Part one of a two-part interview, Damian Borchok invites us into a detailed discussion around the business of design and, in the process, reveals four specific business models that design companies often pursue.This interview was featured in Open Manifesto #7 which focused on the theme ‘Enlightened self-interest’.

Note: At the time of this interview, Damian Borchok was CEO of Interbrand Australia. He is now Managing Director, APAC, of Koto, Sydney.

Kevin Finn: To start with, you’ve publicly acknowledged that Interbrand has often been referred to as Inter Bland and you’ve responded by explaining the reason is that, historically, the network has primarily focused on strategy, but at the expense of creativity.

Damian Borchok: I think that, globally, the business recognizes that challenge. Over the last few years the business has been focusing more on elevating creativity. That started with the development of the manifesto around world changing brands, which has been something that’s unified the business over the past few years. It’s a very clear ambition that’s been stated at the most senior levels; it’s fundamentally important.

Generally, there was a recognition that business creativity is a growing requirement. Strategic services are valuable, and they’re not diminishing in any way. But certainly there also needs to be an ability to “operationalize” those strategies, to be able to show the proof of our advice, and in the way that we make those strategies visible. For us, this was a natural concept to follow; it’s certainly something that is incredibly important. Of course, the big challenge with any shift is: Do you have the talent? Do you have the will to make the decisions that are often difficult when you’re looking at changing the direction of any organization?

One of the really important aspects concerning the process of creativity is you have to be very conscious of creating the right conditions for creativity to happen. For any organization that is changing, that’s one of the most difficult things to achieve, because an organization is wired in one way to do something well. If it has to be wired in another way, to do something that’s different, it requires a lot of leadership, a lot of very clear thinking and commitment. It is critical to ask: What conditions are required? For creativity you need to have an environment where people are always finding sources of inspiration. They need to be living and breathing it. They need to be having conversations with other creative people. There needs to be a natural flow to that creativity, because it isn’t something you can necessarily schedule from 1:00am or 1:00pm or 2:00pm, and then expect something to pop out at the other end. It is a far more natural, organic activity. The consequence of this is that you need to be able to create an environment where this can be done effectively.

You also need to have established a very clear vocabulary within your business—a vocabulary for understanding the creativity you’re trying to achieve, and how you get to it. It becomes a language that allows you to elevate creativity. If you don’t have people that can have those sorts of conversations, whether they’re strategists, client service people, designers, writers, or leaders of the business, it’s very hard to innovate the nature of what their creativity is—and improve it.

That’s obviously another challenge that needs focus. And these are things we’re always conscious of. Even in our business, when we started that process, it’s essentially a never-ending watch.

There needs to be a natural flow to that creativity, because it isn’t something you can necessarily schedule from 1:00am or 1:00pm or 2:00pm, and then expect something to pop out at the other end. It is a far more natural, organic activity.

I guess an easy way to export this throughout the Interbrand network is through evidence—and there is evidence that you’ve achieved this, so it’s not something the network is trying to figure out. The question isn’t, “can it work?” because it’s working. But in your early days, and in the context of the Australian office within the global business, I believe you were quoted as saying, “If we’re so good, why are we so small?” Was that tough medicine for Interbrand to take?

The conversations around Interbrand’s creativity were actually held separate from what we were doing. Globally it was decided that it was important to make a change, and we came to the same conversation together. That’s how it emerged. It wasn’t really tough medicine, at least not from an Australian, or New Zealand point of view.

It wasn’t a conversation that we ever had with the global CEO. It was something that we talked about because it was an ambition for our business. But those conversations around the business—in relation to developing creativity—was certainly something that emanated out of a global decision and which came from our CEO. It was as you’ve described it.

Part of achieving this is attracting big talent. In previous conversations, you’ve indicated there may have been a difficulty to attract that big talent, because Interbrand wasn’t seen as a creative powerhouse, that it was seen more as a strategic powerhouse. How did you address this barrier, and what was the offer? What was the benefit for big talent to come on board?

It was a very organic process. As I’ve said, the previous incarnation of Interbrand was very much a strategic business, which had some creativity. But it was certainly not of the quality that I wanted or set the standard I expected. We needed to convince the marketplace this could change, whilst at the same time, we were only just turning the business around. There was very little evidence to demonstrate our ambitions in the marketplace, so it was probably about two years of hard work. It was very much conversation by conversation.

Internally we’d already set down the path that we weren’t going to tolerate anything but a substantial lift in the way we did our creative work, and that we were not going to rest on our laurels once we thought we’d done some good work. It was very much: “What’s next? How do we elevate what we do?” The challenge we essentially had was to present our credentials and our portfolio to every employee that potentially walked through the door, to prove to them that we were a business that was changing. It was very much a two-way conversation, rather than a one-way interview, which is often the case.

I guess we were lucky that we spent quite a bit of time with our talent consultants—who were looking for people for us—to first get candidates well calibrated in order to be able to have that first conversation, before we even met them. It was very much: “Look, when I’m ringing up someone I know you may have a perception about Interbrand, but please you need to see them. They are changing.”

We had some really great advocates in those partners. We still do. They’re all very good at being persistent where some people have questioned whether Interbrand was changing as a business. Once people met either myself, or our creative directors they saw that there was a genuine passion, which was supported by very clear evidence. And there wasn’t just a high degree of creativity, but strategic thinking and intellect as well, which we brought to the conversation.

Because we believed in ourselves, it provided candidates with a sense of belief. We were delivering the right outcome. And more people want to be part of that. From those little conversations we were able to build up a stronger team. Then, ultimately, our work became more public. As a consequence of that, it became more recognized for what people see it is today.

It’s tricky, because you really have to make hard choices early on…

Yeah, you do have to make hard choices. It requires a lot of intestinal fortitude. It requires you to be challenged about what you believe in—almost on a weekly basis. It needs to be crystal clear: “You know what? Here’s a culture that I like and I’ve got a really clear view about what they stand for. These are people I need to work with.” To me it is very much that kind of strength of character that I think we need to have more of in our industry.

You have a very interesting and novel way of looking at new business. You actually refer to it as an extreme sport. Can you expand on that?

That’s probably a reaction to my personal feeling about sport. I’m not particularly into sport, generally. I know that to get balance I need to find some activity that I can compete in. I just personally like business development. It’s a form of competition. For us, it is about the knowledge that—in our kind of business—we are project based and you only have so many opportunities in 12 months to win a piece of work. You have to be incredibly intense about that. There are way too many agencies. I know we get feedback from clients after we’ve won work, where client’s have said some of the other agencies had proposals which were full of mistakes. They clearly didn’t put the effort—the thinking—into it. There really wasn’t the commitment.

To me, it’s the opposite. You need to have the energy and the drive. You have to think about every opportunity. If you decide to go for that opportunity, then you have to put absolutely everything into it. Because you have to assume that your competitors are doing the same. You can’t ever sit on your laurels reminding yourself that you’ve had a good run of wins and therefore you have some magic formula. It’s never that easy. To me, that kind of intensity of thinking is required. If you miss that opportunity, you never get that back again. You’re losing a fairly substantial opportunity. And if you lose a couple of them, you find your pipeline is declining very quickly. You’ve got a business that’s going to be in strife.

You can’t ever sit on your laurels reminding yourself that you’ve had a good run of wins and therefore you have some magic formula. It’s never that easy. To me, that kind of intensity of thinking is required. If you miss that opportunity, you never get that back again. You’re losing a fairly substantial opportunity. And if you lose a couple of them, you find your pipeline is declining very quickly. You’ve got a business that’s going to be in strife.

Having a strong new business pipeline and having a strong capacity to win makes so many other problems in your business go away. You’re not chasing money. You’re able to hire more talent. You’re able to give people pay raises. You’re able to find two or three different skills to hire into the business that you didn’t have before. It facilitates so many different things. It allows you to sleep at night because you’re not to worrying about when the next dollar is coming through the door.

That’s why it is fundamentally important to the business. A lot of people find business development quite scary and intimidating. Whilst we believe it should be intense, it should also be fun. It should be an exhilarating activity where you can ask: “Can we trump ourselves?” So, we review how we’ve done a pitch and how we actually engage a client; do we see the excitement on their faces when we talk about their business? All of those things should be an energizing experience.

I imagine there is a lot of investment within that, too.

There is a great deal of investment, and that’s where the balance is really important. I’ve said previously we are very clear about what we choose to pitch on and what we won’t pitch on because pitching does take a lot of energy. It’s important to be able to choose the kind of work that you want to do, and choose the kind of opportunity to optimize that energy, and in turn to get the right work that you are best at doing.

The other side of this being like a sport is the fact that all of it can often be seen by people as a very stressful time and there is certainly intensity and stress around it. But I don’t think it should be. I’ve seen some organizations get very tense and uptight about the pitch process and so they play a very safe game. They try to second guess. They worry about: “How should we reduce our fee so that we win business?” All those kind of things simply degrade the work.

The quality of the pitch is very much around how do we energize; how do we show what the future of the business is and where its potential is; and how do we excite the client by having more fun; and do we actually enjoy the opportunity to engage a client that way? When we ask: “Should we expand on our part of the pitch?” I think that kind of energy rubs off, in terms of how the client feels about you and the kind of experience they’ll have.

If you look at the extreme side of sport, it’s pretty dynamic and risky. And in the case of business—and particularly in a pitch scenario—there is always a fear that the financial value, as seen by the client, is perhaps only visible through the implementation or the application of the pitched idea, rather than the idea itself being considered valuable. With this in mind, do you tend to look at pitch work as something that needs to be paid and valued, or is that incorporated into the fee if you are appointed?

Basically, we don’t get involved in creative pitches and very rarely do we have a situation where there is a fee type of situation. It is more a consultative type of engagement we have around a pitch. It’s typically more about us being able to demonstrate the way we can think about clients, and how we could potentially shape their business. It tends to be more around that. We focus very much on the idea of putting forth a strong point of view around a client’s business first. The reason for this is partly about selection. Now, some people think if you put a strong point of view on the table straight up to the client you could end up losing them.

Our view is that: “Yes. That’s correct,” but more importantly for us is that we need to truly believe there is a substantial problem to fix because we’re not there to just make the client happy, or that it’s just purely a meeting of minds. It’s about us as professionals, and experts in our area of branding, and applying those skills to a category, and saying, “Look. There is a lot broken in here that we think should be fixed. Are you up for it?”

There are some clients that say: “You just scared us. It seemed too overwhelming.” That’s fine, because we know that when you get into a relationship with a client it is an expectation in how you pitch and how you win, and then it becomes something else. But that’s a dishonest relationship. For us, we want to win work by clients who are inspired and excited by our perspective and occasionally say: “You know what? We had a view about this, and these guys have been taking it to another level, or they’ve slightly reframed the way we thought about things. We really appreciate that kind of input. That’s the kind of professional relationship we are looking for.”

In some ways, the pitch process becomes self selecting. You get clients that you want to have, and clients that you deserve. And you get the projects you deserve, rather than just picking more work in order to get more revenue because at the end of the day what you usually find is you have a disappointed team, a frustrated team, and ultimately they’re stuck on a project like that for six, 12, 18 months. Often they want to go somewhere else and work on another project. They don’t want to be there. I don’t believe that you should be winning work under false pretences.

A client shouldn’t be appointing you under false pretences, either. That’s why the idea of the strong point of view is an incredibly important part of the conversations that we have, and hopefully through those conversations and engagements they see the value in what we do.

The pitch process becomes self selecting. You get clients that you want to have, and clients that you deserve. And you get the projects you deserve, rather than just picking more work in order to get more revenue.

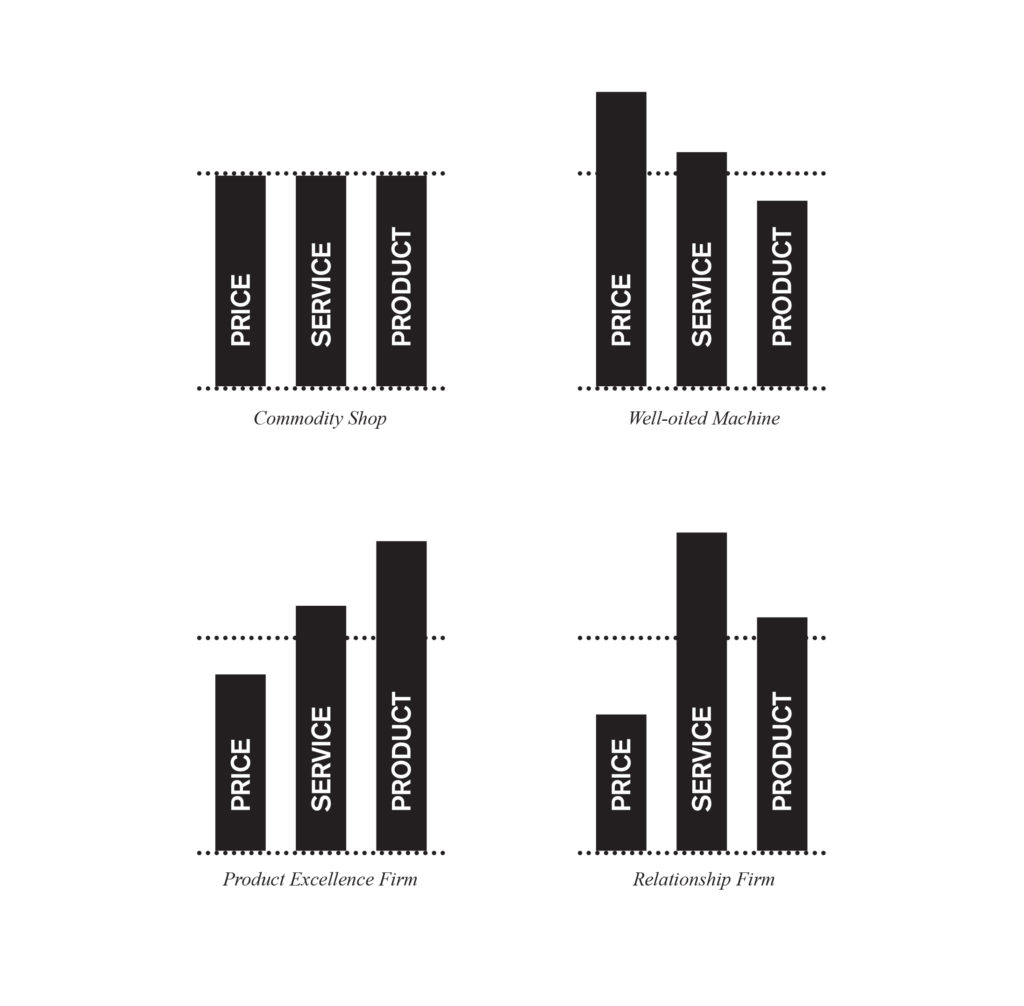

That fits with your view of the four broad business models you’ve spoken about, and which you believe designers tend to fall into. Your view is there is generally some sort of trade-off within those models, which include:

1) Commodity shop.

2) Well-oiled machine.

3) Product excellence firm.

4) Relationship firm.

Can you briefly expand on these and discuss which business model Interbrand adopts, based on the pitch model you just described?

Sure. The commodity shop is the one that I feel way too many businesses in our industry operate within. That’s why there’s so much conversation around: “The clients are pushing our fees down. It’s really hard to make money.” This is always a struggle for our industry. That model is based around trying to balance a whole range of things rather than having a strategic discipline and deciding: “You know what? We’re going to be good at one thing.”

Frances Frei lectured at a Harvard Business School, that I took. She talks about the idea of excellence. Part of her theory on excellence has been that great firms give up something. They are always going to be good at this and bad at that, because there are only limited resources you can apply. It’s just not possible to be great at everything.

Similarly, take a company like Apple. If you’ve ever heard one of Steve Jobs’ rare interviews, he states: “We’re a product firm. We’re a product firm. We’re a product firm.” That’s his message. You see that in so many of the decisions they make. For me, the strategic clarity of this message is important. You’ll never get out of the mire of being a commodity shop unless you make those trade-offs.

The other three are potential broad models. And of course, there may be other models. Certainly, the well-oiled machine is the company that says: “You know what? We want to be a high volume business. We know to do this and to make a wide market name we need to be low margin.”

But there’s a consequence: “We need to make some trade-offs. We can’t attract talent because we can’t pay top dollar for them. And because we need to turn things around quickly, we may have a higher staff turnover.” The consequence of that model is they make the choice and—in all likelihood— the product quality isn’t as high. Not surprisingly, the client doesn’t really look through the lens of quality in the same way a client who pays top dollar for design.

In fact, most of the product quality is likely to be traded off heavily. Service may need to be a little bit better to be able to smooth out some of those challenges of being a good low cost provider. That’s one option.

The second one is very much the service… and that’s rare. This is a firm that’s actually committed to long standing client relationships. Year in and year out, they have a reasonable understanding of what kind of budgets they’re going to get from clients. They’re very well connected at keeping a matrix structure of relationships with the business. They have good long standing connections.

The consequence of this model is that the relationship becomes the primary choice maker for that organization. They’ve probably made a decision to be as good as possible by having a good relationship with a client. Difficult situations can be overcome by having relationships and this also gets you on the ground for picking up pieces of work.

The challenge lies in the nature of the work that we do. You are often dealing with quite prickly situations when you’re having conversations about activity, quality of work, strategy and things like that. At some point in the relationship there’s always going to be tension. Some of them can be quite scary.

Organizations that are culturally focused around relationships find those kind of tensions quite difficult to deal with, particularly if they see it as a threat to their relationship and where they’d rather remove that friction.

As an organization, what they’ll often do is make a trade-off between product quality by saying: “The client’s not happy, we’ll make them happy.” They’ll trade off the quality of the work or they will try to mitigate risk. Doing work which is too edgy, or too radical may upset the sensibility of the client. As a consequence, they make that trade-off. Typically, that sort of organization can charge larger margins because they have that strength of relationship, particularly at higher levels. They can negotiate their position very well.

The other strength to their business is a higher degree of certainty regarding work and revenue. As a consequence, they’re probably better at negotiating longer term relationships and achieving efficiencies in how they run their business simply due to that degree of certainty.

We see our business as a product business. The reason for this is we very much recognize that in the world of branding there is a lot of innovation to be done. There is a lot of development around how you use brands. And there is still a lot of uncertainty among many clients about the value that it creates.

For us, our ambition is very much based around that. Our focus is around how we show that brand isn’t simply something that you stick on the top corner of the website, or on a business card, that it’s really a time situation, that it’s actually something that operates at a holistic, operational level. It is the interaction of all the touch points of your business that help drives value for your brand. As a consequence of having that view, we know that we are having a combination of educational style conversations and learning type conversations.

We have difficult conversations about why maybe some people within a closed business have a negative perception of brand—or a very out-dated view of how brand works. It often means we have to be up front about having those difficult conversations. We’re also very conscious that most categories get into a rut, in terms of how they represent their brands. Give them a few years, and they all start copying each other. Everybody starts looking like one another. Even behaving like one another. They all follow the same rules. Part of our job is to break that. To break those conventions; it’s one of the key tension points.

For us, it’s about asking how we create the conditions where a client can come on that journey, to understand why it is better to break from the pack than to be part of the pack. That requires a fairly innovative conversation, and discussions about the way you think about how brand works.

Often we have conversations about the branding textbooks. Our feeling is that you need to be careful of what you read because clients often have the impression they have to retain things they’ve held for a long time. That’s the way that they interpret it. We often have to show this isn’t the case. The concept of brand equity dilution hasn’t been talked about enough. The fact is markets change and shift, and consumers change and shift, and technology is only accelerating this.

The stuff that clients thought was an equity for them, and was valuable a couple of years ago, has now become something that is largely diluted in terms of value, in terms of changing and shaping behaviour. Typically, the marketplace is ahead of that. Having those conversations is often quite challenging.

For us you can’t have those conversations if you’re a service type firm. For us, we need to be saying: “We are committed to the improvement and innovation of brand. As a consequence we need to focus on the product,” which is the kind of stuff that we provide our clients.

The concept of brand equity dilution hasn’t been talked about enough. The fact is markets change and shift, and consumers change and shift, and technology is only accelerating this.

You mentioned earlier that clients tend to find it difficult to understand the value of brand. Economists do as well. The whole financial industry can’t put a tangible value on brand. Those conversations you have with your clients, surely they have to be backed up with some sort of evidence, or proof, or some logical common sense reasoning?

That’s where I’m constantly looking and we have a bit of an advantage in that, because we [Interbrand] value brands at a global level. We have lots of debates about: “What makes brands successful?” We can use this to support our arguments. And we have an analytics practice in the business, as well, where we are required to model different solutions. The way we approach it isn’t running the typical focus group, or the traditional feedback targeting, because to me those are probably the most redundant, outmoded ways of looking at consumer behaviour.

We rely very heavily on case studies about brands that are doing really emergent work, and which are successful. There’s way too much focus on well established and mature brands who have a set pattern around what they do. They’re not likely to change very much, simply because of their scale and ability to apply change capably. Their success comes from that—it’s not necessarily a branding innovation that is driving their ultimate business success.

We try to look at the brands that are emerging and which are doing interesting things. We ask what that means to the future of brand. We often bring those kinds of conversations to clients. For us when you’re engaging a firm like Interbrand, or any other branding or design firm, what you are doing is asking them to help you to innovate your brand.

To simply say: “We are just going to polish the brand and put it back on the mantel place,” isn’t really something that’s useful. That’s a cleaner’s job, not actually a branding firm’s job. For us, we want to look at where things are changing. We build to bring your brand to your future—not to your past or your present.

From personal experience I often encounter clients asking to be re-branded, when essentially they’re really looking for an identity refresh. One of the greatest definitions I’ve read between identity versus brand is from Ian Anderson [Designers Republic]. He once wrote that: “Identity is how you look. Brand is who you are.” They’re two totally different conversations. Do you find that clients get that distinction, or is that part of the education process?

That is very much depending on the clients that you meet. I would still say that many, many clients—probably the majority of them—still look at the identity refresh. Those clients have managed to get some extra money within that year’s budget. They haven’t looked at their identity for a few years and feel it needs tidying up. The argument has been made at a fairly rudimentary level to get that additional operating expenditure, to possibly get a capex to implement. Really there aren’t enough conversations yet about the what versus the who. That’s partly the evolution of the Australian business landscape. It needs to focus on more advanced thinking, particularly if it wants to be competitive against the world’s best.

That is the challenge, because there are more and more smart organizations with very progressive CEOs who are saying: “You know what? This brand thing, lets put all of our focus on getting our business turned around, about how we operationalize the way we deliver services and products, and then line up brand with this and discipline the business about what we’re all about.”

What we have there is not simply the brand team communicating stuff to the market about how grand they are, with the rest of the business disconnected from this and any success is really just serendipitous. Instead, what you have is an organisation that’s structured to consciously use all of the elements within its portfolio to be successful. What you’re doing is implementing the delivery mechanism for the promises your brand makes. It’s your identity and business model working in concert—and you end up with the proper value creation model working.

What you have is an organisation that’s structured to consciously use all of the elements within its portfolio to be successful. What you’re doing is implementing the delivery mechanism for the promises your brand makes. It’s your identity and business model working in concert—and you end up with the proper value creation model working.

I think a lot of creatives, in particular, feel that business is dry and dull, and probably well out of their skill set. Most creatives haven’t been trained in business. One of the interesting things about your situation, as CEO, is that you have a very fluid relationship with your Creative Director. So much so, you can influence the direction of a creative project just by being a part of that process. That’s probably critical to collaboration and the success of what you’re talking about. However, some might suggest this could be dictatorial. Should a CEO undermine a Creative Director and creative decisions?

Yes, I could see if I was undermining the Creative Director that would be dictatorial. That’s certainly not the relationship that we have. Essentially, our Creative Directors have a real passion around our clients and the business. And this fluidness cuts both ways. We don’t necessarily see there’s a demarcation. You need to know the people who have particular skills, and respect them. In day-to-day work life, I’m more than happy for strategists to bleed over into creative, for creatives to bleed over into strategy. For a Creative Director to come to an interview with a CEO is key to understanding how their business ticks.

It’s the accumulation of all of those interactions that provides far richer material. To understand that this brand thing isn’t something that’s detached from the business. The business and brand are interrelated in their ability to be able to be successful. I advocate identifying a combination of things that go on in business. I have a real passion for how business can transform and be better. I also have dismay in how often conservative—to our detriment—they can be, and how misguided, in terms of how brand is used. For me, those are the kind of energies that partly drive the business.

The business and brand are interrelated in their ability to be able to be successful.

At the same time, I got into this industry, not because of that, but because I had a passion for design. I’ve spent my career trying to understand all sorts of design. I have a breadth of understanding of architecture, industrial design, and graphic design. Not only with regard to what’s happening now but from an historical perspective, because it’s something I have a real need to know.

Being able to do that, and being able to help facilitate other people to broaden their view of how those interactions can actually create better results—this is important to me. That’s more the intent of what we’re doing. I think our business is certainly heading more that way. And of course, there will be more blurred lines between all the different roles in our business. Our work changes when those crossovers happen and it becomes more interesting and more creative. I only see upside in that kind of relationship with different people.

I know of instances where CEOs became involved in the creative work and completely made a mess of things, and that’s where the autocratic approach is problematic; particularly if you’re a CEO that doesn’t have a particularly good understanding of the creative process. The way that we work is quite different to that. I’m not going to suggest there aren’t times when I say “No. That work is not good enough. We’re not taking that to the client.” That’s usually in the early stages of work. We usually go through a process. We talk internally about killing ideas fast, because we need to get to the right kind of answers very quickly.

Certainly, each person that’s involved in the process is there for a particular reason. Our approach is that a Creative Director can just as easily challenge the strategy work as much a strategist, or myself, can challenge the creative work. The key thing is that you first develop a vocabulary for what you are talking about. There isn’t much point to having a pure finance background if I’m talking about creativity, because I probably don’t have any understanding of the language around it. But I’ve spent a lot of time studying a number of different creative industries. I’ve obviously worked in this industry a long time. I have a vocabulary for the kind of work that we do, and particularly my interest is around how different creative industries innovate and change—and what’s leading edge.

I’m really keen to see that we bring those influences into our work just like our Creative Directors do on their side of the equation. Our conversations are highly collaborative. There are certain areas regarding the technique of what they do—whether it’s layout, whether it’s typography—that I am just completely out of my comfort zone altogether, and that’s where they are extraordinary. Then there are other things, when it comes to how we link the brand and the communication with the strategy, asking how you operationalise this in the business. Because the other side of me is very much around how businesses tick.

That amounts to what I bring. It’s very much around being able to bring a group of people together to have conversations about making stuff work better. In our creative process, I would probably say the first few briefs of developing a concept are almost entirely conversational. There’s almost nothing visual about it. The guys, just by nature of their work process, tend to talk their way into a solution. If they can talk about it for hours on end, and see where the potential is, they know that they can very quickly establish the visual structure for that. Once they can talk it, and convert that into a system, once they understand what that system is, it can then be tested through application—prototypes. And if it works well, that becomes the final direction.

You mentioned you went out of your way to study and understand creative language, the creative process, which is obviously hugely beneficial for the relationship you have with your team. And this is obviously in your own self-interest. So is it also incumbent on the designers to understand the language of business, because generally speaking, designers tend to dislike the idea of business? In my experience, it’s in a designer’s best interest—and self-interest—to understand business, regardless of whether they run or own a design practice. Is that something you require from your team or that you would even recommend, or suggest?

We don’t expect our designers to do MBAs or anything, but I think any designer who is serious about changing organisations must have a curiosity about their client’s business. It doesn’t matter if it’s a naive passion for it, but it’s fundamentally important. I know that, for example, one of our Creative Directors absolutely loves having a chat with the CEO of a business. He asked all sorts of questions like: “Why are things this way, and how does that work, and why would you do it that way? Show me why you’ve thought about this.” He has a very disarming way of having that kind of conversation. But when it comes to presenting the concept he’s got that conversation in his head, with that level of detail about how the business works.

We don’t expect our designers to do MBAs or anything, but I think any designer who is serious about changing organisations must have a curiosity about their client’s business.

And you can see it’s been woven from the decision making about how a concept solution works. That makes for a fairly powerful conversation, because they are talking about how this works for your business, rather than engineering a concept. It provides a much stronger foundation to clients for believing in the solution, and if you’re willing to present a more dramatic or challenging solution to the client it offsets some of the tension or nervousness about risk.

By the time you are at Creative Director level if you are not prepared to have those kinds of conversations with a client—simply believing the brief should have all you need, and your creative genius will save the day—you’re out of touch. That kind of Creative Director is so old school, and we never want to have one like that, because businesses are so complex, and the issues that you are dealing with, if you are seriously looking deeply into the brand of a client, you really need to have your sleeves rolled up. Otherwise, you’re not going to deliver a solution that has any sustainable advantage for them.

Nor will you be speaking a similar language.

Yes. You’re talking design language, and the client will end up asking someone to translate that for them. Our Creative Director talks a lot about having a mathematical logic so the client can see how you’ve come to your solution, because we know most organisations tend to be less brand orientated. You need to be quite sequential in your thinking; even though your creative process might have been more systemic. You need to then lay out your answer in a way that they will be able to lead effectively.

It also paves the way for intuition, because it is supported by logical, business-oriented thinking. You’re not just relying purely on intuition: “This works. Trust me.” And when intuition is introduced, this process has paved the way in the client’s mind where they are more open to intuitive decisions, because it is backed up and supported by other decisions that are much more logical, much clearer, and communicated in a way that is common business language. Would that be correct?

That’s right. And with this they should be able to ask advice. We typically look at the problem from an evolutionary point of view and explore how to then synthesize the solution, and I believe that is an incredibly important combination. I think being purely analytical gives you very dull solutions, and being purely focused on the simplicity of something without any connection to the real world you end up inside a very strange place where your success is often serendipitous. You might have a meeting of minds with the client, but it’s not necessarily connected to any substance. It is very much the combination of those components working together that get you the right outcome for the client.

I guess it’s seen as a grey area in the client’s mind because they are expecting to navigate a designer’s intuition, and that’s probably a frightening situation for many people who are embedded in the business world.

Yes. There are so many designers but when we have conversations with them there are so few we would hire, because when you ask them how they came to their solution they can’t give you an answer. They can’t articulate the process. There is another thing that many designers talk about: their work should speak for itself. To me, that’s an abdication of their responsibility, and an easy way to avoid providing a clear answer for their rationale.

There is another thing that many designers talk about: their work should speak for itself. To me, that’s an abdication of their responsibility, and an easy way to avoid providing a clear answer for their rationale.

The problem is they have no discipline around developing an idea first. That’s why I said earlier that our Creative Directors will talk about the solution from day-to-day-to-day, until they get to that point, because what they are doing is essentially disciplining their mind around an idea.

For me, I don’t like clients being annoyed and cynical if they need to decode a concept or figure out how you arrived at the solution, what the reasons are and why the elements are put where they are. If you don’t have a story that is supported by a logic I don’t think you have a solution of any substance. I know people often say: “it’s a systematic process that you don’t understand,” but that is a cheap way out. I don’t really buy that.