the Kickstarter campaign we launched for the Smog Free Tower finished over 1,600 people supported it, engaged with it, shared it, and said: “Yeah, why do we accept pollution? Why do we accept this as something normal?” These are just strong movements, which are created to give a different voice to the discussion. But in the end it’s about leadership, and about people in charge making the right decisions. It’s my job to feed them with options that they might not have thought about. That’s what I can do—and the rest is the rest.

[Laughs] It’s interesting that you bring up the Smog Free Project, because I read that you were in Beijing and could see from your hotel window the iconic headquarters of the China Central Television, known as the CCTV Building. But then later that week, the now famous Beijing smog had all but obscured the building. I believe it was at that moment, when you couldn’t see the building, that you decided to tackle smog, which is a huge, huge issue. Is this how you often decide on pursuing a project, through observation?

Oh, Absolutely, because it was such a sad image, because I realized, A: “I cannot see the world anymore, so I’m just trapped.” And, B: “I know the impact of smog on human life. We live two or three years shorter.”

There was a big article which mentioned three million people per year die because of air pollution. It’s more than AIDS and malaria put together! It’s like: “Are you insane? Who decided to do that?” So, as a studio, we vote on what projects we want to tackle—and we agreed to tackle this.

It starts with a personal sadness, or a personal frustration, or a personal interest, and from that I try to shift it, to change it, to reconnect things, with hope—not just as a symbol, but to really engage a different discussion.

This is the first chapter of the book “the solution”. [Laughs.] This is what I’m good at. This is my way of observing our world and our reality.

When referencing the Smog Free Project, which is the world’s largest smog vacuum cleaner, you’ve stated: “It’s not going to cure smog on a large scale, but at least we can remind people what clean air looks like.” You’ve been meeting with Beijing officials to discuss your ideas around this project and your objectives for reducing smog. Can you elaborate on the Smog Free Project, but also what Beijing’s response to it has been?

I think the Beijing government realizes more than ever this issue of air pollution. They declared a war on smog four or five years ago. Most of the measurements they’re taking—and the actions they’re taking—are countering it, including relocating factories to less inhabited areas and encouraging people to cycle, in a world where the car is a status symbol.

I think we should do more, not less. But it’s China. In the beginning, when you present your ideas, they don’t know you. They haven’t seen you before, so they have to get used to you.

We had some fruitful discussions. And there is incentive to change— because of the smog free tower actually being there. Our Dutch Ministry of Health System has also validated our tests and approved it, so there are official documents which can be shared with the Chinese government. That helps them, especially with the 2022 Olympics. They really need to catch on and fix this.

There’s a lot of sentiment in the beginning. But Beijing, and other cities, wouldn’t directly support the project initially, because they were of the mind: “Yeah, but then everybody knows we are a dirty city,” and I’m like: “Yeah, but, A: everybody knows already. You can see it,” and, B: “so what are you going to do? You can’t do nothing. So what’s the answer?”

Within a political system in every country, there’s a risk-avoidance mechanism which pops up and kills innovation. So you need to have laboratories, areas in the city where you can test, where you can experiment, where you can learn, where you can fail, where you can update.

The Netherlands is defining this as Creative Industry, realizing you have to spend money, time, and energy on it to help it mature. I would recommend that every city is more open towards these kinds of new ideas and innovation. It just gives them a chance. Maybe four out of 10 will fail. But you still have six really good new ones. That’s also part of innovation.

You’ve mentioned the political situation in China—among other things the need for clean air for the 2022 Olympics—along with global awareness about the Beijing smog, which doesn’t help China. Is this how you navigate the political landscape, using context, or is it more about metrics, measurements and documents like the Dutch Ministry of Health has provided? Or is it about both?

In a complex world, I think you need both strategies. It’s the same when you’re in the shower and you want more warm water. To get more warm water, you can add more hot water or you can have less cold water.

There are always different ways to achieve your goal. In this case, you need to put forward new goals. On the one hand, you need to address the social agenda, like: A: “Hey, be good for people. Be good for citizens,” and, B: You need to prove it, to show it’s possible—and in a language they understand, particularly when we speak different languages.

I remember at the beginning of the Smart Highway a few years ago, when we were working with a high profile multi-infrastructure company. We didn’t know each other that well, and the directors were showing me around.

While walking around the corridors I mentioned that the curator from the Tate Modern was coming to our studio the following week and that I was very excited about it. Modern; good museum; London! They sort of looked at me in a complete shock, and I’m like: “Are you jealous? What’s going on?”

It actually took us a couple of hours to realize that the word curator in my world is, of course, a moderator, someone who makes an exhibition. But in the infrastructure business world, the word curator means the person who knocks on your door when your company goes bankrupt. [Laughs] That’s a curator. When you go broke, they come and do all the costs, and check what you have in stock, and stuff like that.

They were like: “My god, this guy’s going bankrupt, and he’s actually enjoying it!” We were both Dutch, so if we already had this misunderstanding about one word, then you can imagine doing a several million Euro Research & Development trajectory crunching business, where there isn’t a 100 percent guarantee, and you need to fight for it. When you do something new, you need to speak several languages to achieve your goal. Absolutely!

I guess the other side of it—and lets take the Smog Free Project again—is about capturing the public’s imagination. And that’s a powerful tool…

Absolutely.

The way you achieved this is to suggest they can create a place that’s 75 percent cleaner than the rest of the city. This creates a powerful incentive for people to clean the whole city. But you’re not just stopping there.

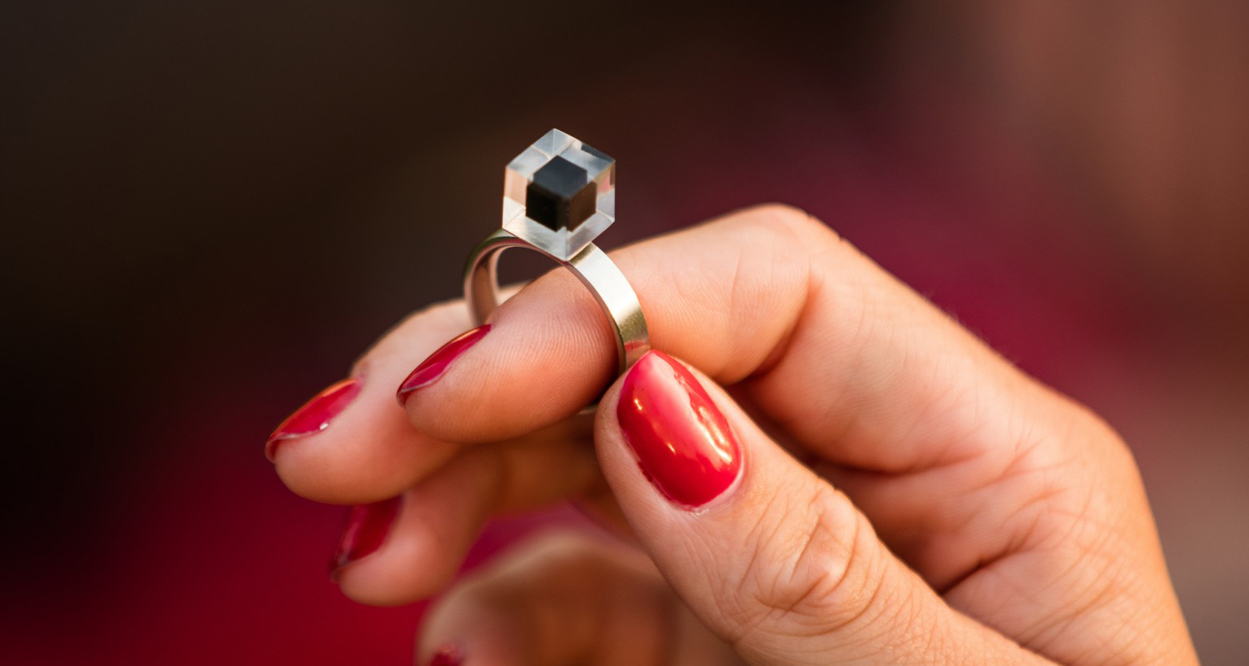

You have created jewelry—the Smog Free Ring and the Smog Free Cuff Link—which fuses compressed smog particles. That, in itself, captured the public’s imagination. Is that a tool that you actively seek to use?

Yes. You have technological innovation—the tower—which is a machine which does its thing. And, of course, it’s tested and proven. But you also need social innovation to make sure that it changes perceptions. Because if it’s just technological innovation people will just rely on that technology, but no real change is made.

[Laughs] But you also need social innovation, something that becomes a part of their emotional values, part of their lifestyle. You need it to infiltrate in that way. The rings and jewelry are a great way to achieve this, but also to just get initial funding.

The concept is very simple: use the waste as fund raising for the actual Smog Free Tower. The first time I explained this to my business developer she was, like: “What are you talking about?” It was like a silent car alarm for her.

[Laughs]

She was, like: “We’re going to use the waste, and we’re going to make profit, and that’s what we’re going to use to reduce the waste in the end?” I said: “Exactly!” And it worked—and people got excited about it. You need technological and social impacts to create change. You need them both.

You need technological and social impacts to create change. You need them both.

Of course we also need to consider beauty. With your recent increased interest in biomimicry over the past few years, your glowing trees project combines natural luminescence with plants, which you suggest could eradicate the need for street lights. This could be a glimpse of a future where we are surrounded by—as you put it—energy neutral tools and artifacts. This suggests a world where technology is less screen based and more environmental, or experiential. It sounds incredible, but is it ambitious to think that today’s society will accept that we don’t need, or don’t want, screen based digital technology?

First of all, your initial comment is absolutely right! I think our desire for beauty—a natural desire for beauty, which everybody has, even the hardcore business people—is the real force that will hopefully save planet Earth from us human beings. [Laughs]

I believe it’s in our DNA. In the end, when we really, really, really, really have to make a decision, we’ll say: “OK, look. Maybe we shouldn’t make these ugly coal factories. Maybe we should just find a new way.”

The notion of beauty is really underestimated in a lot of discussions, even in a public forum. But I think it’s a true essence of being human. Beauty, in that way, is not decoration, but a very powerful tool, and a powerful dream to reform. So that’s one point.

Second: today, technology isn’t just jumping out of the screen. It’s on our bodies, our clothes, and what we wear. So yes, there will be screens. But we won’t be looking at them in the same way, or as much as we do now.

I don’t have any children, but if I did and they asked: “Daddy, daddy, what should I study?” First, I would say: “You figure it out for yourself. But if you really want me to give you advice, don’t study architecture. Don’t study design. Don’t even study technology. Study biology or biotechnology, learning from nature, and where can we implement that in a world of today.”

It’s not just about putting grass on roofs, or planting more trees. It’s really about understanding the core principles, for example an anthill, and then looking at ourselves and acknowledging: “Wow, we are a brutal people. Maybe we should find a better way.” So now my focus is mostly on that.

It’s difficult, because you need a lot of fundamental research. When I think about the cities of the future, that’s going to be incredibly important, where we’ll grow things rather than just build them.

Earlier, you mentioned wearing technology and I’m fascinated by your Intimacy Project. In the race to dominate wearable technology, we seem to be limited to watches and wristbands but you’ve developed a project where technology is built into the clothes themselves. It explores the relationship between emotions and technology, with the clothes becoming increasingly transparent based on close encounters with other people. With this in mind, what’s your view on the future of wearable technology?

It’s going to be interesting. First of all, it’s weird that most innovation in wearables is absolutely not happening in the fashion world. When you talk to the major fashion brands— Louis Vuitton, Dior, Gucci—they’re still in the era of the fax machine. It’s incredibly conservative—and boring—in that way. So that’s very disappointing.

Secondly, it happens mostly on the American West Coast. The tech industry is waking up and it becomes really powerful when it moves away from blinking LEDs, or just as an effect. For example, when it gets connected to health.

If I have a suit which measures my heartbeat, or how much vitamin A, B, or C I need at that moment, it becomes something that helps me filter information, which gives me a hint or advice about my body. I think that connection will be made in the near future. And it will be incredibly powerful.

You’ve also previously stated that your job as a visionary is to play with a problem, propose solutions, and to make people think. However, your critics might suggest that your projects, although stunning and compelling and incredibly aspirational, haven’t been scaled. In a previous conversation you and I had, you described your work as prototyping the future of cities. Is your intention to show the way forward, to provide a glimpse of a possible future, or to encourage others to take up your ideas? Or is it really about scaling your prototypes to fully realize global movements?

To be honest, it depends on the project. There is an increasing focus on intimacy; showing and hinting; and hacking and questioning; and that pushes the discussion, and other people can pick up that idea. They come into contact with that idea and then start doing their own thing with it.

With the Smart Highway or with the Smog Free Project these are absolutely meant to be scaled up—gigantically—to become part of the new standard. But as a young design studio—we’re only six or seven years old—it is difficult to achieve at the moment. That’s why we work together with the big industrial companies.

But we are definitely looking for that scaling, and not just for our ego or the money. We need to create impact, so that’s straight in the kitchen, as we say.

These projects should be more than just a symbol, or for promoting awareness. Even though that can be great, it’s not going to save our ass. We definitely need to do more, so I agree with the criticism.

On the flip side, your email signature includes a striking message: “I believe we should do more, not less, and make modern cities liveable again.” That seems to be your beacon, your mission in life.

Yes because I can be surrounded by people with opinions saying: “Do this or do that.” That’s all great, but I cannot do it alone. I’m tired of opinions. I want proposals. I also need to have leaders who can say: “OK, Daan, this is our problem. This is our budget. This is our question. This is our dream. Go!” And I also need the context to do it in.

How can we organize a system which is more proactive, which is more about capability rather than sitting behind and just giving commands—and needing to be right all the time! This is passive and won’t help us, at all. It needs to be social. It can’t be like my business developer’s initial reaction about the jewellry proposal. It needs to have a proactive mentality. This attitude and mentality is in our studio all the time.

To ensure we achieve it, we intern every senior person who comes to our studio. They get this mentality engraved in their brain. If they disagree, that’s fine. I don’t care if they’re the intern or a senior manager. If you save time and come up with a new proposal yourself, then you’re automatically part of the process—as a participant, not as an observer. That’s really important to make sure things are done and realized.

It reminds me of [Architecture For Humanity founder] Cameron Sinclair’s comment: “People don’t fund problems, they fund solutions.” This sounds similar for you: if you have an issue with something you’re proposing and you don’t agree with it, come back with a solution. Come back with something else. From what you’re saying, that’s ingrained in the culture of…

For sure, that’s part of the process in order to speed things up. Why am I traveling around the world like a mad guy? It’s because I need to have leaders, or people who take ownership and make that part of the solution instead of the problem. And I’m curious to watch that happen. And in the moment, I really feel it. I talk with them. I can connect with it. That’s when new projects start. Things like budget deadlines, etc, come later, but that initial approach is really important.

And we don’t always connect with others. For example, with the Smog Free Tower project I had many, many meetings, and nobody wanted to do it, or to spend time, money, or energy on it. The Smog Free Tower project was partly financed by our own studio—is partly financed—because nobody wanted to take the initiative. But now, it’s there. Now, everybody is calling us. So you need to take some risk for yourself, as well.

Commitment and risk!

With that in mind, no doubt many people would agree that your work epitomizes innovation. Of course, it has become fashionable in business and design circles to loosely throw around the word innovation but with little evidence to support those claims. My view is that innovation is a game-changer, not a tweak. In your opinion, what are the greatest impediments to true innovation?

Every good idea has a consequence. Every good dream can be redefined. A lot of innovation is, indeed, focused on one component to do a new thing—but in the old way. It’s like your Mom wants to be your Facebook friend. These days, a lot of so-called innovation is defined as doing the same thing but less bad, five percent less worse. For me, this is not innovation. It’s just damage control.

These days, a lot of so-called innovation is defined as doing the same thing but less bad, five percent less worse. For me, this is not innovation. It’s just damage control.

The true sense of innovation is redefining the purpose. Who you are, what you want and how are we going to do it? And having the guts to question that. That’s why I’m giving you the example of the underground parking places. You can make parking places even better than they already are and forget about the self-driving car, seeing it as an issue that pops up somewhere else. But it is hacking your business, it is hacking your existence—and you don’t even know about it, or choose not to care.

You need to have a 360 view and as a big corporation, you can do that with good leadership, by teaming up with smaller companies who are more flexible and faster, which speeds up the process.

Most of all, it is about having the curiosity, or just sheer desperation if it helps motivate innovation. I have those kinds of clients who are curious and who are incredibly desperate. I like them both—a lot.

I’ll finish on this question: What advice would you offer designers who are interested in changing the world for the better but aren’t aware of how to do so, or how to start, or how to achieve a small percentage of what you’ve done in a relatively short period of time?

I don’t know. Just start doing. Just because there is no door doesn’t mean there isn’t a key. You just start. You go out there. You get annoyed. You get amazed. You get obsessed. You get curious. You come up with proposals and make a prototype.

You think about: “Oh, who should I contact? With whom should I talk? Where should I position this idea to create maximum impact?” Just start talking about it to your friends, to your wife, to your boss, to your fellow colleague and sooner or later, somebody will plug in to that idea. It starts to grow.

Be amazed and drag that amazement into action. That’s innovation in a world where we are all more or less connected. I make things, but the making also makes you. There’s this interaction between you and world. You should embrace that—and help old lady’s on a Sunday evening. That’s also amazing.

[Both laughing.]

Image Credits:

All project images sourced on Studio Roosegaarde website: